Native American Heritage Month is a great time to highlight a relatively unknown part of one of the most special cities on the globe: the contribution of Native Americans to the musical universe of New Orleans.

Native Americans’ contribution to New Orleans’ music and culture is as deep and varied as were their relationships with New Orleans’ first Europeans, Africans, settlers and slaves.

The founder of New Orleans Jean Baptiste Bienvillle, along with his brother, observed some of the music and ceremonies of Native Americans in Louisiana. But one of the first European chroniclers was Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz. Du Pratz had a close relationship with Native Americans, especially the Chitimacha, during his 16-year stay in the territory. Du Pratz first described what he saw in his book History of Louisiana, published in 1758.

The first documented public event involving a musical procession in New Orleans was the “Marche du Calumet de Paix” (Peace Pipe March), which took place soon after Bienville founded the city in the spring of 1718. Although the calumet ceremony performed for Bienville was a new ceremonial form in the Lower Mississippi River Valley, “it was linked to tightly structured, ritualized protocols of interaction that stretched back for centuries, including the ‘playing of a flute-like instrument ‘which had in earlier periods ‘served an analogous role’ to the calumet throughout North America.” Du Pratz described the procession, how the Chitimacha danced in rhythm to a percussive instrument called a “chichicois,” a gourd with beans or pebbles placed inside of it to make sound.

The calumet ceremony was performed by the Chitimacha to greet Bienville and to signal a peace settlement. The procession was the culmination of a peace settlement between the French and the Chitimacha, who had fought a bloody seven-year war. The war had resulted in the mass enslavement and resettlement of the Chitimacha.

Another musical encounter in New Orleans was described by Father Pierre F. X. de Charlevoix in 1730. A delegation of Native Americans from Illinois Country traveled to New Orleans on a diplomatic mission. The Illinois and Kaskaskia tribes were known as the most “Christianized” tribes of the Illinois Country. They performed a Gregorian chant, with Ursuline nuns singing in Latin, and the Native Americans responding and singing each couplet in their own language. “This call-and-response between the Ursuline nuns and the Illinois in New Orleans also demonstrated how music could serve as a medium for interacting senses of spirituality.”

This diplomatic mission came a year after a land dispute between the French and Natchez had led slaves and Native Americans ( including the Choctaw, Yazoo, Tunica and other tribes up the Mississippi River Valley) to very nearly exterminate the French settlers. The Natchez Uprising had failed to completely rid the Mississippi Valley of the French, only because a Natchez princess foiled the coordinated attack.

Abundant Native American tribes occupied territory up and down the Mississippi River Valley area. They moved along the river and its tributaries, visiting kin, trading and interacting with other tribes.

As New Orleans grew, Native Americans camped and lived on the outskirts of the city in Bayou St. John and on Bayou Rd. Various tribes sold goods and earned wages as day laborers on the outskirts and inside the city. Indians interacted socially with slaves and early settlers, as well as participating in carnival celebrations.

Another musical spot on the outskirts of the city was Congo Square. On the one day of the week that the French law Code Noir mandated slaves be free from work, Congo Square became a place where slaves, Native Americans and free people congregated to socialize, dance, sell goods and play music. Code Noir allowed slaves to congregate and travel to public and private places on their day off. So, it increased the interactions between slaves and Native Americans.

Proximity to Native Americans bred intimacy. For example in 1808, before Louisiana was a state, Governor Claiborne wrote to James Madison that there were “several hundred persons held as slaves, who are descended from Indian families.” Just two years later the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled persons of color may be descended from Indians on both sides.” This ruling, for all practical purposes, made Native Americans black (free men/women of color).

Continued contact between African slaves and Native Americans had musical repercussions. Choctaws began to use “a unique wooden or vine strip” around drum heads to tighten them, a feature “similar to African drum traditions” and “potentially borrowed from drumming practices in Congo Square.”

Early French and Spanish settlers in Louisiana depended on Native American tribes for defense and survival. Native Americans and Free Men of Color made up a substantial part of the Louisiana fighting force in the War of 1812 and the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. The fighting force was so diverse that orders needed to be given in French, Spanish, and Choctaw. After the War of 1812, the Choctaw borrowed from the construction of “the European snare drum, stretching a taut cord across the bottom of their cedar bucket drums to give them the ‘snap’ of European drums.”

