Secret societies, by their nature, breed curiosity. Often, the gap is filled with the most chill-inducing content that is sellable yet farthest from the truth it is intended to represent.

Secret societies do not often tell their own stories; their mouthpieces are usually others. The Abakua in Cuba is no different but it seems there are fears as to what would endure if the society’s image is not defended.

Writing for HavanaTimes.org, Jorge Milanes Despaigne noted: “Some young people have come to believe that being a member of the Abakua society is synonymous with strength, masculinity and manliness; and they evince negative attitudes based on false, racist stories that disparage and discredit this syncretic cultural tradition, one that has made important contributions to Cuban identity.”

So what or who is the Abakua? They are an Afro-Cuban fraternal society dating back to the 19th-century that keeps its membership and rites away from public eyes.

The Abakua say theirs is a mutual aid society founded by slaves against the backdrop of the vicious realities of slavery and colonisation. The inspiration for Abakua, however, was fetched thousands of miles in Nigeria.

The Spanish Caribbean was a hotbed depository for slaves from West Africa. Jane Landers writes in “Slavery in the Spanish Caribbean and the Failure of Abolition” that even in the 19th Century, years after the Spanish crown had outlawed the slave trade, Cuba’s economy was benefitting from the addition of new slave labour.

With the coming of new young men and women forced to inhumane servitude came different ways of life. Enslaved Africans tried to cope with the harshness of their condition by recreating the life they had known.

What arose was syncretisms of religious or religion-like groups in Latin and Central America. This should come as little surprise to Africans who know the esoteric and occultic interests of some diasporic Africans who visit the continent.

The Smithsonian identifies modern-day Cuba as a location for a “mystical subculture…formed during its years as a Spanish colony and plantation economy, when West African slaves melded their pantheistic worship of spirits with features of Catholicism”.

But the Abakua stand out from these syncretic mystical groups mainly because it is one of the few realisations of African slaves that was not formed with input from Catholicism.

Abakua is a rendition of the Ekpe or Ngbe cult, indigenous to the peoples of the Cross River region in modern Nigeria. The present capital of Cross River, Calabar, was in those times, a point of sales for sails that would go off to the New World with lower decks full of human cargo.

The Ekpe cult of Efiks was then recreated by the relatives who had been separated and shipped off. The cult is a secret society whose spirit animal is a leopard.

The Ekpe is hierarchical, with about seven or nine stages of possible graduation to the pinnacle. It is also open to only males.

The Ekpe itself is thought to be a spirit that roams the wilderness. Its powers have the capacity to create boom or bust depending on adherents carrying out supplications and paying tributes.

Although they are now a largely ceremonial group in Nigeria, the Ekpe cult enforced social and political order through physical and spiritually-inclined activities.

For instance, they had the powers to arrest, detain and try suspected lawbreakers. They also had public occasions where their members disguised themselves in significantly frightening masquerades.

The group’s cultic activities were kept strictly among members. It is believed they sought “esoteric teachings regarding human life as a cyclic process of regeneration including eventual reincarnation”.

Some even believed they could metamorphose into their totem, the leopard.

The name by which they are known now, Abakua, is a corruption of Abakpa, the place in Nigeria that the earliest cult slaves were thought to have come from.

The identification of slaves by where they came from was a common practice in Portuguese and Spanish colonies. Perhaps, this is why the Abakua had to be a mutual aid group instead of just a vigilante spiritualist cult. Bonding with people who have come far away with you is necessary for survival.

The Tabom people of Brazil are an example of this survival tactic.

Having come from Abakpa and Calabar, these Ekpe cultists were called Carabali Apapa Abacua.

When it made its way to the New World, the cult became a point to keep in touch with home and for one to never lose their way. However, the Ekpe cult also became an underground network of anti-colonial fighters.

Arts and culture curators, Lameca.org, point out that “the earliest references to Abakuá activity emerged in the 1812 Aponte ‘Conspiracy’, the first anti-colonial and abolitionist movement in Cuba, organized in Havana by Lucumí descendant José Antonio Aponte.”

It is also recorded history that in 1836, Regla in Havana was home to an Abakua cult or lodge. From there, it spread to other colonies, going as far as modern-day Florida.

Currently, there are thought to be over 20,000 members of the Abakua in Cuban cities such as Havana and Matanzas.

The group’s members retain the mystic and spiritualism upon which the Abakua was founded. Initiation rites still involve activities shrouded in deep secrecy.

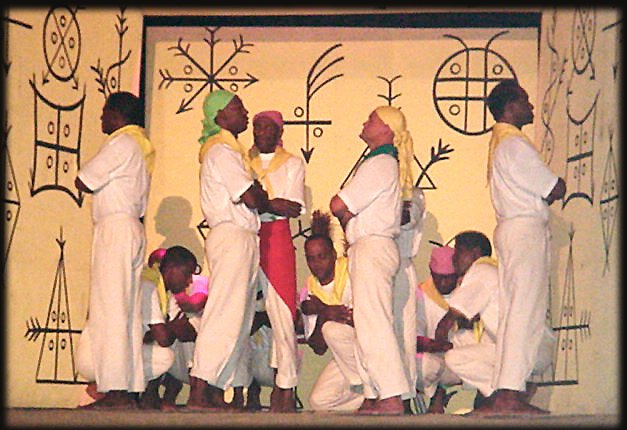

On occasions such as The Day of the Three Kings, members come out to make merry clad in masquerades, a homage to its Nigerian foundations.

However, in modern times, Abakua members can be identified by their tattoos too.

And perhaps as a result of its black African heritage, the Abakua are associated with criminality and communal hostilities. Some of its younger members are thought to be violent troublemakers.

These days too, Abakua is in itself a kind of music and dance popular in Cuba. This evolved as part of the adaptation attempts by the slaves to make their faith constituent in their lives in the New World.

Despaigne, who wrote his musings on the Abakua in 2015, wondered what the future held, after citing the volatile indulgences of some of its members: “The [Abakua] society has evolved and is a constant subject of study for multidisciplinary groups, owing to the fact that, in the past, complex gender and race considerations were applied to membership. Today, however, no society can remain secret.”