Georgia county was one of the counties in the US that drove blacks away. Between the 1860s and the 1920s, it was almost the norm for white Americans to push out scores of black residents from their communities in what is otherwise termed as racial cleansing.

But a 1912 incident in Forsyth County, Ga., till date, is remembered as the largest case of black expulsion ever recorded.

In spite of the civil rights movement and the area’s proximity to Atlanta, the county remained virtually all-white into the 1990s after forcing out all 1,098 of its black residents – about 10 per cent of the population at the time.

Author and poet, Patrick Phillips, who grew up as a white boy in Forsyth, would later find in his research that the county had purged all its black residents to protect its white women after black men had allegedly raped and killed one woman.

His book, Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America, published in October 2016, recounts in detail the awful events of 1912 and their lasting impact on the county.

In the book, Phillips said he was in the second grade in 1977 when his family moved to Forsyth from Sandy Springs. They purchased a home in a white suburban setting in Forsyth, but Phillips soon realized that there were only a few blacks around.

“Why this white? Not one black person in the entire county? How could that be?,” Phillips was cited by an article in The New York Times.

He also observed that his classmates were comfortable with the N-word and there were occasional Ku Klux Klan rallies. So he sought to find out why.

“There was, in fact, a white woman who was murdered in 1912 and her name was Mae Crow,” Phillips said. “She was 18 years old and she was found under very mysterious circumstances beaten and bloody and unconscious in the woods.”

Even though there were no witnesses, the few young black men living in the area were accused of the crime. These young men were “outsiders,” teenagers taken in by their extended families and given a home in Forsyth County. Because they weren’t born there, they were automatically suspected of being behind the crime, The New York Times article said.

“A man named Rob Edwards was lynched almost immediately on the town square, and this turned out to be a lynching that most of the community participated in. Thousands of people showed up to watch the lynching and joined in and fired bullets into his corpse,” Phillips was quoted by History.

Two teenagers were arrested, including one who was forced to make a confession with a noose around his neck. The two, Ernest Knox and Oscar Daniel, were eventually tried and hung for murder.

Determined to avenge Mae Crow, Forsyth County’s whites subsequently turned their anger towards black people in the area. A white mob stormed the streets with dynamites, beating and burning down black homes.

Within a matter of weeks, Forsyth County was racially cleansed; every black person in the county had been driven out and the county enforced its borders as whites-only well into the 1980s.

According to Phillips, black families disbursed to different regions. While some were moving north in the Great Migration, others moved to the neighbouring county of Gainesville, Georgia county.

There have been claims that blacks were never driven out, rather, they left around that period because of the boll weevil and the Ku Klux Klan. But Phillips maintains that the white supremacist hate group and the insect mentioned were not around then, adding that it was the “government and law enforcement indifference that enabled ordinary white citizens to turn against their neighbours.”

“The Klan story was a way of deflecting guilt,” Phillips said.

It is significant to note that in 1910, Forsyth County had 1,098 black residents. By 1920, there were only 30 and this dropped to 17 by 1930, according to census data tracked by the National Historical Geographic Information System at the University of Minnesota and cited by AJC.

Many other communities in northern Georgia county attempted to expel their black residents in the early 20th century, but Forsyth would succeed, remaining nearly all-white throughout the rest of the century.

