When it became clear that the directive for desegregated public schools that is allowing Black children to be educated in public schools along their white counterparts was still being resisted despite a Supreme Court’s, Charles Cobb proposed an alternative as did Algebra Project founder, Bob Moses.

“In late 1963, Charles Cobb, a Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activist, proposed the organization sponsor a network of Freedom Schools, inspired by examples of the concept used previously in other cities. In the summer of 1963, the county board of education in Prince Edward County, Virginia had closed the public schools rather than integrate them after having been sued in a case following Brown vs. Board of Education, and so Freedom Schools emerged in their stead,” stated NPR.

The Freedom Schools, alternative and free schools for African Americans mostly in the South were originally part of a nationwide effort during the Civil Rights Movement to organize African Americans to achieve social, political and economic equality in the United States. The most prominent example of Freedom Schools was in Mississippi during the summer of 1964.

In the mid-1960s Mississippi still maintained separate and unequal white and “colored” school systems. On average, the state spent $81.66 to educate a white student compared to only $21.77 for a black child. Even the curriculum was different for white and black in Mississippi.

“In September, 1963, about 3,000 students participated in a Stay Out for Freedom protest in Boston opting instead to attend community-organized Freedom Schools. On October 22, 1963, known as Freedom Day, more than 200,000 students boycotted the Chicago Public Schools to protest segregation and poor school conditions, with some attending Freedom Schools instead. Subsequently, on February 3, 1964 in a similar Freedom day protest, over 450,000 students participated in a boycott of the New York City public schools in what was the largest civil rights demonstration of the 1960s, and up to 100,000 students attended alternative Freedom Schools.”

The Mississippi Freedom Schools were also developed as part of the 1964 Freedom Summer civil rights project, a massive effort that focused on voter registration drives and educating Mississippi students for social change. The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) – an umbrella civil rights organization of activists and funds drawn from SNCC, CORE, NAACP, and SCLC – among other organizations, coordinated Freedom Summer.

The project was essentially a statewide voter registration campaign because the systematic exclusion of black voters resulted in all-white delegations to presidential primaries.

In March 1964, a curriculum planning conference in New York was organized under the sponsorship of the National Council of Churches. Spelman College history professor Staughton Lynd was appointed Director of the Freedom School program.

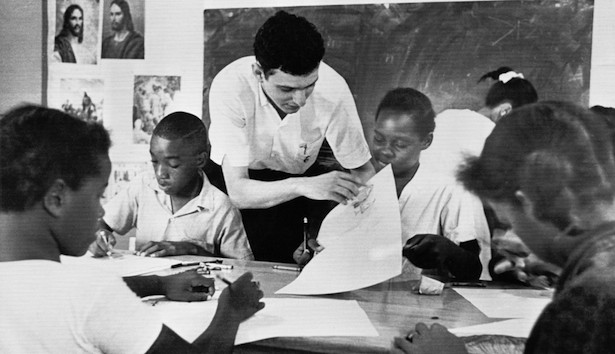

Over the course of Freedom Summer, more than 40 Freedom Schools were set up in black communities throughout Mississippi. Over 3,000 African American students attended these schools in the summer of 1964. Students ranged in age from small children to the very elderly with the average approximately 15 years old. Teachers were volunteers, most of whom were college students themselves.

“Through reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and civics, participants received a progressive curriculum during a six-week summer program that was designed to prepare disenfranchised African Americans to become active political actors on their own behalf (as voters, elected officials, organizers, etc.). Nearly 40 freedom schools were established serving close to 2,500 students, including parents and grandparents.”

“Freedom Schools were established with the help and commitment of local communities, who provided various buildings for schools and housing for the volunteer teachers. While some of the schools were held in parks, kitchens, residential homes, and under trees, most classes were held in churches or church basements. Attendance varied throughout the summer. Some schools experienced consistent attendance, but that was the exception. Because attendance was not compulsory, recruitment and maintaining attendance was perhaps the primary challenge the schools faced.”

Freedom Fighters also forced Southern states to admit a handful of black students to all-white schools. Mississippi reluctantly desegregated its schools in 1964, becoming the last state in the country to do so.

A small yet vocal number of African American students opted to boycott the public schools altogether. They questioned the logic of entering white classrooms that had reacted violently to desegregation orders. For students who boycotted their public schools, Freedom Schools served as a replacement for conventional classrooms.

Other Freedom School students remained in their segregated schools once the summer was over but demanded improvements. They insisted that white educators include African American history and literature in the curriculum. When Freedom School students were suspended for wearing “One Man, One Vote” buttons in the Delta, students walked out and shut down the school. The court case that followed was used as precedent in Tinker v. Des Moines (1969), which protected students’ right to free speech.

Part of the Freedom School legacy can be seen in the dozens of schools that hold the name today including the Freedom Schools in St. Louis, Missouri and Chicago, Illinois; Paulo Freire Freedom School in Tucson, Arizona; and Jane Addams School for Democracy, in St. Paul, Minnesota.

“A segment of the Freedom Riders, activists who painstakingly sat in at segregated bus terminals in 1961, organized the project. When they moved to Mississippi to register voters, young people called them “Freedom Fighters.”

Their presence inspired a level of terrorism that had not been seen in the South since Reconstruction. From June to August 1964 alone, police arrested more than 1,000 protesters and local segregationists murdered three freedom workers, assaulted over 80 activists, opened fire on demonstrators over 35 times, and set fire to 35 churches. Activists remained undeterred. During the course of the summer, they successfully pressured Congress to end a seven-week filibuster and pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.