The talk of slave trade brings back memories of the horrifying experiences of enslaved Africans working on plantations in the Americas and other parts of the world.

For over 400 years, these Africans were captured and chained, forced onto ships and taken into new lands, with some even dying before reaching their destinations. For those who survived, it began several hours of work on plantations on empty stomachs and the constant reminder that they were now moveable assets.

Then came criticisms of the practice – largely from clergymen, French Enlightenment philosophers, English abolitionists among others – who thought that slave trade was a violation of the rights of the victims.

By the late 18th century, abolitionist movements had emerged in areas around North America, England and France. The slaves also rebelled on their own through revolts, escapes, suicide and sabotage.

While most of these Africans were enduring the pains of slavery during this period in America and elsewhere, happenings in France, particularly the Revolution, and slave insurgencies in Saint Domingue, would compel French colonial masters to put forth a decree abolishing slavery on this day in 1794.

The abolition of slavery throughout the French colonial empire made it the first empire in the Atlantic World to do so, years before America and Britain.

Though France had several colonies in the Caribbean, the most important was Saint Domingue (now Haiti) as it was then a sugar island, and the French largely depended on it for economic growth.

Around 1789, France had about 500,000 slaves in Saint Domingue who worked as sources of labour for cotton, sugar and coffee plantations. These black and mixed race slaves had their behaviours regulated through a slave code, otherwise known as Code Noir, that among others prohibited them from entering French colonial territory or intermarrying with whites.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, the free mulattos of Saint Domingue began discussing the civil and political rights of free blacks regardless of their wealth and education.

While free men of colour had become educated and some were wealthy property owners, colonial laws excluded them from voting and holding office, among others.

Headed by a free and wealthy man of colour, Vincent Ogé, they will present their concerns to the National Assembly of France. In March 1790, the National Assembly granted full civic rights to all persons over twenty-five years old, who had certain income qualifications.

The French assembly, however, left it to the colonial assembly to decide if the men of colour would be included. They were excluded, reports The Abolition Project. Oge, by October 1790, had returned to Saint-Domingue, and realizing that the French governor had refused to remove the restrictions, he started a revolt, but was unsuccessful.

He was easily defeated, tried and convicted of treason before being brutally executed in February 1791. Accounts state that the image of his tortured death angered many in France, and this influenced the National Assembly to extend civil rights to freeborn men of colour in the colony.

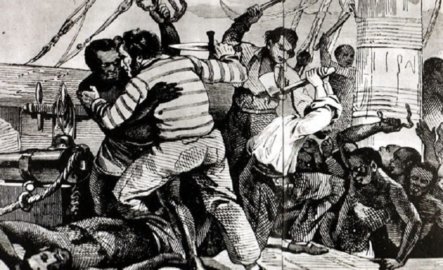

Yet, some plantation owners refused to abide by the new degree, and the enslaved, who were now more powerful than before following the frequent conflicts on the island, began a second revolt in August 1791. This eventually became the first successful slave revolt in history.

It all happened on the night of August 22 and 23, when enslaved people in Saint Domingue rose against their French enslavers and began the biggest and bloodiest slave revolt in history

Led by former slave Toussaint L’Ouverture, the slaves killed their slave masters, torched the sugar houses and fields and by 1792 they controlled a third of the island.

The National Assembly initially reacted by rescinding the rights of free blacks and mulattos on September 24, 1971, but this did not deter the slaves from their mission to obtain their freedom and eventual independence for the country now known as Haiti

While the fighting went on, the Legislative Assembly (which replaced the National Assembly in October 1791) met at the end of March 1792. The assembly voted to reinstate the political rights of free blacks and mulattos. They still did not make any decision about slavery and this fueled the ongoing rebellion.

France sent reinforcements but the area of the colony held by the rebels grew. At the end of the fight, thousands of blacks and the whites were killed.

Still, the blacks managed to turn away other French and British forces that arrived in 1793 to conquer them

Finally, realizing that the revolt was ruining activities in Saint Domingue, particularly the economy, the National Convention (which had also replaced the Legislative Assembly in France) voted to end slavery in all the French colonies on February 4, 1794.

White planters and mulattoes who owned slaves were angered by the decision and fled the island. But sources state that the decree did not totally solve the issue in the colonies as some landowners still enforced slavery in various forms and “victimized anyone who sought to stand for their rights”.

Napoleon Bonaparte, who was at the time the ruler of France, dispatched General Charles Leclerc, his brother-in-law, and over 40,000 French troops to capture L’Overture to enable him to restore both French rule and slavery.

L’Ouverture was taken to France where he died in prison in 1803. But Jean-Jacques Dessalines, one of L’Ouverture’s generals and also a former slave, led a series of revolutionaries at the Battle of Vertieres on November 18, 1803, where the French forces were defeated.

On January 1, 1804, Dessalines declared the country independent and renamed it Haiti.