Although the English, later on, became notable African enslavers, the trade has its origins in the bosom of the Portuguese and Spanish.

The historical record holds that in 1502, Juan de Córdoba of Seville became the first merchant to send an African slave to the New World. Since it was only in its early stages, merchants were allowed by the Spanish authorities to sell only one to three enslaved Africans.

By 1504, a small group of Africans, likely slaves, who were captured from a Portuguese vessel, made their way to the court of King James IV of Scotland.

However, when the English joined the slave trade in 1562 – 60 years after the Spanish – they soon scaled the trade in humans with devastating consequences to the Africans.

In October of 1562, John Hawkins of Plymouth became the first English sailor known to have obtained African slaves – approximately 300 in Sierra Leone – for sale in the West Indies.

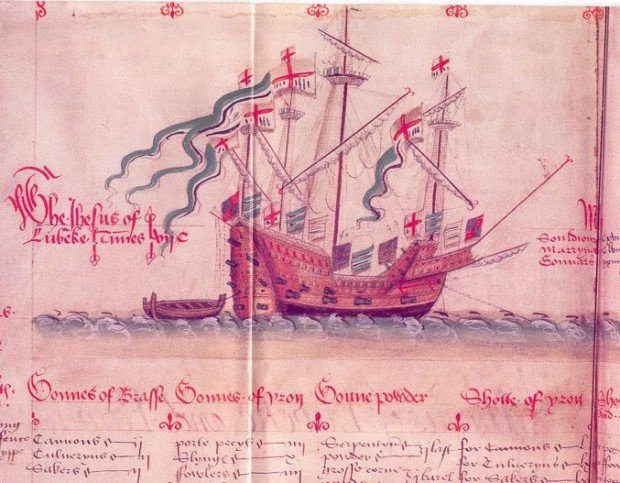

First slave ship Jesus

Hawkins traded the slaves illegally with Spanish colonies, but the trip was profitable and others followed. These contributed to increasing tensions between England and Spain.

John Hawkins’ father, William Hawkins, made the first English expeditions to West Africa in the 1530s, being an adventurous trader who set out to explore the Guinea coast in search of commercial materials such as dyewoods.

Hawkins, sailing to the Gulf of Guinea and venturing into Sierra Leone, captured 300-500 slaves, mostly by plundering Portuguese ships. He also used violence and subterfuge, promising Africans free land and riches in the new world.

He sold most of the slaves in what is now known as the Dominican Republic. He returned home with a profit and ships laden with ivory, hides, and sugar, beginning the slave trade for the English.

An account holds that Hawkins who claimed to be a devout Christian and missionary found the Sierra Leoneans harvesting their crops.

He then proceeded to tell the natives of a god named Jesus, afterwards asking which among them sought to have Jesus as their saviour. The hundreds who raised their hands were then led to the beach and his ship “Jesus of Lubeck,” also known as “The Good Ship Jesus.”

Urging the Africans to enter the ship for salvation, those who entered soon found they were barred from disembarking as the ship sailed and then got sold to Hawkins’ fellow slave merchants in the West Indies.

Jesus of Lubeck story

It is crucial to note that the 700-ton ship was purchased by King Henry VIII and 20 years later, it was Queen Elizabeth who lent the ship to Hawkins, effectively sanctioning the trade in humans and showing that English involvement in the slave trade was sanctioned at the highest level.

Curiously, Hawkins had a reputation for being a religious man who required his crew to “serve God daily” and to love one another. Services were even held on board twice a day despite the capture, detainment and sale of Africans against their will for profit’s sake.

Being cousins, Sir Francis Drake accompanied Hawkins on his 1562 voyage and others. Drake was claimed to be devoutly religious as well.

Is it any wonder then that persons claiming to be Christians see no problem inflating prices of items and goods to make illegal gains at their public sector departments or private companies as procurement officers?

Is it any wonder that politicians who profess their Christian faith lie even when they swear by the Bible in court to state the facts as they ought to yet commit perjury while others loot state funds funnelling it into offshore accounts?

Between 1562 and 1567, Hawkins and his cousin Francis Drake made three voyages to Guinea and Sierra Leone and enslaved between 1,200 and 1,400 Africans.

Mind you, these men, women and children would have contained some of the brightest, fittest and strongest the two states would have needed to develop and become mighty.

A loss, accounting for one of the steep costs African states have suffered, not to talk of the death of those who viciously fought back, those who got drowned while escaping and those simply beaten or clobbered to death.

With the slave trade proving more profitable than plantations, Hawkins’ slave-trading path involved sailing for the West African coast and, sometimes, with the help of other corrupted African natives, he kidnapped villagers. He would then cross the Atlantic and sell his cargo with others sold to the Spanish.

How Hawkins’ fate ended

Hawkins’ personal profit from selling slaves was so huge that Queen Elizabeth I granted him a special coat of arms. He was appointed as Treasurer for the Navy in 1577 and knighted in 1588 by the Lord High Admiral, Charles Howard, following the defeat of the Spanish Armada.

Hawkins’ slave business only concluded in 1567 not out of volition or repentance but because his fleet, which included a ship commanded by Francis Drake, took shelter from a hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico. The fight with the Spanish led to the loss of many of his men.

Hawkins escaped in one ship and Drake in another. He’d lost 325 men on that voyage, depleting logistics and his human resource although he recorded a financial profit.

In 1595, Hawkins accompanied his second cousin Sir Francis Drake on a treasure-hunting voyage to the West Indies. They twice attacked San Juan in Puerto Rico, but could not defeat its defences.

During the voyage, they both fell sick. Hawkins died on November 12, 1595, and was buried at sea off Puerto Rico. Drake succumbed to disease, most likely dysentery, on January 27, and was buried at sea somewhere off the coast of Portobelo in Panama. Hawkins was succeeded by his son Sir Richard Hawkins.

The End of the Slave Trade in England

Although England banned slavery in 1772, the trade in Africans continued after Hawkins, right into the 19th century across the colonies.

As with many things which cast aspersion on claims by enslaving states and people that they regret the slave trade, Hawkins has numerous public monuments in his name in Plymouth, including the Sir John Hawkins Square.

However, neither thousands of Africans killed and enslaved by Hawkins and Drake nor the millions who perished in the period that followed, have monuments erected in their memory, much more talk about reparation or financial support for African states affected by such vile acts.