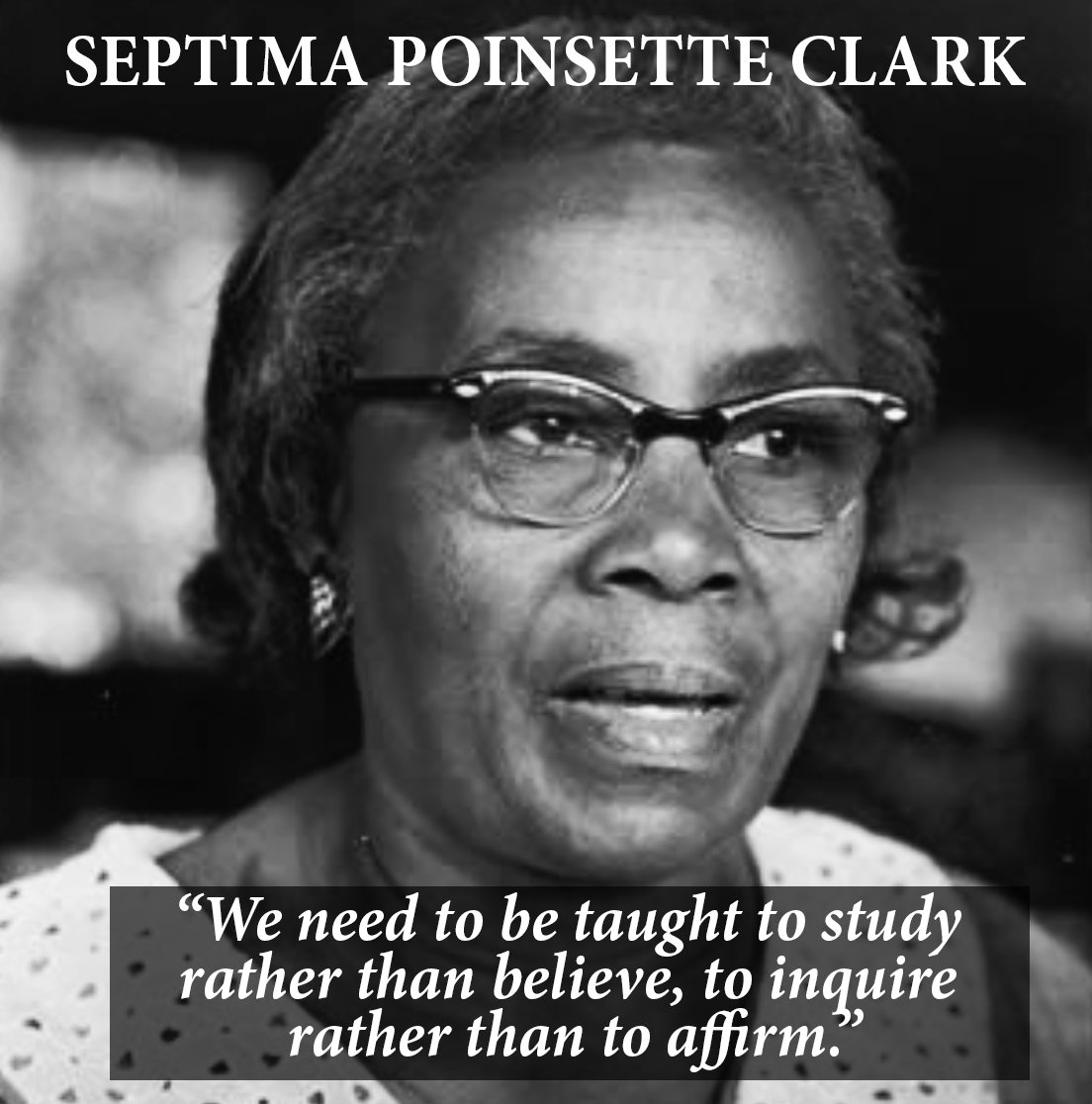

Septima Poinsette Clark could have just resolved to be an elementary school teacher, but she pushed harder by bringing education to the struggle for civil rights.

The daughter of a slave, Clark became known as the “queen mother” of the American Civil Rights movement due to her pioneering work over the years, including her citizenship schools that helped enfranchise and empower African Americans.

Among the many black influential leaders who would benefit from her classes was Rosa Parks, who eventually launched the Montgomery bus boycott that played a huge role in the civil rights struggle.

Despite being perhaps the only woman to play a significant role in educating African Americans for full citizenship rights, Clark has not gained much praise.

Born on May 3, 1898 in Charleston, South Carolina, Clark was one of eight children of a laundrywoman and a former slave. Her parents placed a lot of importance on education, so it’s not surprising that Clark would grow to become a teacher.

But when she received her teaching license, she found out that she would not be able to teach any child, whether black or white, in her native Charleston due to segregation.

Essentially, black teachers were not allowed to teach any student in South Carolina’s capital so Clark had to begin her teaching profession outside of Charleston – on John’s Island.

She returned to her hometown Charleston after joining the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1919. She subsequently visited homes of black parents, collecting signatures of those who wanted black teachers to teach their children in Charleston schools.

Two-thirds of the city’s black population signed the petition and just a year after, the city overturned its ban on black teachers.

But Clark didn’t end there. Alongside the NAACP, she agitated for equal pay for black and white teachers in South Carolina despite the huge opposition to the NAACP at the time.

As a matter of fact, in 1956, South Carolina passed a statute that prohibited city and state employees from belonging to civil rights organizations, including the NAACP. Clark refused to resign from the NAACP, and this made her lose her teaching job of 40 years as her contract was not renewed.

But years before getting fired, Clark had already begun some literacy classes in a school in Tennessee. Clark taught black people “basic literacy skills, their rights and duties as U.S. citizens, and how to fill out voter registration forms,” writes The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.

Parks would attend one of her workshops in 1955.

But officials in Tennessee closed down the school in 1961 and even arrested teachers, including Clark. When she was released, civil rights icon Martin Luther King, Jr., invited her to start a “Citizenship school” in Georgia, similar to the literacy classes she held in Tennessee.

By 1970, she had begun conducting workshops for the American Field Service and eventually got her teacher’s pension reinstated after authorities found that she had been unjustly fired in 1956.

Before her death in 1987, Clark, who also came to be known as the “grandmother” of the civil rights movement, was given a Living Legacy Award by President Jimmy Carter in 1979. She also published her second memoir, Ready from Within, in 1986.

“Through the years, Gyant and Atwater wrote, Clark gained a reputation as truthful, calm, and optimistic. She also had something else in her arsenal: a ‘persuasive speaking ability’ that helped her not only resist oppression within her community, but helped encourage her peers to agitate for change. She did so despite losing her job, facing jail time, and sometimes being silenced by the male-dominated movement,” writes daily.jstor.org.