A supposed Africa-themed party held in the grounds of a colonial museum in Belgium has sparked anger after patrons dressed in pith helmets and blackface.

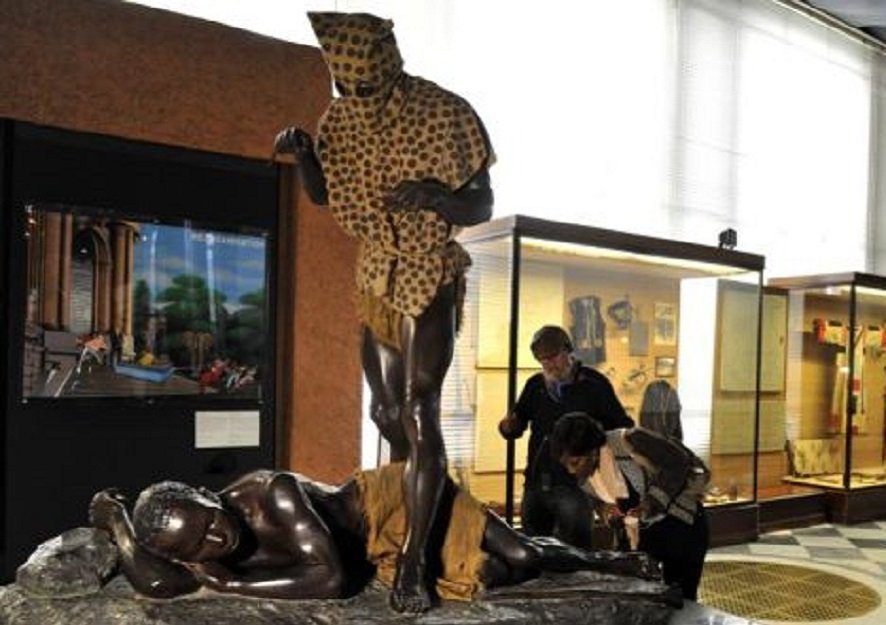

Described as the last colonial museum in the world, the Royal Museum for Central Africa celebrated the Belgians and their brutal history in the Congo under Leopold II, who ruled Congo with an iron fist for more than a century.

The museum, with a large collection of colonial objects, is sited near the former royal estate of Leopold II where he set up the infamous human zoo.

About 2,000 people, on Sunday, attended an open-air party organised by company Thé Dansant to celebrate its tenth anniversary, and involved guests being invited to dress in “African” style to match the theme of the event.

Photos from the event showed some of the patrons dressed in leopard skin print, pith helmets as colonial-era explorers and one man in blackface.

These images have since not gone down well with many people, including the Congolese community groups in Belgium, reports The Telegraph.

Café Congo, an artistic collective involved in reflection on Belgian-Congo relations, hit hard at the organisers for organizing such an event.

“Explain to me how this sort of event – Thé Dansant – can continue to exist in 2019 at the Africa Museum.

“Ethnic, exotic or African is not a costume that you can put on and take off,” Emma Lee Amponsah of the Café Congo organisation told the Bruzz newspaper.

She also condemned the organisers for a stage with skulls on sticks which she argued evoke voodoo and cannibalism. “In this way, stereotypes are constantly being maintained,” she said.

Primrose Ntumba, a museum spokeswoman, said her outfit could not do anything to halt the event because it did not manage the grounds.

“I think it is very unfortunate that Thé Dansant does not see that an ‘African fancy dress party’ can cause angry reactions, and all the more so at this location,” she said.

The theme of the event was simply as “African”, according to one of the organisers, Kjell Materman.

“People are free to interpret that as they will. We asked them to dress colourfully and to use African prints…Even if one person painted his face black, it was not meant to be offensive. Many people of African origin were enthusiastic about the concept and were present,” Materman said.

The Royal Museum for Central Africa, initially called the Museum of the Congo, was closed down for renovations in 2013 and reopened recently as Belgium comes to terms with its colonial past.

In 1958, a group of Congolese men, women, and children were bundled to Brussels, Belgium for a World’s Fair that featured a Congolese Village.

The exhibition called the Kongorama was a way for Belgium to show its connection with the Congo (now DR Congo). It displayed items under various themes including arts and culture, in which the Congolese natives were featured.

Dressed in ‘traditional’ attire and carrying on their daily duties, these men, women, and children were often ridiculed by the spectators day in day out.

Apparently, the Belgian government brought these Congolese natives to be staff at the fair, only for them to end up on display. They were also unfairly treated: placed in a dedicated building where they were transported to and from the fair and restricted from leaving the building.

The colonial office was apparently nervous about what they could do if let loose, the Guardian reported.

It was, therefore, no surprise that this display closed down after the Congolese got fed up with the unfair treatment and decided to head back home. The rest of the fair continued.

This marked the last of the human zoos that had become a popular spectacle in European and American cities at the time.

But before this, King Leopold II had, in 1897, set up a human zoo around his palace in Tervuren in Brussels.

This site is currently the location of the Royal Museum for Central Africa which still contains colonial-era images including more than 180,000 looted items and 500 stuffed animals slaughtered by hunters.

Recently, a UN working group said it is unfortunate that Belgian authorities have refused to remove all the offensive and racist images that are still on display in the 1910 building.

The United Nations Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent further expressed concerns over remaining statues of Leopold and monuments to the colonial army that are still on the streets and parks of Brussels.

The group, after carrying out a fact-finding visit to Belgium, said Belgium must recognize the true scope of the violence and injustice of its colonial past in order to tackle the root causes of present-day racism faced by people of African descent.

“We found clear evidence that racial discrimination is endemic in institutions in Belgium. People of African descent face discrimination in the enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights, including diversion from mainstream education into vocational schooling, ‘downgrading’ in employment opportunities and discrimination in the housing market,” Michal Balcerzak, the chairperson of the working group said this February.