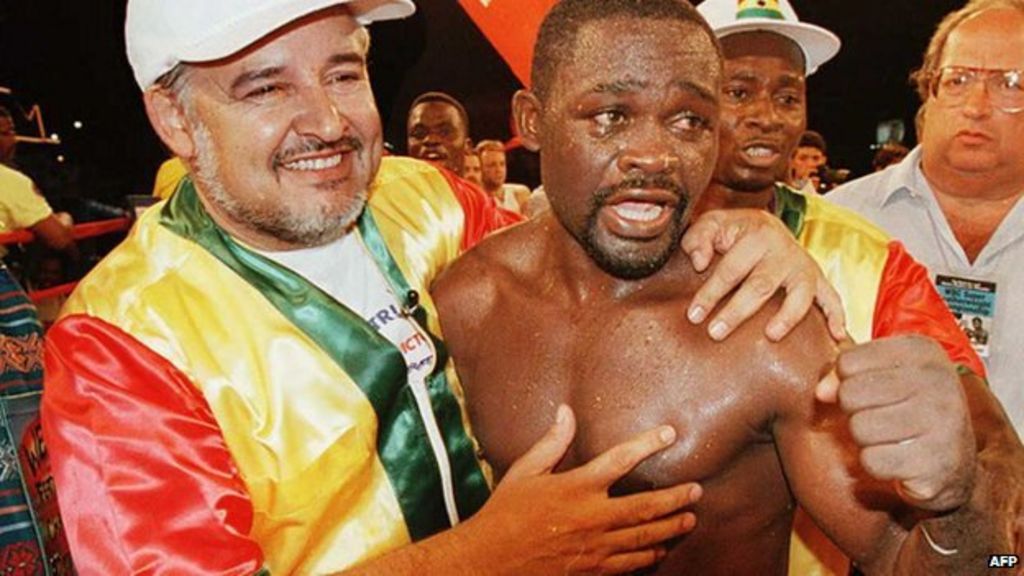

Azumah Nelson from Ghana, who, according to BoxNation and SkySports is the greatest African boxer of all time, once said that he always took his referee into the ring. This sentiment was formed a few years after an early career defeat when Nelson fell to a technical knockout (TKO) decision in Round 15 in 1982 at the Madison Square Garden.

Nelson did not think white judges and referees were fair to him. It was also not just about race; he was an underdog at that time and promoters do not like their nights messed up by some guy from obscurity.

Nelson felt that the only way he would be anointed the winner in the ring was if he knocked out his opponents. Judges may score unfairly and referees can make suspicious calls but Nelson’s hooks should not lie.

That is the meaning of taking his referee into the ring; taking things quite literally into his own fists. Nelson would go on to win 28 of his 47 fights via knockout.

This mentality and strategy served the man they call “The Professor” very well. And it was caused in him by the environment he knew while he grew up: Bukom.

It is impossible to speak of Ghanaian boxing without mentioning Bukom. But the bigger point here is being arguably Africa’s most successful international boxing country, Ghana is relevant to the sport, and that makes Bukom hugely significant in global terms.

D.K. Poison, Ike Quartey, Joshua Clottey, Joseph Agbeko and Richard Commey were/are all world champions at a point. And every single one of them was either raised or trained in Bukom.

But take a walk through Bukom, an inner-city community in Ghana’s capital Accra, and you may realise that the reality does not quite fit the reputation.

An area of just about two square miles, Bukom is overpopulated, impoverished and severely underserved. Sanitation is also a massive problem but in fairness, that’s Accra’s problem too.

So how does a community without the amenities, and frankly, no substantial evidence of promise, produce boxing’s best, year after year since the 1980s?

Survival. That is the answer.

Six years ago, Nelson himself told the BBC about Bukom: “When you are a child you need to find food for yourself, you need to struggle for yourself to get something to eat and get money. It makes you tough….Sometimes you just fight. Fighting is nothing, it’s not any big deal.”

Children, a good number of whom are born to poor and unemployed parents, learn that they have to become adults by their late teens. In Bukom, the developmental process comes in how many socioeconomic hurdles you have overcome before you reach about 18.

It is a poor community that shares many unifying principles yet, you stand alone if you are growing up in Bukom, Ghana. Although there is not a particular lack of schools, you do not expect education to be your way out.

Economic opportunities are virtually nonexistent for the few who avoided teenage childbearing and completed high school. Bukom is not very far from the Atlantic Ocean, thus, being a fisherman or a fish selling woman is always an option.

Or one can be a food vendor, selling less-than-nutritious meals in hygienically questionable conditions.

Interestingly, not very far from Bukom is Accra’s financial district that brings together multinational banks and powerbrokers. But this is not the chess or checkers for Bukom inhabitants; they are too poor to play.

Authorities have been well aware of Bukom’s plight for close to three decades. Accra’s mayors since the 1990s have spoken of plans to tap into the human resource of the people and better their lot.

This has not happened. Rather, it is common to see political party bigwigs show up for campaign rallies at the community centre known as Bukom Square to make newer batches of promises.

In such a place, people have nothing but their fighting spirit. And hands.

“It’s like a game”, said Agbeko, another former world boxing champion talking about the way his people fight in Bukom. But they would not just fight for fun or out of frustration.

Boxing provides a way to channel their energies into something that could take them out of the slum.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/63668350/commey_tr.0.jpg)

Boxing is the ticket out and when you do well, you can have a king’s welcome.

It is conventional to see Ghanaian winners of world titles parade their achievements on what are momentous occasions in Bukom. They went, they saw and conquered. The rest of the people have to know this.

From Nelson to current bright star Commey, everyone has gone through the streets of Bukom showing off their world titles won at megacentres in the US and elsewhere.

It is a source of inspiration for the young ones: Agbeko saw Ike Quartey fight; Clottey saw Nelson fight. An 8-year-old is now looking at Commey fight.

The belts are not the only inspiration. Boxing in ghana has done very well for these boxers who barely completed high school education and now, they can boast of wealth white-collar workers may not make in a 30-year career.

In recent times, a few of the boxers have given back by holding boxing clinics and opening gyms too. Some of them also sponsor the education ambitions of kids.

In 2016, the Ghanaian government opened a 4000-seater capacity boxing arena just outside Bukom. The facility, named after the community, is supposed to serve as a testament to what the people have given the country.

But only the most optimistic of people can believe this will help things in Bukom. The people cannot feed themselves and that is their bigger problem. Boxing seems like escapism.

And one wonders how many boxers a small community can produce. Bukom has already given the world more than its fair share even if there are still many up and coming world champion wannabes.

Agbeko put the situation better: “Any time you see a boxer from Ghana, you know they are very hungry… There is no room for failure. Either you win or you have nothing.”

These are people who are taking their referees into the ring. And they need to. Life is unfair.