Postmaster Frazier B. Baker was murdered simply for doing his job. He was the first African-American appointed to serve as postmaster at the Lake City Post Office in 1897 and for this he was lynched for refusing to give up his post.

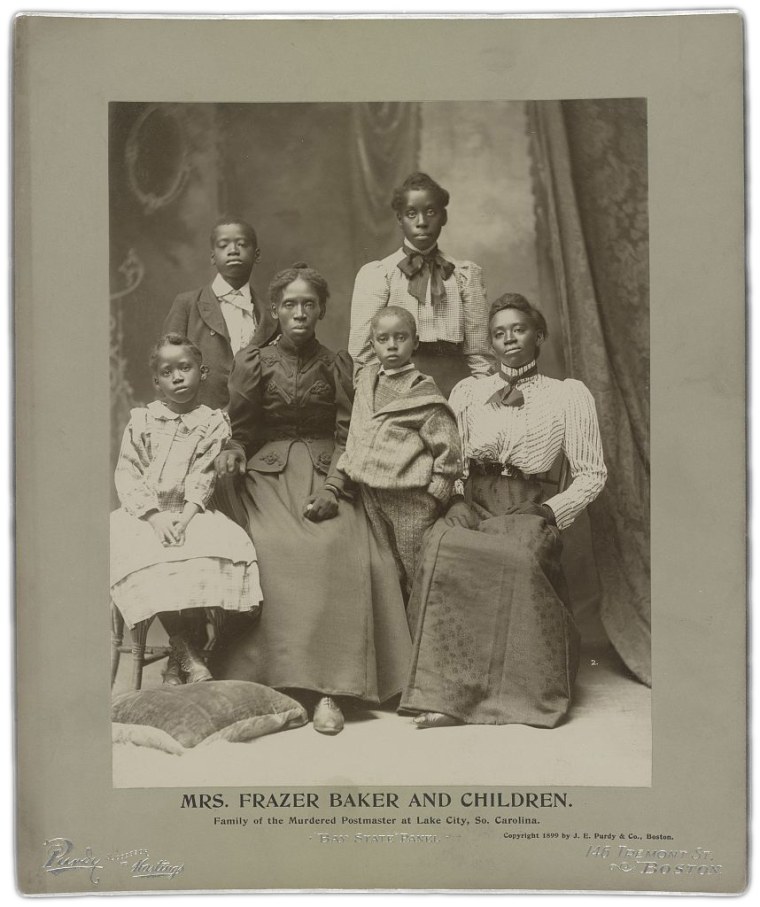

Baker and his infant daughter, Julia Baker, died at the family’s home on Feb. 22, 1898, after being shot during an attack by a white mob.

Baker was appointed as postmaster of Lake City, South Carolina in 1897 under the William McKinley administration. After the 1896 Presidential election, the Republican administration appointed hundreds of blacks to postmasterships across the Southern United States.

The local whites resented any black Republican officeholders, especially appointments made by an outgoing administration, fearing the blacks will be emboldened to retaliate past lynchings.

The local whites, however, objected to Baker’s appointment and undertook a campaign to force his removal. When these efforts failed to dislodge Baker, a mob attacked him and his family at night at their house, which also served as the post office.

The mob set the house on fire to force the family out. His wife and two of his other five children were wounded, but they escaped. Baker, a married 40-year-old schoolteacher and father of six children reported threats to his superiors in Washington yet little action was taken.

When the mob set fire to his home they were firing shots too. When a bullet struck and killed his two-year-old daughter, Julia, Baker informed his wife with the heat intensifying that they had to attempt running, but as he opened the door; he was cut down in a hail of gunfire.

“His wife Lavinia, wounded by the same bullet that had killed her daughter, rallied her family to escape the burning house, and they ran across the road to hide under shrubbery in an adjacent field. After waiting for the flames and gunfire to subside, Lavinia made her way to a neighbor’s home, where she found one daughter waiting. They were later joined by the oldest, Rosa. Rosa had been shot through the right arm and fled the house as an unidentified armed white male pursued her. Only Sarah (age 7) and Millie (age 5) escaped unscathed. The survivors remained in Lake City for three days, but received no medical treatment.

“The lynching was met with widespread condemnation, including across the South. The lynching was defended by those who agreed with South Carolina Senator Benjamin Tillman, who said the “proud people” of Lake City refused to receive “their mail from a nigger.””

Ultimately, 13 men were indicted in U.S. Circuit Court on charges of murder, conspiracy to commit murder, assault, and destruction of mail on 7 April 1899, after two men, Joseph P. Newham and Early P. Lee, turned state’s evidence in exchange for their charges being dropped.

The trial was held in federal court from 10–22 April 1899. The defendants were Alonza Rogers, Charles D. Joyner, Edwin Rogers, Ezra McKnight, Henry Goodwin, Henry Stokes, Marion Clark, Martin Ward, Moultrie Epps, Oscar Kelly and W. A. Webster.

The all-white jury was composed of businessmen from across the state. Newham, the prosecution’s star witness, admitted to starting the fire and identified eight of the defendants as having participated in the murders.

The jury deliberated for around 24 hours before declaring a mistrial; the jury was deadlocked in reaching a verdict, five to five. The case was never retried.

Lavinia Baker and her five surviving children remained in Charleston for several months after the verdict before settling near Boston.

The Bakers remained in Boston but out of public life. The surviving Baker children fell victim to a tuberculosis epidemic, with four children {William; Sarah; Lincoln, Cora} dying from the disease 1908-1920. Lavinia’s last surviving child, Rosa Baker died in 1942. Having lost all her children, Lavinia Baker returned to Florence County, where she lived until her death in Cartersville, South Carolina in 1947.

In 2019, the Lake City Post Office was renamed in honor of Baker and the sacrifice he made 122 years ago.