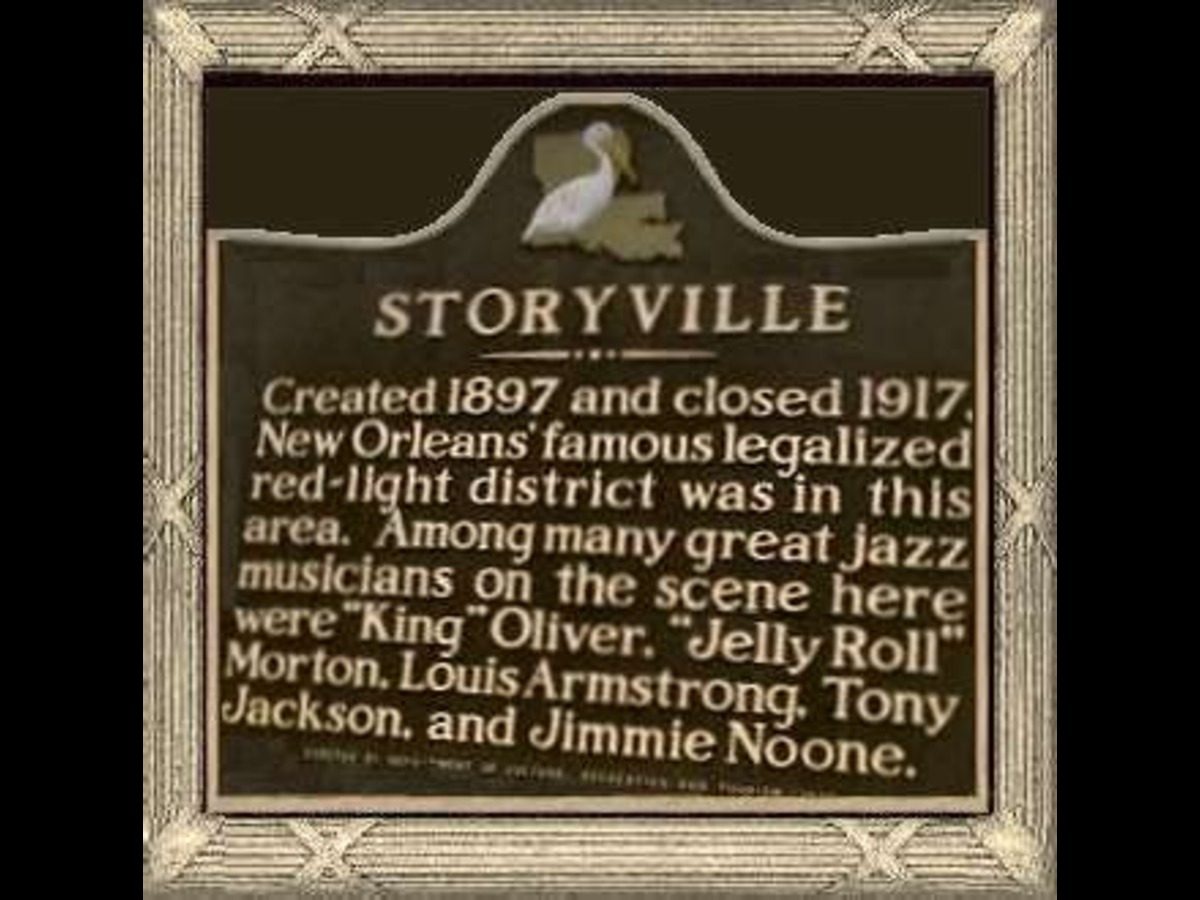

In 1897, Sidney Story, an alderman in New Orleans, put forth an ordinance confining vice to a 16-square-block area outside the French Quarter. The area was named Storyville after him, and has been commonly—but mistakenly—known as the birthplace of jazz.

While many black and Creole jazz musicians did perform in Storyville, people of color were not allowed to participate in its legendary excesses. Vice for people of color was confined to “black Storyville,” an area adjacent to Storyville, between Tulane and Poydras and Locust and South Basin streets.

Contrary to this myth, jazz music actually was being played by Creoles of color and black musicians decades before the creation of either Storyville or Black Storyville.

