Maude E. Callen’s contribution to safeguarding the health of African-Americans is profound. Having graduated from the Florida A & M University in 1922, as well as, completing her nursing course at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, she dedicated herself to her people.

Although Callen was born in Quincy, Florida, she moved to Pineville, South Carolina in 1923, where she practiced. Being an orphan from age six and raised by Dr. William J. Gunn, a physician who was also an uncle, Callen developed an interest in healthcare as well as resolute nature.

When she began operating from her home, she was one of nine nurse-midwives in the area. As an Episcopal missionary nurse, she operated a community clinic out of her home, miles from any hospital. She served people in an area of 400 square miles who either came to her or she went over traveling on muddy roads. She was the sole health-care provider, teacher and nutritionist in many instances.

While some contend she delivered between 600 and 800 babies in her years of practice, others put the figure at over 1000.

When the celebrated photojournalist, W. Eugene Smith, dedicated time to Callen, seeing first hand her impact on the people, it led to a December 1951, Life magazine publication.

The 12-page photographic essay of Callen’s work, gripped readers, who saw the difficult terrain the nurse and midwife was operating in, as well as, the poverty, which clothed the people.

Readers quickly donated more than $20,000 to support Callen’s work in Pineville. The fund was used to open the Maude E. Callen Clinic in 1953, which she ran until her retirement from public health duties in 1971.

Callen began a lecture series in 1926 and later organized a two-week program to train women on basic medical practices. Once a student completed the program she received a license and a uniform, which gave the women a sense of accomplishment and pride.

In 1936, Callen joined the Berkeley County Health Department as a public health nurse. Her job included training midwives throughout the county. She taught young black women the proper practices in prenatal care, labor support, baby delivery, and handling of newborns.

“Her duties included vaccinations, examinations, and keeping records on the children’s eyes and teeth.”

Callen worked as a nurse and midwife in Berkeley County for over 60 years. She was born on November 8, 1898 to Harrison and Amanda Daniel.

She had 12 sisters, had her primary education at the Saint Michael’s and All Angels Parochial Schools in addition to being a graduate of the Georgia Infirmary in 1921. Her devotion to nursing in some of the most poverty-stricken areas in the southern United States was exceptional. She married William Dewer Callen in 1921.

“Nurse Maude recalled that there were only two cars in Berkeley County and none of the roads were paved. Many of her patients arrived at her home in oxcarts in the middle of the night,” she also “frequently had to park her car and walk through mud, woods, and creeks to reach her patients.” It underlines her devotion to her people.

In 1943, Callen’s six-month course at the Maternity Center at the Tuskegee Institute enabled her receive training almost as advanced as a doctor’s. On the back of this, Callen became the second nurse-midwife in South Carolina.

After her retirement in 1971, Callen petitioned county officials to start a Senior Citizens Nutrition Site, which operated, starting in 1980, out of the clinic. As a volunteer, Callen managed the center, which cooked and delivered meals five days a week and provided car service to seniors needing transportation.

She is said to have turned down an invitation from President Reagan to visit the White House noting, “You can’t just call me up and ask me to be somewhere. I’ve got to do my job.”

She taught children how to read and write and held vaccination clinics at local schools for smallpox and diphtheria (one of these clinics inoculated fifteen hundred children). Callen also collected and distributed clothing and helped transport the very sick to the few hospitals that would treat African-American patients. She developed clinics to help families maintain proper nutrition and held the county’s first venereal-disease clinic.

During the Depression, Callen worked with only church and community support. She earned an honorary doctorate from Clemson University and induction into the South Carolina Hall of Fame. She was also honored as the outstanding Older South Carolinian by the State Commission on Aging and was presented with the Order of the Palmetto by then Governor Richard W. Riley.

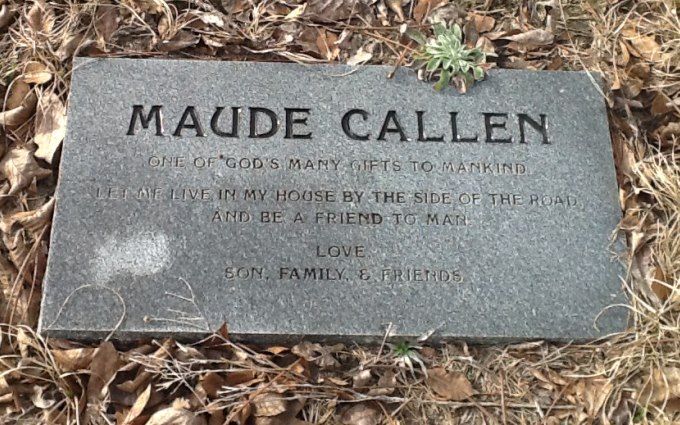

Maude E. Callen died at her home in Pineville on January 25, 1990, and was buried in White Cemetery, near St. Stephen.