Exactly 185 years ago today in Britain, an act of Parliament came into force abolishing slavery in most British colonies, freeing more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa as well as a small number in Canada.

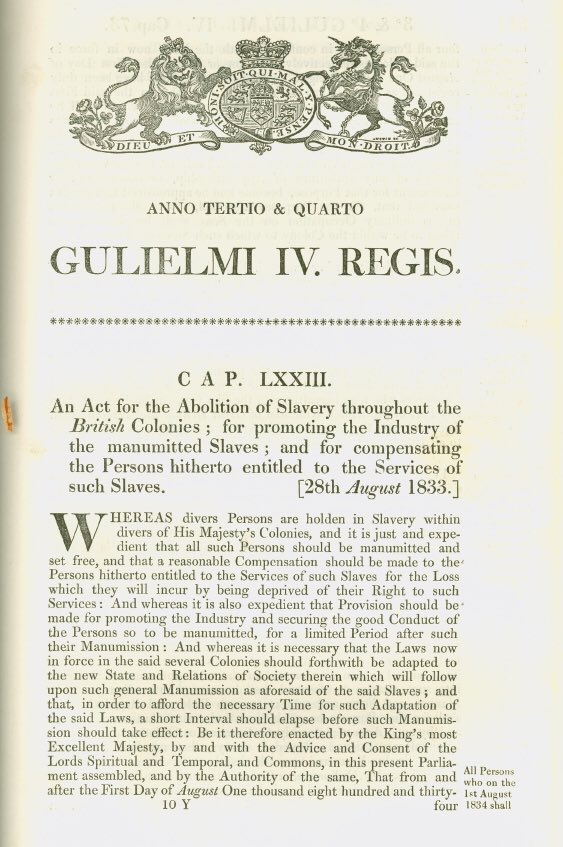

The act had received a Royal Assent on August 28, 1833, but only took effect on this day the following year (1834).

Before this decision, some British abolitionists had, since the 1770s, actively opposed the transatlantic slave trade of African people. Actually, several abolitionist petitions were organized in 1833 alone, which collectively garnered the support of 1.3 million signatories against the practice.

But other several factors culminated to this decision eventually. At the time, the economy of Britain was in flux as a new system of international commerce emerged. Britain’s slave-holding Caribbean colonies—which were largely focused on sugar production—could no longer compete with larger plantation economies such as those of Cuba and Brazil.

Merchants then began to demand an end to the monopolies on the British markets that were held by the Caribbean colonies and rather pushed for free trade. The persistent struggles of enslaved Africans and a growing fear of slave uprisings among plantation owners became another major factor.

The influence of the growing antislavery views from Britain begun to spread so much as to Upper Canada, influencing the passage of the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery there – the first such legislation in the British colonies.

In 1793, for instance, Pierre-Louis Panet, a popular political figure, introduced a bill to the National Assembly to abolish enslavement in Lower Canada, but the bill languished over several sessions and never came to a vote.

In February 1798 for instance, an enslaved woman named Charlotte was arrested in Montréal and was stopped from returning to her mistress. She was brought before James Monk, a justice of the King’s Bench with abolitionist sympathies, who released her on a technicality.

According to British law, enslaved persons could be detained only in houses of corrections, not common jails, and no houses of correction existed in Montréal. Charlotte and another enslaved woman named Judith were accordingly freed that winter. Monk stated in his ruling that he would apply this interpretation of the law to subsequent cases.

Rulings in such cases did not always favour emancipation. Only two years after the trials of Charlotte, an enslaved woman named Nancy petitioned for her freedom in the New Brunswick courts. Fourteen years earlier, Nancy had run away with her son and three others, but they were caught and returned to her owner, a farmer and Loyalist settler named Caleb Jones. The challenge filed by her attorneys was that slavery was a socially accepted custom but was not officially recognized in New Brunswick. The judges’ decision was split, and Nancy remained enslaved.

For most enslaved people in British North America, however, the Act resulted only in partial liberation, as it only emancipated children under the age of six, while others were to be retained by their former owners for four to six years as apprentices. The British government made available £20,000,000 to pay for damages suffered by owners of registered slaves, but none of the money was sent to slaveholders in British North America. Those who had been enslaved did not receive any compensation either.

The Act also made Canada a free territory for enslaved American blacks. Thousands of fugitive slaves and free blacks subsequently arrived on Canadian soil between 1834 and the early 1860s.