Eighty years before the establishment of Storyville, Congo Square, adjacent to the French Quarter, was designated by the mayor of New Orleans as an area where slaves could congregate on their day of rest. Here they were allowed to make music, socialize and mingle freely with each other and free people of color. Prior to the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, New Orleans had a full-blown opera scene. The Théâtre d’Orléans operated from 1819 to 1859, and the French Opera House, on Bourbon Street, operated from 1859 to 1919. Both venues permitted free people of color and slaves to attend.

Congo Square was at the heart of the Creole community. The Tios, Doublets, Picous, Pirons, St. Cyrs, Pavageaus, Hazeur and Baquet families all lived and thrived adjacent to Congo Square. These Creoles families were early innovators of jazz, long before Storyville was established.

Three years before Storyville, Sidney Story’s 1894 segregation ordinance made the French Quarter for “whites only.” It displaced these musical and other Creole families from a community they had lived in for decades and forced them “uptown,” the area where his vice district, Storyville, would soon be established.

The 1894 dislocation of well-to-do Creoles of color and black families from the French Quarter was happening against the backdrop of a resurgent wave of racism that was sweeping through the South. In 1896 the Supreme Court would decide the “separate but equal” Plessy v Ferguson case that would codify segregation and discrimination for the next 75 years in the U.S. In that same year, Louisiana created a “grandfather clause” for voting which said that those who had voted or had fathers and grandfathers who had voted before 1867 were exempt from literacy and poll taxes. Since no blacks had voted before 1867, they could not be exempted. By 1900, black voter registration had dropped from 45% to 4% in Louisiana.

A year before his vice ordinance was introduced and passed in 1897, Sidney Story and his friend, political boss and state legislator Tom Anderson, bought up all the available real estate in the area which then became Storyville. Storyville became known as a place where Anglo visitors could have encounters with women of color, and Story and Anderson, the new landowners, charged prostitutes double the usual rent for the “cribs” they used.

The biased myth of Storyville as a place that blacks and whites indulged and participated in every type of debauchery is untrue. In fact, Storyville was mainly a place where Anglos indulged their vices and people of color were allowed in as professional musicians and sex workers. Even vices were segregated.

Anderson became known as the “Mayor of Storyville.” He went into business with the notorious madam Josie Arlington, who ran a brothel on Customhouse Street. Anderson established the Fair Play Saloon, later to be known as the “Arlington Annex,” around the corner, at Basin and Customhouse Streets.

The law displacing Creoles from the French Quarter and the establishment of Storyville as a vice area accelerated the development and recognition of the music we call jazz. It forced Creoles of color—including many musicians who were classically trained and influenced by Congo Square and opera—to move from “downtown” to “uptown”—an area where black musical virtuosos were often self-taught and new to the city. These two dynamic groups created a musical fusion in Uptown New Orleans. The entertainment venues of the newly created vice district of Storyville and Black Storyville, and the resurgence of Congo Square as a place used by Creole of color musicians for brass bands, provided additional places for these musicians to perform and expand their genre.

The false narrative of jazz being born in Storyville needs to be debunked, as it makes the premier American musical genre seem forged out of brothels and speakeasies. Born many years earlier than Storyville, jazz was played in houses, at soirees, community events and fund-raisers by Creole musicians. It was forged instead from the musical stewardship, education, cooperation, intense imagination and innovation that was New Orleans’ Creole of color and black culture.

The history of New Orleans is about the interaction of different races and cultures that make it one of the most unique places in the world. With its African, Native American, Caribbean, Spanish, Mexican and European influences and musical heritage, New Orleans was the only place jazz could have been created. The fact that during segregation so many white musicians from New Orleans like Jimmy Durante, Papa Celestine, and Pete Fontaine had musical collaborations and friendships with musicians of color like Achille Baquet and Alphonse Picou shows the true character of New Orleans and the jazz genre itself. Like races and cultures musical rules that separate different musical genres needed to be crossed to create something new and unique.

It is more important now than ever that we challenge consumers of history with fact-based narratives. A new group of historians are pushing back on the biased history that has dominated the discussion up to present day. The soon to be released documentary The Reconnect: The Untold History of Jazz will explore this story in a way that has never been done before.