Uganda has confirmed it is finalizing an arrangement with the United States to accept deported migrants, provided they are not unaccompanied minors and have no criminal records, according to a statement issued by the foreign ministry on Thursday.

Officials acknowledged that while the deal had been agreed in principle, some terms were still under negotiation. Uganda also signaled a preference for migrants of African origin but did not disclose what incentives, if any, it would receive in exchange for hosting them.

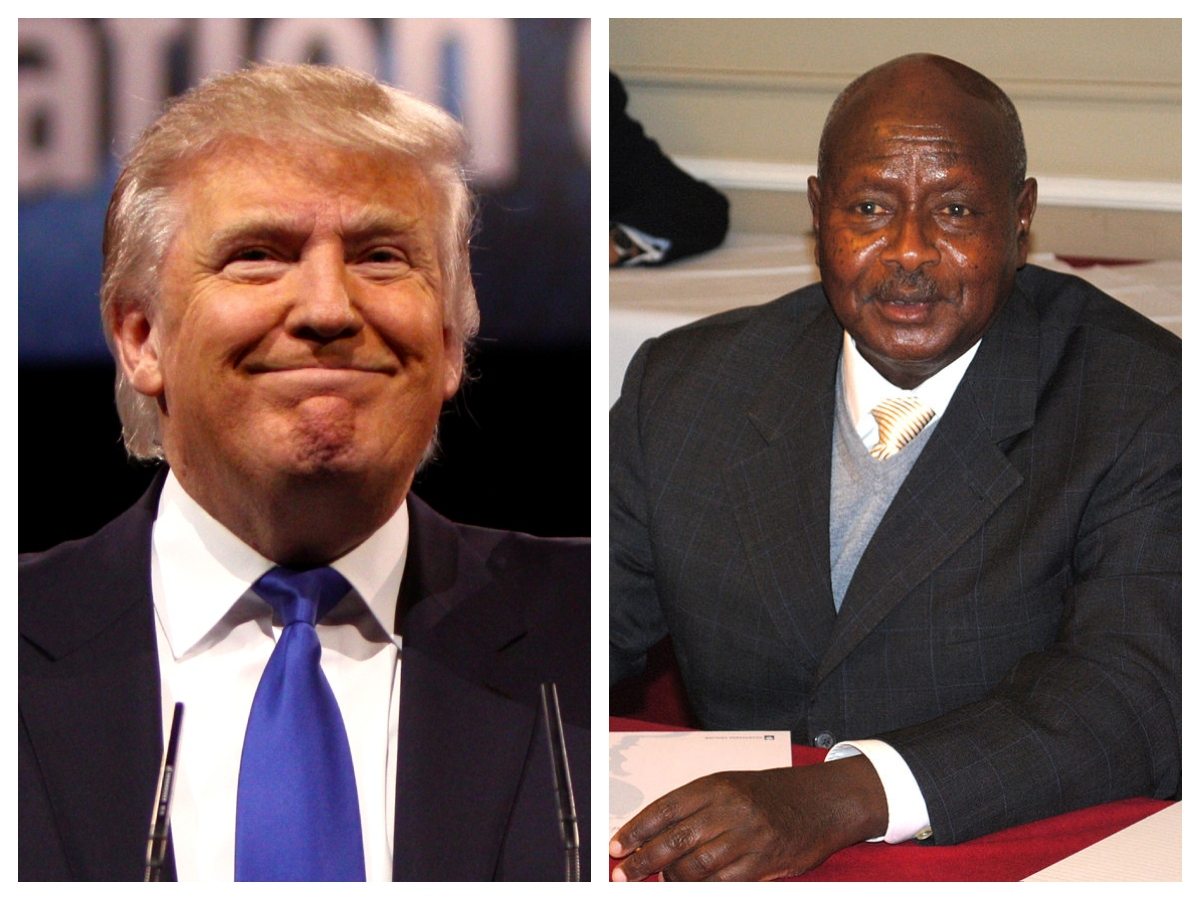

In Washington, the State Department revealed that Secretary of State Marco Rubio recently spoke by phone with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni. Their discussion, according to the department, covered “migration, reciprocal trade, and commercial ties,” with Rubio also commending Uganda for its peacekeeping role in East Africa. The U.S. Embassy in Kampala, however, described the talks only as “diplomatic negotiations” and stressed that the Trump administration’s guiding policy remains “keeping Americans safe.”

READ ALSO: Deported immigrants held in solitary in Eswatini under U.S. third-country policy

The deportation arrangement forms part of the administration’s broader strategy to deter illegal entry and remove migrants who have already crossed into the U.S., especially those with criminal histories or no clear destination for repatriation.

Watch a recent episode of The BreakDown podcast below and subscribe to our channel PanaGenius TV for latest episodes.

Yet the plan has drawn strong criticism. Human rights lawyer Nicholas Opio argued that such an arrangement is tantamount to trafficking: “Are they refugees or prisoners? … That I can keep your prisoners if you pay me; how is that different from human trafficking?” Opposition lawmaker Muwada Nkunyingi also denounced the deal, suggesting it was politically motivated. “Uganda’s leaders will rush into a deal to clear their image now that we are heading into the 2026 elections,” he said in an AP report.

Foreign Minister Henry Okello Oryem initially denied any formal agreement earlier this week but acknowledged that talks were underway involving “visas, tariffs, sanctions, and related issues.” He stressed that Uganda would not accept deportees tied to organized crime. “We are talking about cartels: people who are unwanted in their own countries. How can we integrate them into local communities in Uganda?” he asked.

International law concerns are not new in U.S. deportation policy. In July, U.S. sent five men with criminal records to Eswatini and attempted to deport eight more to South Sudan. Those deportations faced legal challenges in the U.S. courts before the Supreme Court ultimately allowed them to proceed.

Relations between Uganda and the United States have been strained in recent years, particularly after Uganda enacted a 2023 anti-homosexuality law imposing harsh penalties, including life imprisonment. The U.S. responded with sanctions on top officials in 2024, while the World Bank withheld some funding.

As negotiations over deportations continue, critics warn that Uganda risks being drawn deeper into the United States’ domestic migration battles, with deportees caught in the middle.