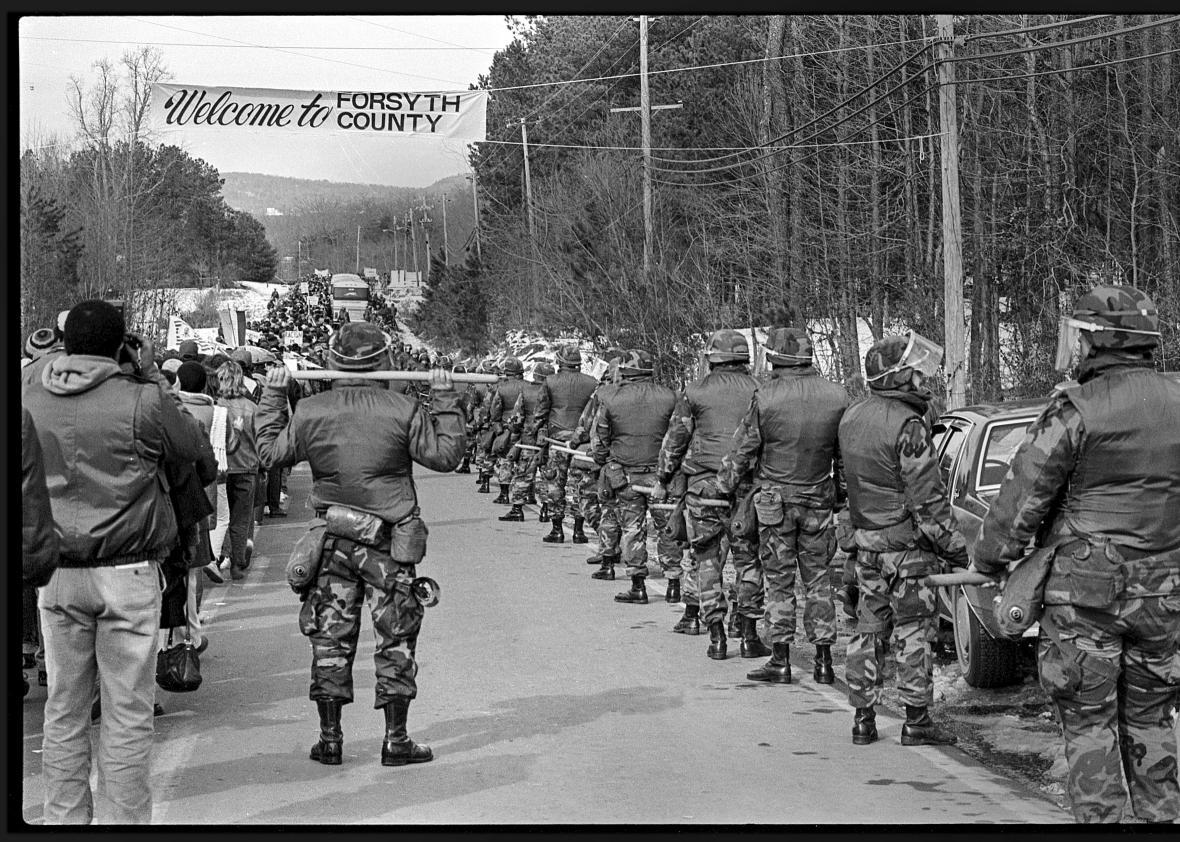

In 1987, some black American activists and their white allies who were fed up of the situation, held a civil rights march in Forsyth, declaring that the area was too white.

White residents responded by throwing rocks at the marchers, while Klansmen waved Confederate flags and kept shouting, “Keep Forsyth white.”

Oprah Winfrey also showed up with TV cameras in the wake of the rally.

Even with that, in 1990, only 14 black people lived in Forsyth. Phillips said that the march, however, kickstarted an inquiry into whether land that was illegally taken from black residents in 1912 could be turned over to those black residents’ descendants today. Since the land has been handed down or sold several times since then, the county did not redistribute any land, and may not do so in the future, according to an article on History.

What finally broke Forsyth County open “was the pressure of Atlanta’s sprawl and the onslaught of economic development,” said the New York Times article.

Today, Forsyth, a county that is one of metro Atlanta’s most affluent, is still heavily white and grapples with a racist image, observers say. 2015 census figures cited by AJC state that of the 212,000 people who live in Forsyth, 75 per cent of them are white. Blacks make up less than 4 per cent of the population, while Asians and Hispanics are the dominant minorities at 10.3 and 9.6 per cent respectively. Georgia county