Born September 10, 1779, on the island of St. Kitts in the Caribbean to a wealthy merchant plantation owner called William Wells, Nathaniel Wells did not fully live out his life like other slaves in his day did.

His mother, known only as Juggy, was one of Wells’ lovers. After his wife died shortly following their arrival in the West Indies, William Wells is recorded to have had several relationships with some of his slaves, although he never married any of them.

According to records, William Wells accorded the slaves he had relationships with, as well as their children, certain favours. Of the about six children he had with various women, Nathaniel was the oldest.

In 1783, William Wells is recorded to have granted freedom to his son, later sending him away to school in England, hoping that he might attend the Oxford University but Nathaniel did not live that dream of his father.

Upon the death of his father, Nathaniel inherited his lands and property, including the slaves, and chose not to attend university at all. In 1803, he moved to Bath, England and later purchased a plot of land (2,200 acres) near Chepstow.

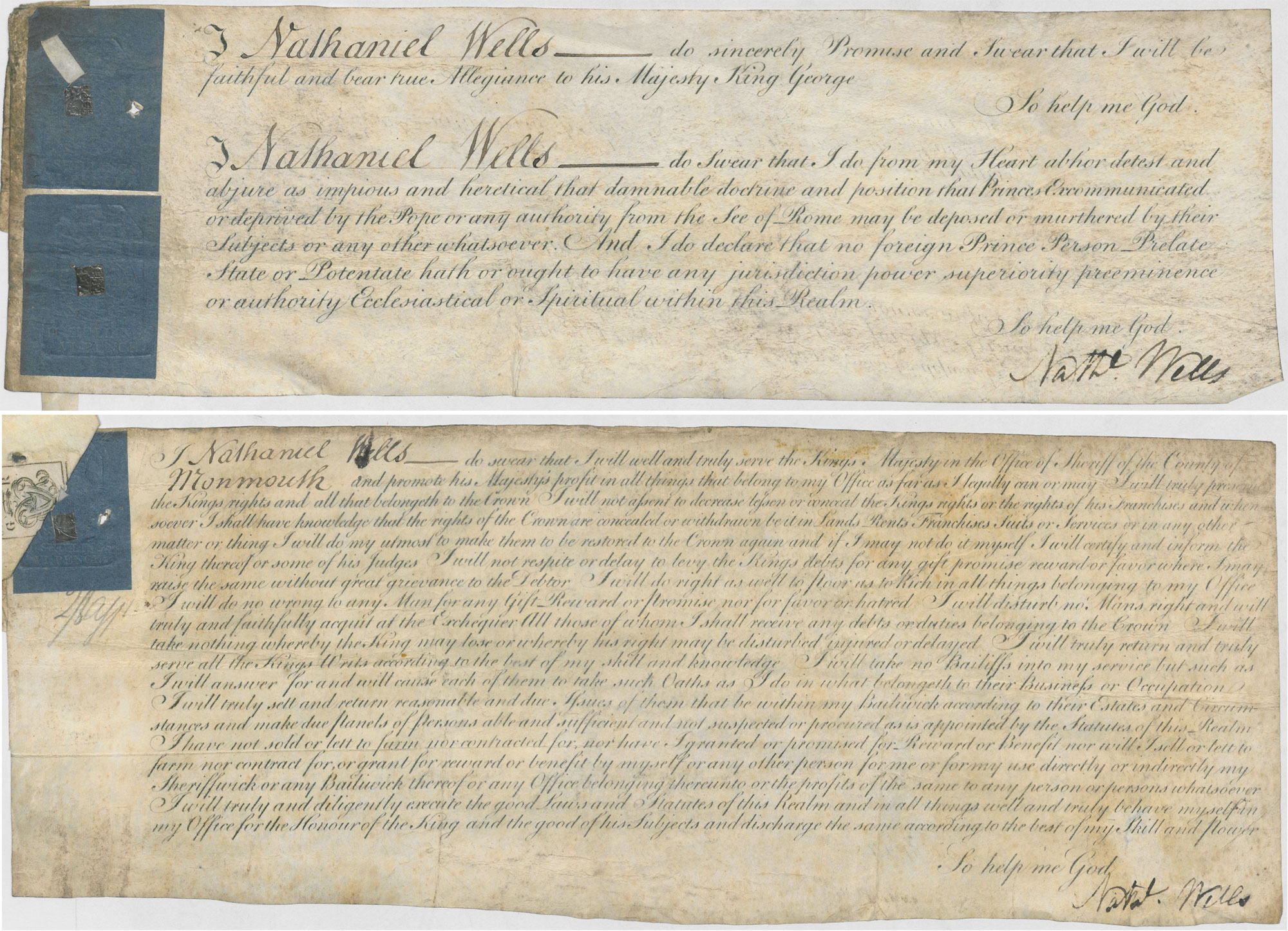

Nathaniel immediately took to a new life where he became very active in the local society and also became a church warden of St. Arvan’s Church. He was also a Justice of the Peace but most notably, Nathaniel became a Deputy Lieutenant of the County of Monmouthshire.

From 1818 through 1830, he served in an appointment as a High Sherriff of Monmouthshire, becoming the first person of African ancestry to occupy such an office.

While in that role, in 1820, Nathaniel got commissioned as a lieutenant in the Chepstow Troop of the Gloucestershire Yeomanry Cavalry. His commissioning made him the second man of African ancestry to hold a commission in the armed forces of the Crown.

In 1833, slavery was abolished throughout the British Empire. This meant that slave owners needed to release all their slaves but this was a difficult decision for slave owners, including Nathaniel. Unable to heed to the new law, Nathaniel, along with many other plantation owners, illegally retained their slaves.

It had become obvious that the slave owners were unhappy about releasing “property” without suitable recompense and, hence, they lobbied the British Government for compensation.

Nick Draper of University College London’s Legacies of British slave-ownership project told the BBC: “Wells [Nathaniel] relied on his enslaved people for his fortune. But at the same time, you have to ask what else he could have done beyond simply selling out.

“On larger islands like Jamaica, freed slaves could survive as subsistence farmers, but on islands like St Kitts there simply weren’t the social or economic structures in place to allow them to survive independently, enslaved people were utterly tied to the plantations.

“Even slave-owners who were queasy about slavery were very reluctant to take steps they saw as disruptive of the settled order of a slave society. Instead, they depended on the British state to provide an overall solution – including compensation for the slave-owners, which Wells himself also received.”

In 1837, parliament relented and paid slave owners to release their slaves. Nathaniel, along with hundreds of other plantation owners, duly accepted the compensation and released their slaves.

In 1850, Nathaniel moved to Bath to attend to his failing health but two years after (May 13, 1852), he died. He was 72 and left behind a fortune of over $12.3 million in today’s terms.

His 22 children from two different marriages split his fortunes.