New Orleans was known to the Choctaw as Balbancha, “a place where people speak strange languages.” The language multiverse of New Orleans included the Native American languages (Choctaw, Natchez, Chitimacha, Houma, Tunica, Bayogoula, to name just a few), French and Spanish. The arrival of slaves to Louisiana added many African languages to the mix. Two other languages were also forming in early New Orleans: Louisiana Creole (a mix of French, Spanish, and various African and Native American languages) and Mobilian Jargon, a trade language developed between Europeans, Africans and Indians. This mix made Louisiana “the most compact multi-lingual part of the U.S.” New Orleans became a “language contact area.”

New Orleans became a world famous “ musical contact area” as well.

Different languages, like the music that became jazz, were the fusion of cultures that made and continue to make New Orleans something unique. Only New Orleans had the type of freedoms and interactions between African, Native American and European cultures to create this mélange.

Because of the strategic placement of the city, (at the end of the Mississippi Valley and on the Gulf of Mexico), many Indian tribes had been congregating in what became New Orleans long before Bienville established a European settlement in 1718. After the settlement, European and African music was added to the mix and influenced the Native American music in New Orleans. Music from the Caribbean and Latin America would also become part of the mélange that would eventually lead to jazz.

After the Indian Relocation Act of 1830, Mardi Gras Indians started to appear in New Orleans’ annual Carnival celebration as a show of solidarity with Native Americans. The Relocation Act forced the Five Civilized Tribes to lands west of the Mississippi. At the same time in the city of New Orleans people of color were banned from congregating and wearing masks in public in the lead-up to the Civil War.

Today’s Mardi Gras Indians symbolize the fusion and celebration of African and Native American cultures. Because of Louisiana’s unique society, African and Native American cultures and spirituality were not suppressed; instead, they flourished like no other place in the U.S. While slavery of Native Americans is rarely discussed in US history, the French allowed and sometimes encouraged Native Americans from different tribes to take captive during tribal wars or disputes. These captives were often sold into slavery. During French rule of Louisiana, slaves and Native Americans fought vigorously to rid Louisiana of slavery. The Natchez Uprising is just one of the many uprisings of slaves and Native tribes during French rule that serve as a symbol of native and black solidarity. The Spanish outlawed the slavery of Native Americans in Louisiana in 1763. By contrast, the American colonies did not outlaw Native American slavery until 1776.

Despite Anglo resistance and interference in the lives of Native Americans and other people of color, families that had Native American connections continued to influence the musical universe of New Orleans. Unknown to many, musicians with Native American ancestry participated in the development of jazz.

For example, my relative, bassist Alcide Pavageau, had a forty-year musical relationship with clarinetist George Lewis and his band. Lewis’ grandmother “was Choctaw, and during the early part of his musical career, Lewis maintained close ties to the Mandeville area on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, near Choctaw communities that still existed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.” Another example is “Tunica-Biloxi Harry Broussard, who toured the nation playing jazz saxophone, [often recalled] breaking into a Tunica song in the midst of a performance and how much the audience liked it.”

Native American Heritage Month is a great time to acknowledge the cooperation and the contribution Native Americans made with the black community of Louisiana. Highlighting their musical contribution to the musical universe of New Orleans helps to round out a story of cooperation, clashes and coexistence between Europeans, Africans and Native Americans and uncovers an unknown part of the musical history of one of the most special cities on the globe.

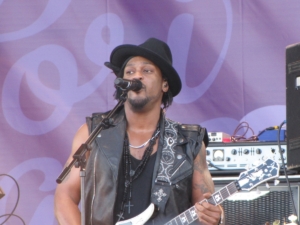

New Orleans’ world-famous Mardi Gras parade and celebration features the musical and dance procession of the Mardi Gras Indians. But the Mardi Gras Indians represent more than three centuries of the contributions Native Americans made to the culture and the music of this special city.

This article borrows heavily from Singing, Shaking, and Parading at the Birth of New Orleans

by Shane Lief.

All quotes come from this source found in THE JAZZ ARCHIVIST Volume XXVIII, 2015