Marie-Joseph Angelique was considered a rebel slave. Her owner, a French woman in Montreal called Thérèse de Couagne de Francheville, had refused to give her freedom and thus she reigned terror in the household.

When the merchant houses were burnt down, all fingers pointed to Angelique, with her quest from freedom from her bondage used as basis of her trial.

Angelique was born in Madeira, Portugal around 1705. Not much is known about her childhood, but it is believed she was enslaved in her home town. In her early teens, she was sold to Nichus Block, a Flemish merchant and transported to North America, where she was purchased by François Poulin de Francheville at the age of 20.

She was a domestic slave at Francheville’s hometown of Montreal and when he died, her ownership transferred to his widow, Therese, who is credited with naming her ‘Angelique’ after her own daughter, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia.

For the nine years she stayed at the Francheville house, Angelique gave birth to three children fathered by a Madagascar-born slave, Jacques César. None of the children survived infancy. Angelique also had a lover, an indentured white labourer known as Claude Thibault, who is believed to have helped her set fire to the merchant houses.

In 1733, Angelique asked Therese for her freedom but the latter refused, sending Angelique into rage. According to Afua Cooper’s The Hanging of Angelique, she not only made life hard for fellow enslaved woman but also threatened to kill Therese.

Therese sold Angelique in 1734 to one François-Étienne Cugnet of Québec City and was waiting for the ice to thaw over the river so Angelique could leave by boat. Upon hearing of the sale and rumours that she would be shipped off to the West Indies, Angelique threatened to burn down Therese’s house with her in it.

Angelique and her lover Thibault decided to run away. Her aim was to go back to France. However, they were captured near Chambly; Angelique was sent back to Therese and Thibault to jail.

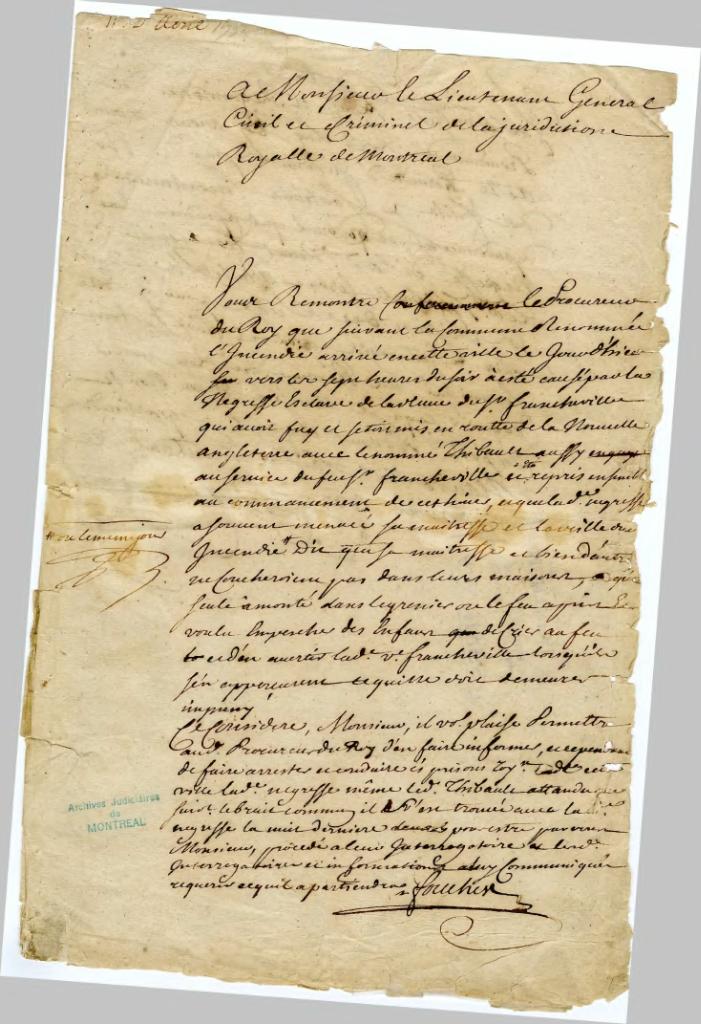

On April 10, 1734, at least 46 merchant houses in Montreal burnt down. The following day, Angelique was arrested, accused of arson. As per the law in the French colony in the 18th century, an accused person was already considered guilty and tried under public inquisitions, which meant that Angelique could not prove her innocence. Worse: France had abolished lawyers in colonies, so she could not be represented.

Angelique was just 29 years old when she was brought before Montreal judge Pierre Raimbault, king procurator, François Foucher, king’s scribe Claude-Cyprien-Jacques Porlier and four notaries. Twenty-four witnesses were called in, 23 of whom accused Angelique on the basis that she told them she would start the fire. Among these was Therese’s five-year old niece.

The 24th witness claimed that she saw Angelique “carrying a pot of live coals up to the roof minutes before the fire started,” and the court based the arson on Angelique’s desire to flee and cover her tracks.

In just six weeks, Angelique was found guilty and sentenced to death. As per the sentence, her hands were to be cut off before she was burned alive. She made an appeal to a superior court in Quebec, only for the court to uphold the death sentence but instead of being burnt alive, she would be tortured, hanged, and then her body burned.

All through the trial in both courts, Angelique maintained that she did not start the fire.

On June 20, 1734, Angelique was tortured using the medieval device called brodequins, which crushed her legs. She confessed to the arson but refused to name Thibault as an accomplice. Later, dressed in white and with a torch in her hand, Angelique was placed in a garbage cart and taken to the

Notre-Dame Basilica. She confessed her crime and sought forgiveness from God, the king and the people.

After Angelique was hanged, her body was displayed on the gibbet for two hours before it was burnt and her ashes scattered to the four winds.

Until today, it is really not known whether Angelique committed the arson. One thing for sure is that she became a symbol of resistance in a society that turned a blind eye to the atrocities of slavery happening right before them.

Angelique’s story was buried in Canadian history, which preferred to showcase its role in the Underground Railway rather than the real state of slavery in the country. It took the discovery of documents detailing this dark part of history for Angelique’s story to be told.