In the last few weeks, there has been a fair amount of black history discussion, thanks in part to the movies "Lincoln" and "Django Unchained" the PBS documentary "The Abolitionist," and the inauguration of President Barack Obama to a second term. The rapturous nature of the entertainment industry’s interest in black history may give credence to those who argue that black history is now part of the mainstream and therefore Black History Month should be abolished.

Let’s be honest, we can’t concede the teaching of black history to movie producers and screenwriters. Fiction authors have the freedom to embellish or massage historical truths to fit their art or to entertain. It’s within an artist’s discretion to do so, and the onus to differentiate truth from fiction lies on their audience. Which is why black history needs to be incorporated in the school curriculum in a truthful, meaningful, and expansive way. Until then, Black History Month must serve as the means by which this is achieved.

Among Black History Month detractors are those who say it’s no longer relevant to the black experience, given that we now have a black man as president. Yes, it’s true that this is a stark indicator of socio-political progress, but a study of the context in which the president and his family have been received in certain factions of the society, as well the racial vitriol that has come to the fore, reveals that we’ve got a long way to go before we can claim victory.

The big leaps we’re making technologically and the rapid explosion of economies worldwide threaten to mute extensive discussions of history. Is it relevant for us to study history when the world we live in now is so much more advanced than that of our forefathers? Absolutely. Technology is evolving rapidly, but we’re not catching up as quickly in curbing prejudice. A quick survey of user comments in different news sites will confirm that smartphones and laptops and the Internet haven’t changed us, they’ve merely exposed us.

Economies are erupting worldwide, even as the gap between the rich and the poor expands. According to a New York Times report, if you walk the campuses of most top schools, you’ll discover that the vast majority are from upper income households. The decline of America’s meritocracy into a dynastic one doesn’t augur well for black people. Despite the rise of the African American middle-class, a 2011 study from Pew Research Center revealed that whites possess twenty times more wealth than African Americans. As Jean-Baptiste Karr famously wrote, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

The call for those of us who resist black history remembrance and seek only a national American identity is to embrace the fact that slavery, and all those who fought so valiantly for emancipation, is part of the nation’s collective self-identity. We can neither rewrite history nor escape the fact that we’re shaped by our social and cultural background. We should be challenged to self-reflect on this atrocious part of American history, and not universalize it by lumping it along with other nations’ prejudice crimes. We must understand our history in its specific context and dimension. This is the purpose for which Black History Month exists.

When I first moved to America, African American history was far from my mind. Like most Africans who migrated here freely, I came for the opportunities this country offers. I thought little of what it means to be African American. But as the years go by and I experience America more intimately in every sphere, I need for this discussion to continue—and if it must for only the twenty-eight days of February, so be it.

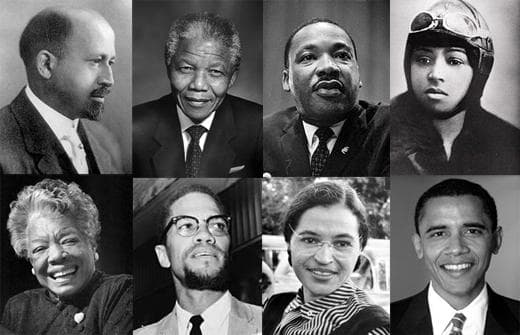

Recently, a friend’s four-year-old son stated that a fellow student had said that blue eyes see everything, brown and black ones don’t. Now, I’m not worried about my son’s friend because his parents are well equipped to nurture his self-esteem and identity. They’ve lived and thrived in this society. But what about the black child who is bombarded by these kinds of notions each day but has no cushion or mentors or guides? A public school where Black History Month is celebrated will expose this child to people just like him who’ve achieved great things.

Any children I have in this country will be African Americans. I would want them to understand their history, to celebrate our achievements, to give thanks for the sacrifices of those long gone, and to contemplate the complex nature of our present struggle. I would hope that this helps them grasp the pain of the past, and gives them the grace to wisely and bravely face the future.