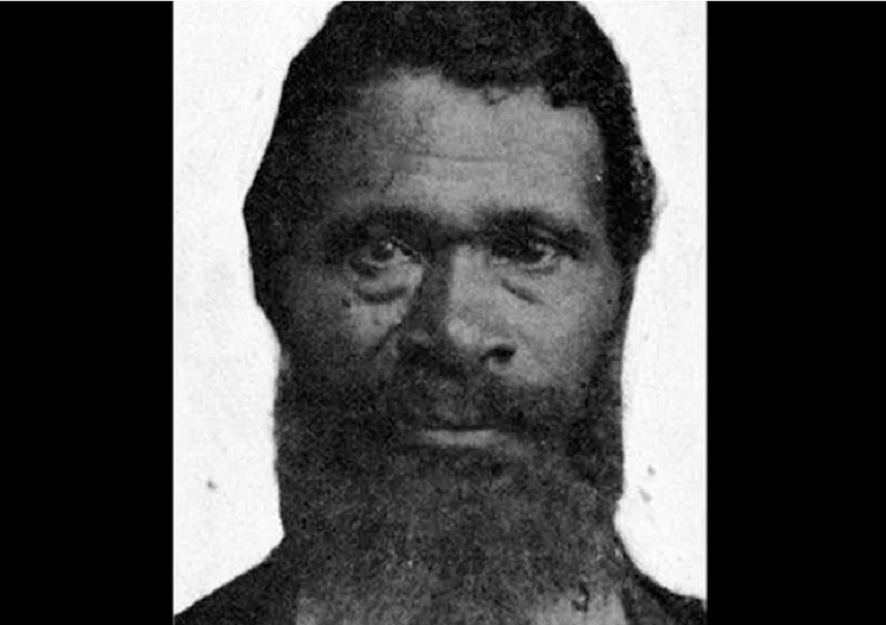

By the 1860s a good number of enslaved African-Americans were coming to freedom on the heels of the conclusion of the civil war. Jordan Anderson also tasted freedom with his wife and children.

So when his former master, who was cruel to him wrote a letter to his new employer requesting his return to the Tennessee plantation as it was in disarray because of the war, Anderson’s letter was sure to be scathing but what many didn’t expect was for it to be rich in humor, biting and afford the world a distillation of Anderson’s thought.

One could feel Anderson’s pain as when just a babe of eight he was sold into slavery in 1825 becoming a servant of the Anderson family for a whopping 39 years without pay.

Things took on an interesting turn for Anderson when the Union Army camped out on the Anderson plantation in 1864. They freed him and his wife, Amanda. The couple journeyed to Dayton, Ohio and settled in with employer Valentine Winters. It was here that in July 1865, he received the letter from his former owner Colonel P.H. Anderson.

On Aug. 7, 1865, Anderson dictated his response through Mr. Winters who was also an abolitionist. The letter found fame when he caused it to be published in the Cincinnati Commercial.

Entitled “Letter from a Freedman to His Old Master,” the letter warmed its way into more hearts and minds when it was republished in the New York Daily Tribune and Lydia Marie Child’s “The Freedman’s Book.”

Anderson was born in December 1825 and had gone pretty much unnoticed till he dictated his letter described as a rare example of documented “slave humor” of the period and its deadpan style has been compared to the satire of Mark Twain.

“The Tennessee native was sold as a slave to General Paulding Anderson of Big Spring in Wilson County, Tennessee, and subsequently passed to the general’s son Patrick Henry Anderson, probably as a personal servant and playmate as the two were of similar age. In 1848, Jordan Anderson married Amanda (Mandy) McGregor. The two eventually would have 11 children together.

“After gaining freedom in in 1864, he may have worked at the Cumberland Military Hospital in Nashville before eventually settling in Dayton, Ohio, moving with the help of the surgeon in charge of the hospital, Dr. Clarke McDermont working as a servant, janitor, coachman, or hostler, until 1894, when he became a sexton, probably at the Wesleyan Methodist Church; a position he held until his death. His employer, Valentine Winters, was father-in-law to McDermont.”

In the letter, Anderson describes his better life in Ohio, and asks his former master to prove his goodwill by paying the back wages he and his wife are owed for many years of slave labor, a total of 52 years combined. He asks if his daughters will be safe and able to have an education, since they are “good-looking girls” and Anderson would rather die “than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters… how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine.” The letter concludes: “Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.”

Colonel Anderson, having failed to attract his former slaves back, sold the land for a pittance to try to get out of debt. Two years later he was dead at the age of 44. Prior to 2006, historian Raymond Winbush tracked down the living relatives of the Colonel in Big Spring, reporting that they “are still angry at Jordan for not coming back.” It was harvest time and there were no hands to bring in the crops.

Anderson died in Dayton on April 15, 1907, of “exhaustion” at 81, and was buried in Woodland Cemetery, one of the oldest “garden” cemeteries in the United States. Amanda died April 12, 1913.