When a colleague refused to show her how to operate a computer, Raye Montague taught herself.

When she was asked to work night shifts before getting a promotion, she bought a car and learned to drive. When she was told that she couldn’t work nights alone, she brought her mother and son to work with her.

Those were the challenges Montague had to endure in her 33-year career at the U.S. Navy. In the face of explicit racism and segregation, this innovating woman would later make a major contribution to American military history in the 1970s – revolutionizing naval ship design.

The Little Rock “hidden figure” developed a computer programme that created rough drafts of ship specification. This allowed the Navy to cut the time it took to build a ship’s draft design from two years to 18 hours and 26 minutes, the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reported in 2012.

Becoming the first female Program Manager of Ships in the United States Navy and producing the first computer-made Navy warship design within a racial climate meant that Montague had to endure the above prejudices, and she did that “with a smile.”

“I had to run circles around people, but when they found out I really knew what I was talking about they came to respect me.”

“I worked long hours and

Born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1935, Montague grew up in a deeply segregated South. After completing high school in 1956, her mother told her of the challenges ahead for her.

“You’re female, you’re black and you’re going to have a segregated school education—so you’re going to have three strikes against you.”

“But you can do anything you want to do and be anything you want to be,” Montague recalled her mother saying.

Montague wanted to be an engineer. At age seven, her grandfather had taken her to see a German submarine that had been captured off the coast of South Carolina during World War II.

She became fascinated with the vessel and asked a worker at the site what she would have to do to work on such a ship.

“You’d have to be an engineer, but you don’t have to worry about that,” Montague recalled the worker saying without realizing then that she had been insulted.

Her hopes of studying engineering at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville got dashed because the school would not accept black students at the time. Thus, Montague obtained a business degree from the Arkansas Agricultural, Mechanical & Normal College, and then moved to Washington, D.C. to work as a typist for the Navy

Determined to work her way up, she studied computer programming at night and was eventually promoted to a digital computer systems operator and a computer systems analyst.

After one year, she secured another promotion despite the strict requirements of having to work nights. In her new role as the first female program manager of ships, the racism and sexism struggles did not cease but she was not deterred.

It was during this period – the height of the Vietnam War in the 1970s – when she was given the challenge that would change her life. Her supervisor gave her six months to create the first successful computer program for ship design, without informing her that the department had pursued that project for years without success.

Montague would later realise that her “racist” supervisor only wanted to get rid of her by giving her such an ominous task within limited time.

This required working day and night, yet, her supervisor was unwilling to pay any of the staff to work overtime with her, and also said that she could only work at night if she had someone with her. That compelled Montague to bring along her three-year-old son and mother to the office.

Taking note of her full commitment, the supervisor finally allowed a full night staff to help her create the programme. The then-president, Richard Nixon, immediately demanded to see plans for a computer-designed warship. Fired up, Montague called in her staff on a Saturday morning and started up a computer program that she had created. Under 19 hours, the first computer-generated rough draft of a U.S. naval ship had been created, a process that had, up to that point, taken two years.

Her draft evolved into the Oliver Hazard Perry-class frigate, one of the Navy’s longest-serving (and hardest-to-sink) platforms: 71 hulls were built in the U.S. and abroad, and about two dozen remains active in partner nations’ navies today, said The Maritime Executive.

Her programme became very significant to the design of warships and submarines. In 1972, she was granted the Navy’s Meritorious Civilian Service Award in honour of her work.

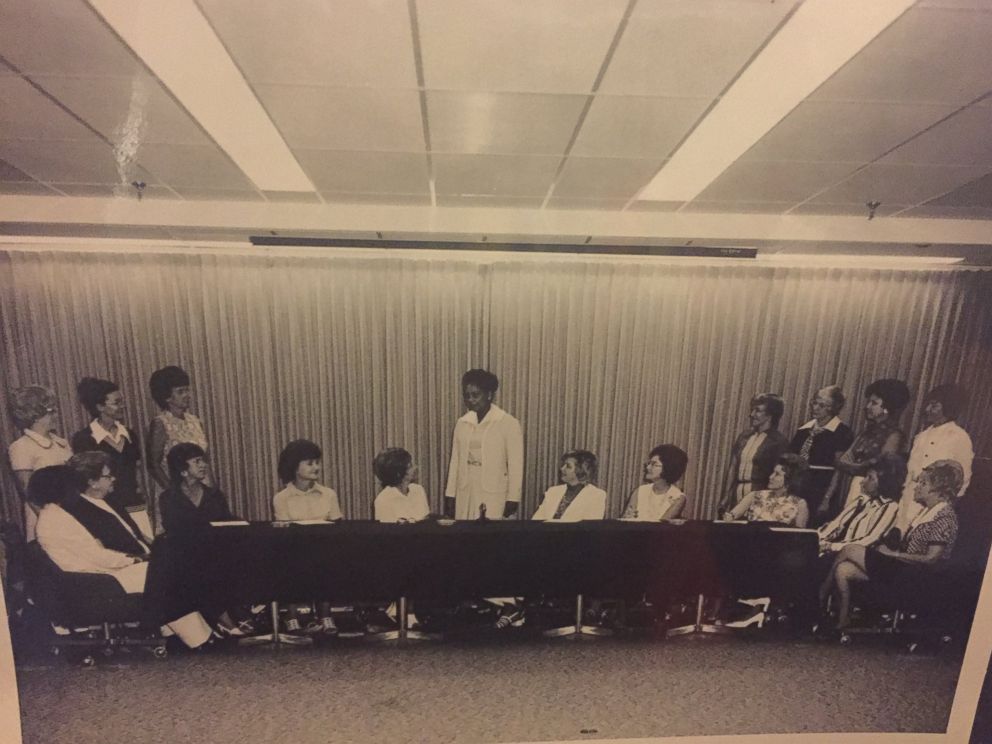

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-mco.s3.amazonaws.com/public/P47OKNTYCNCLTIDUGXLL4HTQCE.jpg)

Montague was also the first female professional engineer to receive the Society of Manufacturing Engineers Achievement Award (1978) and the National Computer Graphics Association Award for the Advancement of Computer Graphics (1988). She has also received other honours from military branches, industry, and academia.

Before her death in October 2018, Montague’s work gained more recognition after the release of the movie Hidden Figures in 2016. The film touched on the work done by black female mathematicians during the early days of NASA.

It is significant to note that while Katherine Johnson, Mary Jackson, and Dorothy Vaughan were breaking barriers at NASA, another “hidden figure”, Montague, was making history at the U.S. Navy.

In 2018, the 83-year-old was inducted into the Arkansas Women’s Hall of Fame this year, after her incredible feats and having paved the way for many women of colour in the engineering field.