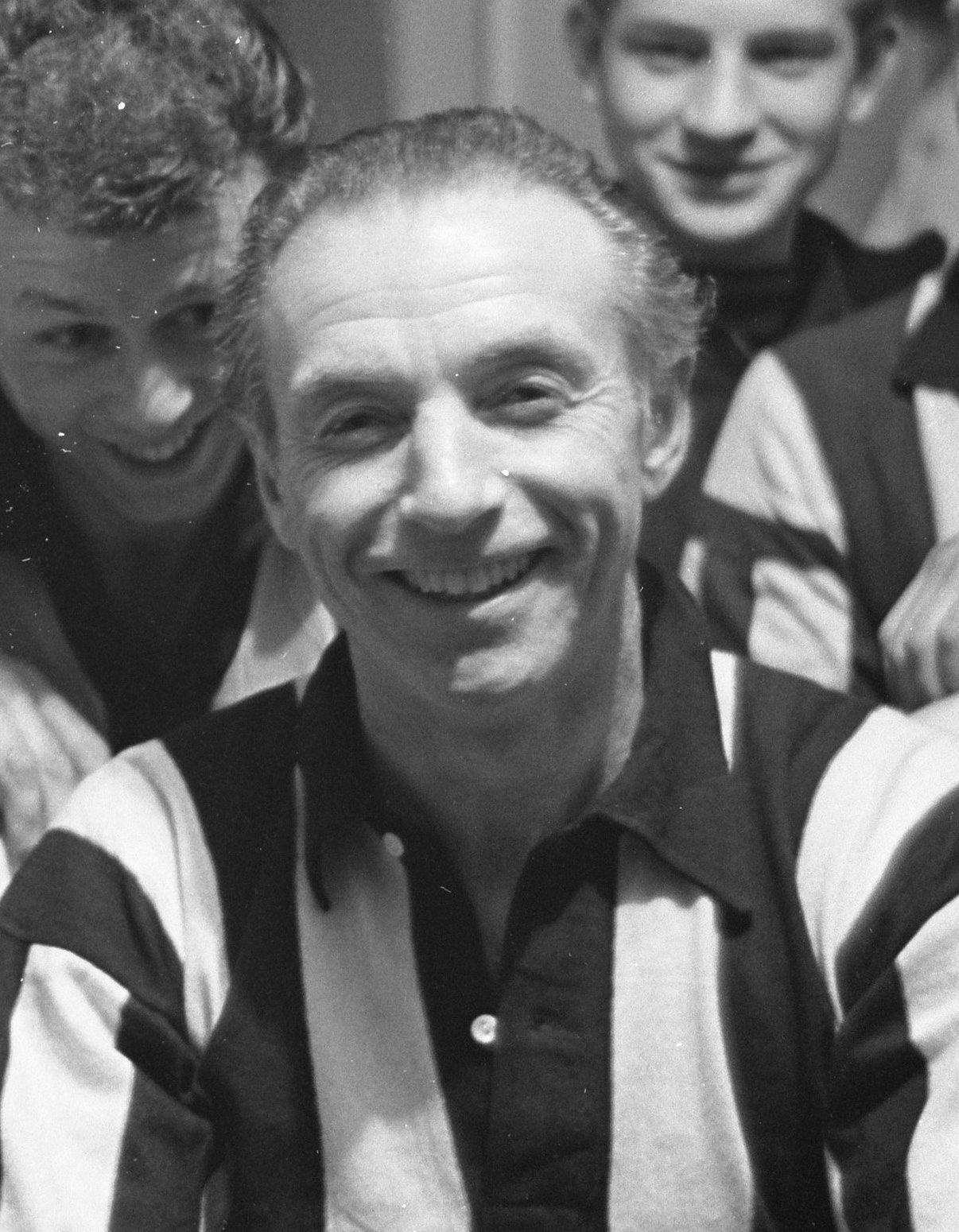

With the apartheid (1948 to early 1990s) leaders of South Africa being suspicious of foreign contact with their oppressed Black citizens, the feat by Sir Stanley Matthews in assembling an all-black soccer team which toured Brazil in 1975 is impressive.

