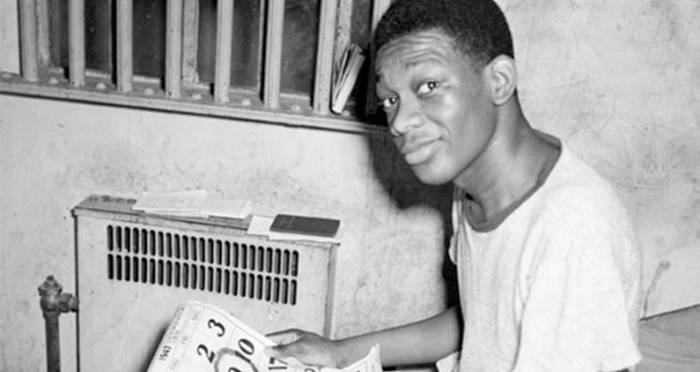

Willie Francis’ case is the first known incident of a failed execution by electrocution in the United States. The stuttering 17-year-old, youngest of 13 children from a poor black family in Louisiana, supposedly murdered a 54-year-old white pharmacist Andrew Thomas in St. Martinville, Louisiana in 1944.

Thomas was murdered in his bed, and when the police failed to make an arrest or even find real leads, Francis, who had once worked for him, was charged with the crime and sentenced to death.

Then the shocking moment arrived. On May 3, 1946, when the 17-year-old was strapped into “Gruesome Gertie,” Louisiana’s electric chair, something went wrong. When the switch was flipped to kill Francis, he began jerking around violently in the chair. That was when officials gathered inside the small parish jail in St. Martinville, La., realized that something had gone wrong – the electrocution was not working.

“Take this off,” Francis’s voice could be heard from beneath the death hood. “I can’t breathe,” he was quoted to have said in a report by NYDailyNews.com.

“You’re not supposed to breathe,” one of the officials replied. But the boy insisted, “I am not dying.” And he was right. Minutes after he was helped out of the chair, reports said that though his heart was beating wildly, he was very much alive.

Francis told reporters, “God fooled with the electric chair.” But perhaps it wasn’t God as it turned out that the “portable” chair, described as a “300-pound monstrosity of oak, leather and wiring” that was transported by truck from jail to jail in Louisiana to perform executions, was not set up properly.

The two in charge of setting it up – Captain Ephie Foster and an inmate named Vincent Venezia who worked as an assistant electrician within the Louisiana prison system were drunk at the time. As they set up the chair, which was attached by cables to electricity generators outside the jail, they improperly grounded the current, among many other errors, and the chair failed to do its job.

Francis later described his ordeal in the chair:

“I wanted to say good-bye, too, (Captain Foster had cheerfully said, “goodbye Willie”, before throwing the switch) but I was so scared I couldn’t talk. My hands were closed tightly. Then—I could almost hear it coming. The best way I can describe it is: Whamm! Zst! It felt like a hundred and a thousand needles and pins were pricking in me all over and my left leg felt like somebody was cutting it with a razor blade.

“I could feel my arms jumping at my sides and I guess my whole body must have jumped straight out. I couldn’t stop the jumping. If that was tickling it was sure a funny kind (He had been told it would tickle and then he’d die). I thought for a minute I was going to knock the chair over. Then I was all right. I thought I was dead. Then they did it again! The same feeling all over. I heard a voice say, “‘Give me some more juice down there!’” And in a little while somebody yelled, ‘”I’m giving you all I got now!”

“I think I must have hollered for them to stop. They say I said, “Take it off! Take it off!’” I know that was certainly what I wanted them to do—turn it off.”

When he was removed from the chair, it is recorded that one of the drunk executioners, Captain Foster, yelled at him, “I missed you this time, but I’ll get you next week if I have to use an iron bar!”

But Francis wasn’t executed the next week, instead, he made headlines in Louisiana, and his case even landed at the Supreme Court.

After the botched execution, Francis’ father, Frederick Francis, was clearly not pleased with the legal representation his son had received in his trial. A report by Herald Record said that during his trial, his court-appointed defense attorney changed Francis’ plea from not guilty to guilty without his consent, did not make an opening statement, called no witnesses, raised no objections, and put up no defense.

And when the boy’s execution failed, his father saw it as an opportune moment to approach another lawyer to handle the case. Thus, while the state prepared to try to kill Francis again, Frederick managed to hire the services of Bertrand DeBlanc, a lawyer who had also been a good friend of Thomas before his death.

DeBlanc agreed to fight for Francis in court. He initially did not think the boy might be innocent, but rather felt that: “It’s not humane to make a man go to the chair twice… The state fell down on its job…. It made [Willie] suffer the torture of facing death without completing it… My few critics will soon be dead and buried but the principles involved in this case of freedom from fear of cruel and unusual punishment and that of due process and double jeopardy will live as long as the American flag waves on this continent.”

But looking into the case, he began to have different views on the teenager’s guilt as he gathered that Francis was not initially arrested for the murder of Thomas but rather miles away from where the murder took place for false drug charges and unrelated reasons.

Francis was then visiting one of his sisters in Port Arthur when he was arrested on suspicion of being a drug dealer’s accomplice, according to reports. When the police could not connect him to the drug dealer, they started questioning him about the murder of Thomas after they had allegedly found the murdered pharmacist’s wallet and identification card in Francis’ possession.

With no legal representation at any point during the interrogation, they reportedly pressed him and within minutes, they had a signed confession from Francis for the murder, and a second confession the following day.

Reports said the gun used in the murder wasn’t examined for fingerprints while the bullets found in Thomas’ body were not matched with those from the gun. What is more, the gun and bullets were lost before the trial while in transit to the FBI for analysis. On the night of Thomas’ murder, one of his neighbors also claimed to have seen a car’s headlights in Thomas’ driveway. Francis couldn’t drive but none of these factors were taken into consideration when he was sentenced to death.

With these factors at hand, DeBlanc faced the Louisiana Pardons Board on May 31, 1946, but his arguments couldn’t stop the poor black teenager from getting another date fixed for a second execution.

DeBlanc then took the case to the Supreme Court with the help of J. Skelly Wright, a maritime lawyer in Washington. But things didn’t go as he expected as the nine justices ruled against Francis 5-4, a day after the boy’s eighteenth birthday.

Not giving up, DeBlanc made moves to get Francis a proper trial after he found out that one of Francis’ executioners had been drunk when setting up the electric chair. But Francis was denied a new trial. DeBlanc later told Francis that he would take the case to the Supreme Court again but the boy asked him not to as he didn’t want any more stress, saying “I’m ready to die.”

On May 9, 1947, almost a year after the first execution attempt, Francis found himself in the electric chair again – this time, it was set up correctly. Asked if he had any last words, he replied, “Nothing at all.”

At 12:05 pm, executioners flipped the switch, and Francis was pronounced dead five minutes later. He would later be branded “the teenager who was executed twice.”