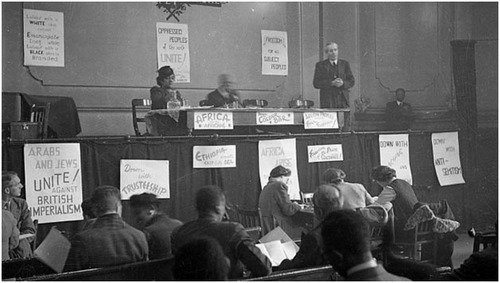

In February 1919, history was made and the Pan-African dream along with its initiative was set in stone at the first Pan-African Congress which brought together 57 delegates from 15 countries.

The meeting, which was the first of five, was held in Paris and was organised successfully by W.E.B Du Bois with the support of Ida Gibbs Hunt who was the wife of the U.S. Consul Willam Henry Hunt working at the American Consulate in France at the time.

The Pan-African Congress was born out of the Pan-African Conference which was held in July 1900 organised by Henry Sylvester Williams with great support from Du Bois. The three-day event brought together 57 leaders and activist across Africa, England, America and the West Indies, serving as a common ground for the start of a conversation on Africa and its future. From this conference began the widespread use of the word Pan-African, its course and objectives especially in Africa.

Unfortunately for Du Bois, Williams and several other interested Pan Africanists faced several challenges while trying to keep the Pan-African dream alive. Racism, travel issues for blacks and the civil war disrupted their meetings and the possibility of another meeting soon after the 1900 Conference.

The main focus of the 1919 Pan-African Congress meeting was to petition the January Paris Peace Conference that had met to discuss the World War 1 and prevent another World War from happening. The Paris Peace Conference had only one black representative, Lecba Eliezer Cadet, a Haitian voodoo priest who was attended on behalf of the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

The Pan African Congress met a month later to demonstrate the existence of black leaders and discuss the black community’s role in the War. Other aims of the Congress meeting was to discuss and put into action the gradual decolonization of Africa, to see to it that Africa is granted home rule with Africans governing their countries as fast as their development permits until at some specified time in the future.

The 57 present delegates presented a very small number of the expected number of delegates. Unfortunately, several others could not make it to Paris due to the fact they were denied visas to travel for the Congress from America and the United Kingdom. Several

The Congress hosted notable Pan-Africanists such as: