Willie McNeeley was driving his car north from Pittsburg on a Sunday evening on August 3, 1941 when he saw a woman on the side of the road. Thinking she was black, McNeely stopped his car. Then he realized that the woman was white.

42-year-old McNeely knew what would befall him if he is seen driving around a white woman. He was aware of the horrific lynchings of black men in East Texas who were accused of assaulting white women at the time.

Sensing danger, especially from white male residents of Pittsburg, he began to drive off, but the white woman begged him to give her a ride.

“From somewhere, there came a wee, small voice whispering: ‘Don’t do it; drive on’,” McNeeley recalled in his Dallas Express account published two months after the castration.

He, however, said in the newspaper account cited by Vice that the woman’s begging “was so touching and she was so convincing that I suppose I became weak and let her ride.”

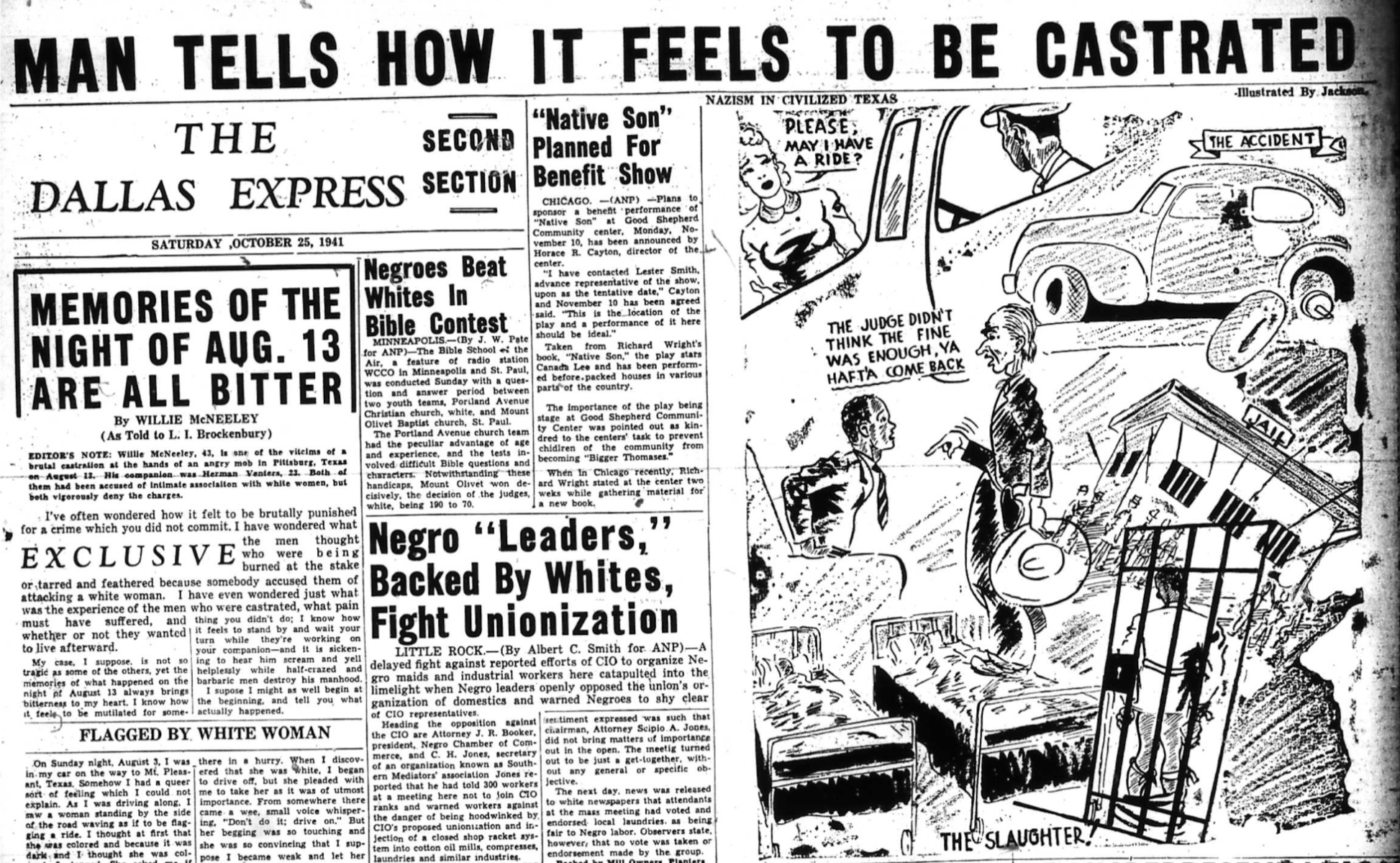

And that was when his troubles began. Moments after giving the woman the ride, one of his tires flew off and he swerved into a ditch. He came out and checked the damage but after a few minutes, a sheriff arrived and dragged him to jail. McNeely spent the night in jail before he was allowed to go.

A week later, in court, the county attorney claimed that McNeely had intended to be “intimate” with the woman. McNeely denied but in the end, he was fined $100 for “vagrancy” and put in a cell with a number of black men.

While in the cell that night, one of the cellmates alerted McNeely to look out the window; a mob of white men, with handkerchiefs covering their faces, was coming towards them. There and then, some of the younger men in the cell started crying, McNeely recalled in the 1941 newspaper account.

Entering the jail and opening the cell, the mob asked McNeeley and one of his cellmates, 23-year-old Harold Venters, to step forward. McNeely later narrated that the men “told me to stand over in the corner with my face to the wall while they began working on Venters.”

After castrating Venters, the men moved to McNeeley.

“Somebody put a hat over my face, and then began the worst ordeal, the worst pain, that I have ever experienced,” McNeeley said.

McNeely had indicated during his trial that never in his life had he entertained the thought of being intimate with a white woman. He knew of the stories of the about 300 black people who were lynched in Texas between 1877 and 1950, including 19-year-old Ed Lang in Rice in 1916 and Lemuel Walters in Longview in 1919.

In the late 19th Century, lynchings were the only latest form of racial terrorism against black Americans after white plantation owners had used various forms of violence against the enslaved.

According to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), tension had begun brewing throughout the late 19th Century in the U.S., and this was mostly felt in the south, where people blamed their financial woes on the newly freed slaves that lived among them.

Whites resorted to lynching as a form of retaliation towards the freed blacks. What mostly triggered these lynchings were claims of petty crime, rape, or any alleged sexual contact between black men and white women. Whites started lynching because they felt it was crucial to protect white women.

“People took pride in responding to this ‘menace of black criminality’ by meeting it with extraordinary barbarity. There are accounts of people who would be castrated and then hung and then shot a thousand times. Everybody wanted to shoot the dangling bodies so they could say that they had participated in the killing of that person,” Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative was quoted by Washington Post.

From 1882-1968, 4,743 lynchings occurred in the United States. Of these people that were lynched, 3,446 were black. The blacks lynched accounted for 72.7% of the people lynched, according to the NAACP, which was quick to add that not all of the lynchings were ever recorded.

Out of the 4,743 people lynched, only 1,297 white people were lynched, that is, 27.3%. These whites were lynched for domestic crimes, helping the black or being against lynching.