Scores of people visit Ivy Creek Natural Area, a nature preserve in Albemarle County, known for its amazing hiking trails. However, only a few people are aware of the site’s history. Long before it became a popular hiking destination and a protected area, it was a Black-owned farm.

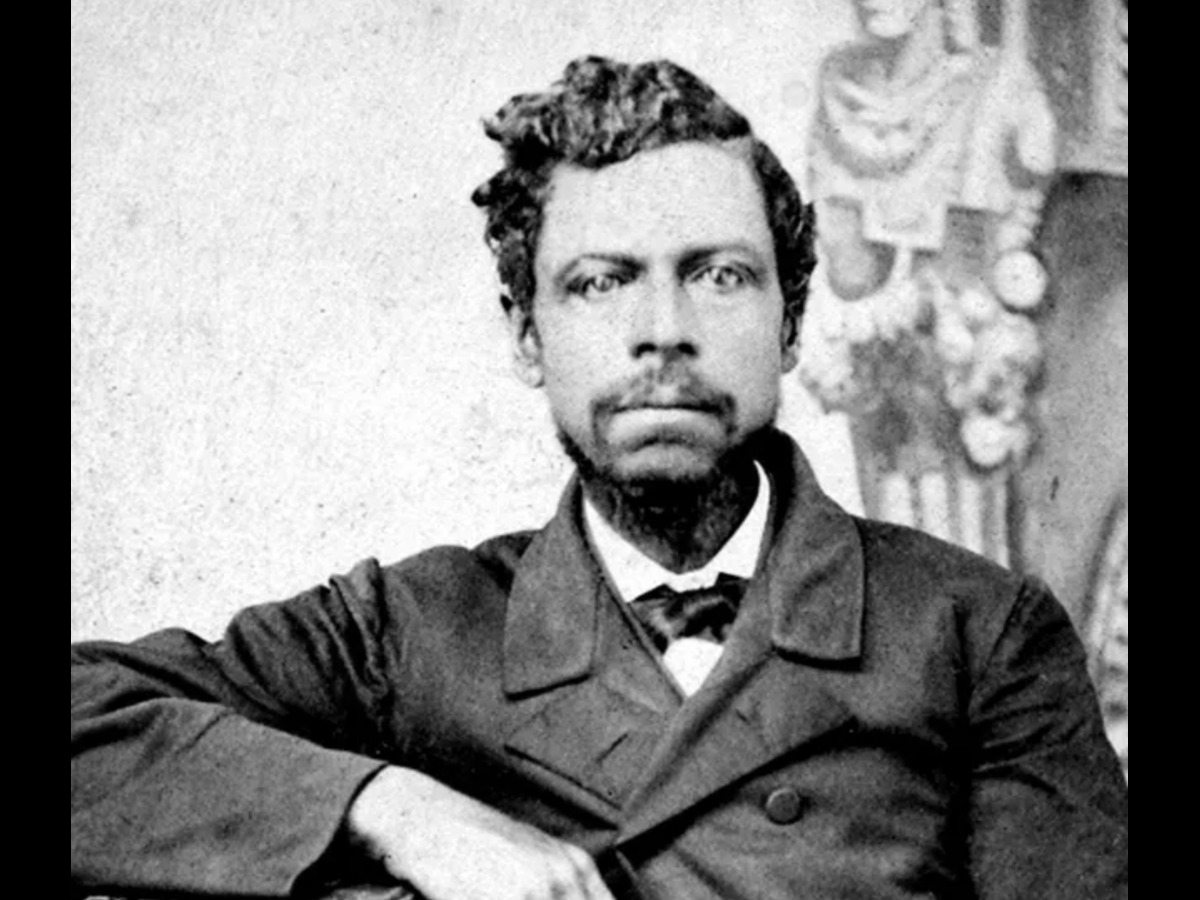

The historic River View Farm, located in the Ivy Creek Natural Area, is land once purchased by a formerly enslaved man known as Hugh Carr, who came to be behind one of the largest Black-owned farms in Albemarle County.

River View Farm was part of a thriving Black community known as Hydraulic Mills and Union Ridge. There were Black landowners, Black churhces and Black schools in the area whose members were building their lives after emancipation, a report by WVIR said. Carr’s family was at the center of that community, the report added.

“They [Carr family] were teachers. They were church leaders. They were agricultural educators,” Chloe Fridley, Director of Education for the Ivy Creek Foundation, said to WVIR.

Born to Thomas and Fannie Carr at the Woodlands Plantation under slavery around 1840, Carr became one of the many African Americans searching for better opportunities after the Civil War. Following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862 that freed slaves, African Americans were optimistic that there would be land reform that would pave the way for them to own land at last.

This did not come to pass. Thus, Carr, like many other newly emancipated African Americans, became a sharecropper, earning a small share of the crops, like corn, wheat, and tobacco, in exchange for his labor, as stated by history.

He later became a farm manager for his former enslaver at the Woodlands Plantation. This work helped him save enough money, and in 1870, he began to buy property near Ivy Creek. Carr acquired the land through multiple purchases, and eventually, he came to own about 125 acres of land, making him one of the largest African-American landowners in Albemarle County in the 1890s.

This achievement was rare, as many other African Americans could not easily obtain land. Since Carr could not read or write, he signed the property deeds with an “X.” In 1880, Carr built a two-story house where he and his family would live.

Carr and his wife, Texie Mae Hawkins, had their first child, Mary Louise Carr, in 1884, a year after they got married. They had six more children, all of whom attended schools in the community with their sister Mary Louise Carr. Many of the children became teachers and community leaders thanks to the education they received after being urged on by their father to take their studies seriously.

“His children went on to go to college. His grandchildren went on to go to graduate school. I mean, it’s just an amazing story of perseverance,” Fridley said.

Even when Mary Louise Carr had to take over her mother’s duties at home following her mother’s death at just 34, she still found time to attend Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute (now Virginia State University) in Petersburg, where she met her future husband, Conly Greer.

Mary Louise Carr went on to become a lifelong educator.

“His oldest daughter, Mary Carr Greer, and we have a local elementary school named after her,” said Kathy Mallory-Orr, Youth Programs Education Director with the Ivy Creek Foundation.

Greer Elementary School was named after Mary Louise Carr to honor a Black woman born on a farm and whose life story would shape generations of students.

Even after knowing that her father was enslaved, Mary Louise Carr, a humble soul, maintained a “cordial type of relationship” with descendants of the family who once enslaved him, Mallory-Orr said.

Today, Hugh Carr, his wife, his daughter, and other family members are buried on the land they fought to maintain for more than 100 years amid segregation and through different political times.

In 2020, River View Farm was added to the National Register of Historic Places for its historical importance in American history.