Mathews had earned 54 caps for the English national team and had won the FA cup almost singlehandedly. He ventured into coaching after his stellar playing years and it was thanks to him a group of young men had a chance to meet Zico and to eventually play in Brazil.

The team now known as Stan’s Men under Hendrik Verwoerd, as other Black South Africans had been confined to homelands, required to carry a passbook to travel internally. They were thus surprised to see a white man in the stands watching their matches, and not only that, keen on having the best, form a team which could engage other teams outside South Africa.

In 1975, he took the boys from Soweto to Brazil, using his contacts to secure funding.

“At the airport I was riddled with nerves but tried to overcome them by busying myself shepherding my young charges and allaying their obvious fears. Large, forbidding men in light blue suits and dark glasses with inscrutable looks on their faces watched our every move but, uncomfortable as it was, they never approached us. At any given second I expected us to be rounded up, hustled into vans and taken away to one of South Africa’s infamous police stations but it never happened,” wrote Stanley in his autobiography.

“I couldn’t believe it and neither could Stan’s Men. We were on our way out of the country bound for Brazil, the first ever black football team to tour outside of South Africa,” he added.

They might have crossed over the border but the racist white government was not leaving things completely out of their hands as they planted a spy to follow the youngsters to Rio de Janeiro.

“On the Boeing 707, destined for Brazil, the lads were anxious and smart. They dressed neatly in tailored navy suits with a gold badge, with Stan’s Men printed on it, blue shirts, navy ties, with red and white dots, and shiny black shoes. Upon arrival in Brazil, they were treated like stars and journalists flocked around them. They felt like stars staying at the Hotel Regina, in Rio, on the famous Copacabana Beach. Most had never seen the sea.”

The team trained with Brazilian teams Flamengo, Fluminense, Vasco da Gama and Americana.

Matthews, the first European Footballer of the Year in 1956, saw his school boys from Soweto pummeled by Gama Filho University 8-0 in their first game which also starred 60-year-old Mathews, but the man who played top flight football until he was 50 called the ‘Wizard of the Dribble’ saw his boys get used to the ball and playing style of the Brazilians such that a 2-2 score line was recorded in the second game.

“That was embarrassing; their ball was different from ours. Our dribbling skills couldn’t get us anywhere. They man marked so tight that we couldn’t manage a single goal. Brazilians meant business; our goalkeeper left the field with swollen hands. He cried. If it was not for Sir Stan things could have been worse,” recalled Hamilton Majola, then aged 17.

“Sir Stan was a brave man, it was unlawful for white people to be in townships at that time but he was in Orlando every week to train us. He would come to our home to meet with our parents. Initially the parents thought we were crazy when we told them about going to Brazil but because Sir Stan was known to them they soon believed we were telling the truth,” Majola added.

“During those days, Orlando Stadium was our mecca of football. For the Brazil tour, it was not easy, we trained hard. There were hundreds of talented footballers from all over Soweto but only 15 could be selected. Dedication and discipline were key to Sir Stan,” stated Isaac Masigo, another youngster who boarded the plane for Brazil.

Mathews, a teetotaller and vegetarian, had instilled in the boys a need to do way with alcohol and not entertain women but at Copacabana Beach, that was a hard call.

“After the training, when Sir Stan was resting, we were free to go the clubs and beach. There was this Copacabana Beach, the best beach in the world. It was women galore, I sweated as if I was running under the sun,” stated Masigo, adding, “Sir Stan taught us life values; from the beginning he said we mustn’t go for girls because they would destroy our football future. He warned us against alcohol.”

Soon after Brazil, Matthews returned to England but he left a foundation in Soweto. The team continued playing friendly games, outside the country, in Swaziland and Botswana.

“I had seen and experienced what football could do for an individual and I wanted others to realize not only the possibilities that football can bring, but to get in touch with the possibilities that lay within themselves, irrespective of how hard and demeaning their lives were. If I could enjoy such benefit from football, I was determined to show others such benefits existed for them as well,” wrote Matthews.

Stans’ Men soon disbanded because of threats with the players plying their trade with other teams. Others left the country tired of the repression and keen on experiencing what the larger world had in store for them.

On Sir Stanley Matthews himself, he died on February 23, 2002, aged 85. On the trip which exposed them to the world, Stan’s Men rightly labelled it “a trip of a life time.”