The Malawian minister is today seen as a martyr of his country’s nationalism. In fact, every January 15, Malawians celebrate John Chilembwe Day to remember his uprising that is viewed as the beginning of the Malawi independence struggle.

John Chilembwe’s rebellion against British colonial rule did not receive wide local support as expected largely due to the extent of violence and bloodshed that shocked many at the time.

Despite being an independent-minded person, sources say Chilembwe was eager to learn from whites and to believe the best of them.

He would later gain a global perspective on the challenges of people of African descent, and this would influence the uprising in his home country that would cause havoc, including the beheading of a British plantation owner in front of his family.

Chilembwe was born in Nyasaland (today’s Malawi) around 1871 to a Yao father and a Mang’anja slave. The Yao (originally from Mozambique) were middlemen between the enslaving Arab traders and the Mang’anja slaves (the local tribal ethnicity).

Chilembwe grew up to witness the period in 1891 when the British colonized Nyasaland and took over from where the Arab traders began. The British authorities introduced newly-organised governance and missions through which they established a system of indigenous control, BlackPast said.

In 1892, Chilembwe met the Baptist missionary, Joseph Booth, who is described as “an eccentric, apocalyptic British fundamentalist missionary in Baptist persuasion” by historian Robert Rotberg.

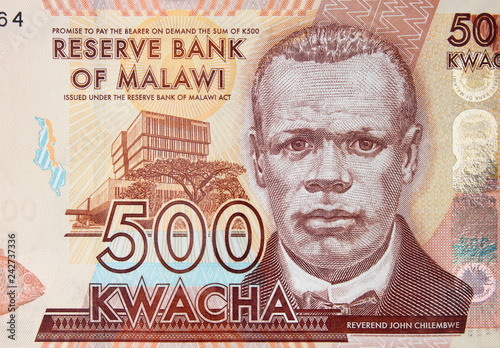

John Chilembwe on Malawi 500 kwacha (2014) banknote. Pic credit: Fotolia

Booth had then established the Zembesi Industrial Mission as an alternative to the already established Scottish Presbyterian missions that exploited the local people.

Chilembwe first applied to be Booth’s cook, but the two soon became close friends and allies. Booth educated his new friend on his egalitarian principles and baptized him on July 17, 1893.

Three years later, Booth had to travel to the United States to raise funds for his Mission. Chilembwe left with him, but the two would later go their separate ways on friendly terms upon their arrival.

Chilembwe subsequently attended Virginia Theological Seminary and College at Lynchburg, Virginia in 1898 and 1899, and would be exposed to the ideals of African-American preachers and radicals such as the Zulu missionary John L. Dube from South Africa and Lewis Garnett Jordan of the Negro National Baptist Convention.

Soon, he realized the need to confront racism, oppression and injustice and these would influence his thoughts when he returned to Nyasaland in 1900, having been ordained a Baptist minister in 1899.

Upon his arrival in his home country, the Malawian reverend, with support from the American National Baptist Convention, founded the Providence Industrial Mission, and by 1912, he had established several independent African schools and built a brick church – which was quite expensive in those days. He also developed plantations of coffee, cotton, and tea.

Getting closer to several leaders of independent African churches (AICs), including the Seventh Day Baptist and Church of Christ, Chilembwe hoped for a united African Christian front with his own mission at the centre, writes Ken Chitwood.

He also longed for a system of justice and equality, especially after having witnessed the cruelty of white colonial leaders, particularly on white estates that had Africans as tenants and wage earners.

One of these white plantation owners was Alexander Livingstone Bruce, who would openly condemn Chilembwe and AICs, describing them as “centres for agitation.”

The Malawian reverend soon began criticizing the British colonial racist society, but a series of events that followed would spur him to organise the brutal uprising.

To begin with, when Mozambique was hit by famine, refugees were mistreated; white settlers started to seize lands from locals, while the British also imposed a tax on African huts, forcing locals to move to urban areas to find jobs.

To make matters worse, the Malawian reverend ended up in debt, coupled with a struggle with asthma and the death of his daughter. Already frustrated over these events, the British conscripted natives to fight Germany in East Africa at the outbreak of World War I. This angered Chilembwe, forcing him to write a letter to authorities in protest.

“We understand that we have been invited to shed our innocent blood in this world’s war….[But] will there be any good prospects for the natives after…the war? We are imposed upon more than any other nationality under the sun…” excerpts of the letter said.

When the Malawian reverend did not receive a reply to this letter, he invoked the name of the American abolitionist, John Brown (who organized the attack on Harper’s Ferry in 1859) and organized an armed rebellion against the British.

Together with about 200 followers, the uprising began on January 23, 1915, with the aim to kill all white, male Europeans. The revolutionaries killed three British subjects, including Chilembwe’s adversary, Livingstone. Sources say he was beheaded in front of his wife and daughter.

The rebellion, however, failed to receive backing from locals, forcing Chilembwe and the revolutionaries to flee to Mozambique, where he was killed by African soldiers on February 3, 1915.

His uprising may not have been successful, nevertheless, the Baptist minister is today remembered as one of the forerunners of nationalism in Africa. His actions are also seen as a testament to the evangelical voices who are speaking against racism, injustice, and oppression across the world.