His images continue to shape everyone’s memory of the civil rights movement.

At every pivotal moment of the civil rights struggle, Ernest Withers was there. During the trial of Emmett Till’s murder, he captured the moment Moses Wright pinpointed one of Till’s killers, despite a judge’s no-cameras order.

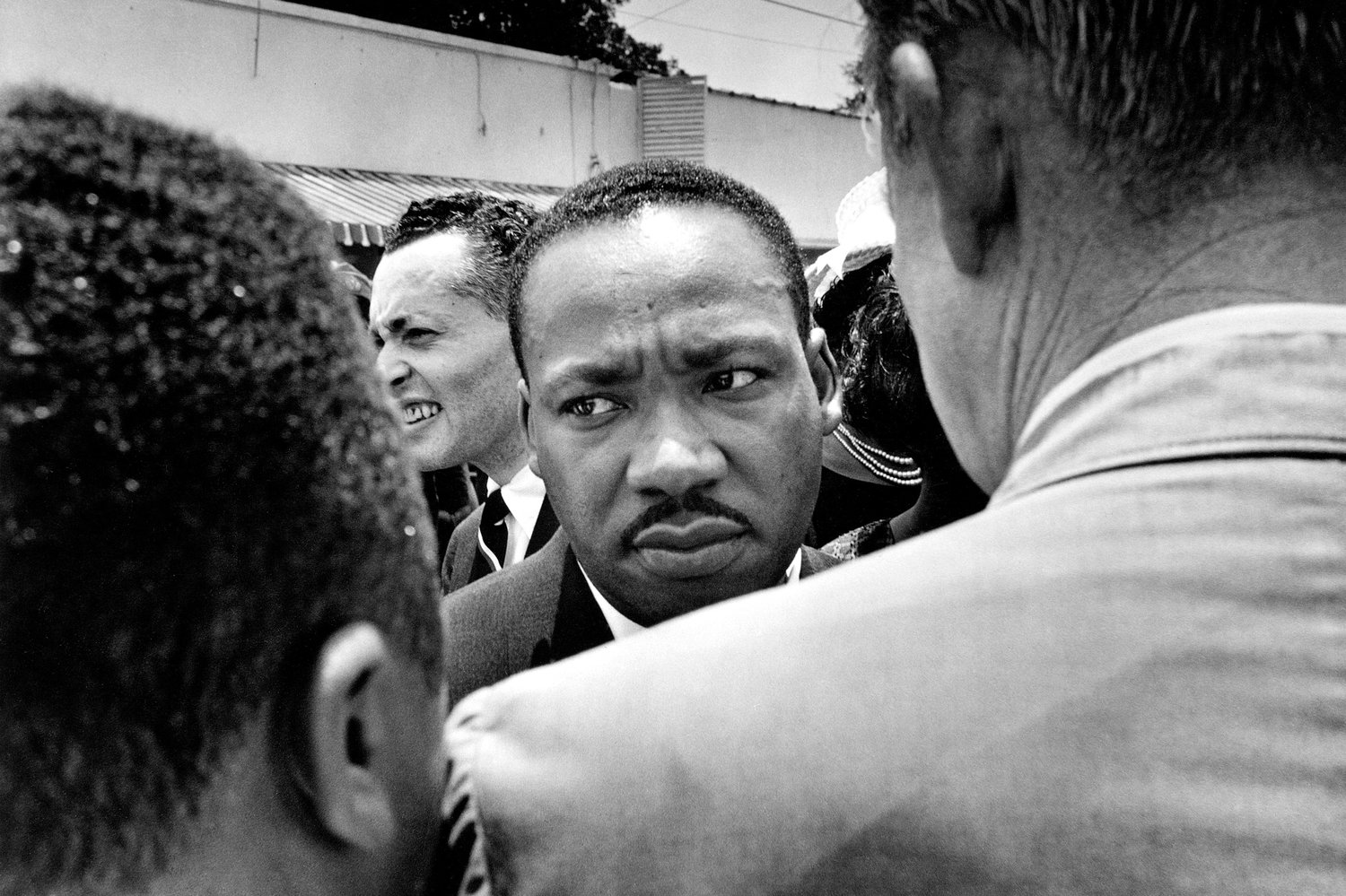

Often at the side of Martin Luther King, Jr., Withers also photographed moments the civil rights leader rode newly desegregated buses. Even when he was assassinated, Withers photographed him in the morgue.

Documenting every action, the famous black photographer further captioned the Freedom Rides, the funeral of Medgar Evers, as well as the heydays of Elvis Presley.

But three years after the death of Withers, it turned out that he was doing more than recording history – he was a paid informant for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

This was revealed in 2010 by the Commercial Appeal newspaper in Memphis, which reported that Withers “passed on photographs to the FBI along with names and background information about activists and details of schedules.”

The newspaper acquired these from records released under a freedom of information request, causing many to wonder why a black photographer would spy on a black freedom movement.

Growing up in the segregated North Memphis neighborhood, Withers served in the Pacific theatre during World War II before joining the first group of black police officers in Memphis. But he lost his job in 1948 and switched to photography which had been his passion.

Photographing black life in Memphis, reports by The Washington Post said his “black skin” and “easy smile” got him into the inner circles of civil rights leaders. Black civil rights leaders, including King, trusted him to the extent that he was often allowed to be present during strategy meetings.

“By the 1960s, Withers was relaying to the agency photographs and gossip about the Nation of Islam in Memphis, voting rights battles in rural Fayette and Haywood counties, antiwar hippies, and nonviolent ministers such as the Rev. James Lawson. He monitored the swirl of activists and politicians coming through Memphis, a crossroads city in the black freedom struggle. In 1967 he earned the designation of confidential informant on racial matters,” writes The Washington Post.

What is more, he spied on Catholic priests who supported a Memphis-wide strike by sanitation workers while recording car number plates of political activists for the FBI.

He also helped the FBI to disorganize the Invaders, a local black power organization with a large following in Memphis in the 1960s.

“He was the perfect source for them.”

“He could go everywhere with a perfect, obvious professional purpose,” historian David Garrow told the Commercial Appeal.

The FBI had begun monitoring King in 1955 during his involvement with the Montgomery bus boycott. Its director at the time, J. Edgar Hoover, was “personally hostile” toward King, as he believed that the civil rights leader was influenced by Communists. Thus, Hoover and his bureau started a series of covert operations against King during the 1960s.

Withers supplied intelligence to the bureau until 1975, having made more than $20,000.

He may have betrayed those who trusted him but reports said he probably agreed to become a spy due to the money involved. He could have also wanted to go back into the police force or he might have disagreed with the “street-theater confrontations of the civil rights movement.”

Whatever the reasons, Wither’s son argues that the revelations of his father’s involvement with the FBI did not in any way “diminish’ the impact of his work on the civil rights struggle.

“He had been harassed, beaten, shot at. He was a victim,” Rome said. “At that time, when you are the only black on the scene, you’re in an intimidating state,” he told the Commercial Appeal.