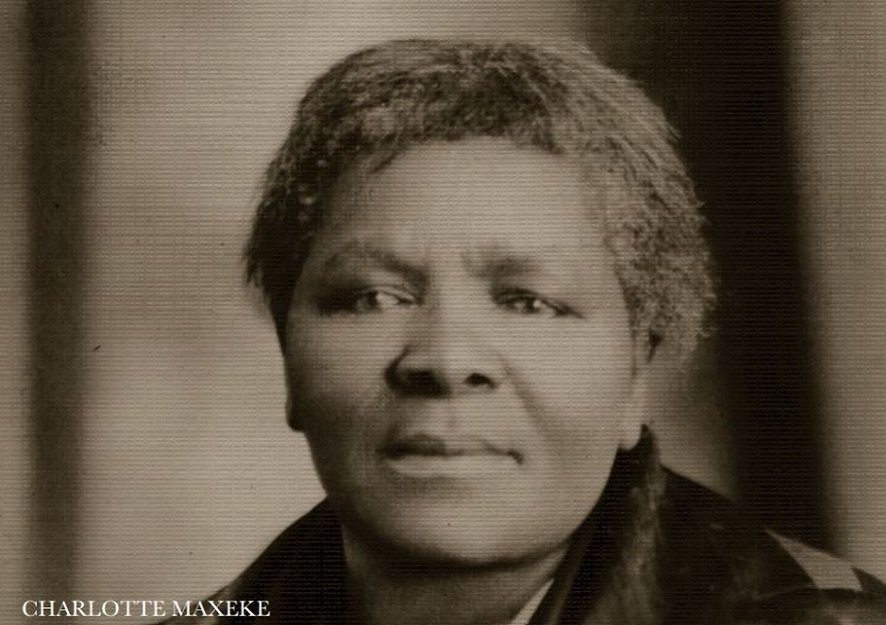

Often honoured as ‘Mother of Black Freedom in South Africa’, Charlotte Maxeke (maiden name Manye) lived at a time when repressive colonial laws meant that she could not acquire further education in her own country.

Braving the odds, Maxeke would travel the world as a choir singer at a time when women and people of colour were prohibited from doing so and would end up studying at Wilberforce University in Ohio, graduating with a BSc degree in 1901.

It was there that her political and social ideas took shape, and she would return to a segregated South Africa to teach while dedicating her life to the struggle for women’s rights and education for all.

Largely involved in one of the first influential women’s movements in her country, Maxeke believed that women and Black South Africans, in general, should be treated with respect. She probably never envisaged that a cruel system of apartheid will emerge in South Africa and wreak havoc for years.

Born in 1874 near Beaufort West, South Africa, not much is known about Maxeke’s early life, apart from the fact that she attended mission schools including Edwards Memorial School in the Eastern Cape in the early 1880s, where she learned Christian values that would influence her actions in later years.

Accounts state that after the discovery of diamonds, Maxeke moved to Kimberley with her family in 1885 where she worked as a teacher and became a dedicated churchgoer before joining the African Jubilee Choir with her sister in 1891.

Maxeke was soon invited to tour England as part of the choir and subsequently to Canada and the U.S., an unusual feat for many black women at the time. The group left Kimberley in early 1896 and sang to large excited audiences in all of the major cities of Europe, including royal performances where Maxeke once performed for Queen Victoria during the queen’s 1897 Jubilee at London’s Royal Albert Hall.

But the unfortunate soon happened when the trip ended after the choir organizer abandoned the group in the U.S. without money, passports, or any means to return home. Maxeke and most of the choir singers were left stranded on the streets of New York City.

The faculty and staff at Wilberforce University, an African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church-sponsored institution who heard about this development came to the aid of Maxeke and offered her a scholarship to attend the university. There, Maxeke was taught under the tutelage of Pan-Africanist scholar Dr W.E.B Du Bois and received an education that was centred on developing her as a future missionary in Africa.

By 1903, Maxeke had become the first black South African woman to earn a university degree and would later be married to fellow graduate and Xhosa born, Dr. Marshall Maxeke. She had then already joined the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church, founded in the U.S., which believes and preaches that Black people are no less human than white people.

With these background thoughts, Maxeke returned to South Africa in the 1900s and began teaching in Pietersburg while working on opening the first AME college in South Africa.

Together with her husband, Maxeke preached and taught the Gospel, as well as advanced the cause of education as the only route to a prosperous and fulfilled life for the Africans of South Africa, writes Daluxolo Moloantoa in The Heritage Portal. The couple also founded a primary and secondary school called “Wilberforce Institute” in Evaton, South Africa, named after their American alma mater.

In 1912, Maxeke and her husband were present at the launch of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the forerunner to the African National Congress (ANC), in Bloemfontein, where she addressed the social and political issues of women.

Five years later, in 1918, the activist and social worker founded the Bantu Women’s League (BWL), the women’s arm of the ANC, where she was involved in anti-pass campaigns in Orange Free State. The campaign was to protest non-white South African women being required to carry documentation of formal employment, a move that inhibited freedom of movement. Bantu Women’s League was basically formed to force the government to abandon the use of passes for women.

Maxeke was also involved in protests on the Witwatersrand about low wages and played key roles in the formation of the Industrial and Commercial Worker’s Union (ICU) in 1920. She continued to promote women’s rights serving as Women’s Missionary Society’s president in 1920.

After her husband’s death, Maxeke went ahead to fight for women’s rights. In 1928, she attended an AME Church conference in the U.S., and also addressed the All African Convention in Bloemfontein, where she played a huge role in the establishment of the National Council of African Women (NCAW).

The social worker eventually raised concerns about the struggles of black youth, and would later accept a position to be the first black woman to become a Probation Officer for juvenile delinquents in the juristically district of Johannesburg, according to The Heritage Portal.

Maxeke passed away in 1939 at age 61, and is currently remembered as one of the influential black people of the early 20th century, even though her name was largely written out of history books until today.

“Maxeke rolled up her sleeves and got to work. She made up her own mind about where to focus her energies. She chased her dreams and came into her own – defying the architects of both colonisation and apartheid. Hers was a triumphant spirit that powered on in spite of the multitude of odds staked against her. It is the courage and strength of the women of the time, Maxeke and many others, which is the focal point, as well as the history of resistance by black women,” writes Zubeida Jaffer in the book ‘Beauty of the Heart, The life and times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke.’

Today, a statue has been erected of Maxeke in Pretoria’s Garden of Remembrance while the hospital formerly known as Johannesburg General Hospital is now the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital.