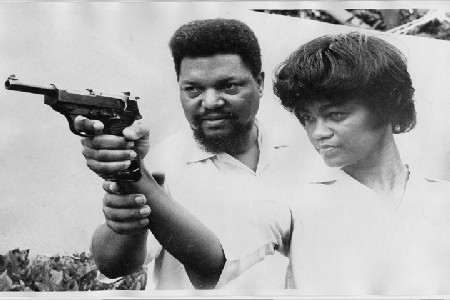

He was a decade or more ahead of the Black Panthers and other blacks who rejected the principle of nonviolence spearheaded by mainstream civil rights movement. Robert F. Williams was the first African American civil rights leader to advocate armed resistance to racial oppression and violence, often vowing to meet ”violence with violence” in the civil rights struggle.

Despite inspiring the movement for “black power” in the late 1960s and helping motivate groups like the Student National Coordinating Committee and the Revolutionary Action Movement, he was criticised by some individuals within the civil rights struggle due to his militant and radical stance.

Born in Monroe, North Carolina, in 1925, Williams was the grandson of former slaves. During World War II, he migrated to Detroit, Michigan where he worked in an auto factory and organized for the United Auto Workers (UAW).

Growing up, Williams learned to adjust quickly to the dangers of being black in the Deep South, especially as the white supremacist group Ku Klux Klan was wreaking havoc against black people in most communities.

Williams grandmother, before she died, gave him what would be his first rifle – a gun that belonged to the family – to serve as a symbol of the family’s resistance against racial oppression, a report by PBS said.

Williams would fight in the race riot in Detroit in 1943 and have a stint in the Marines before returning to Monroe in 1955. In 1956, Williams was elected president of the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

At the time, the local branch of the association was nearing collapse as it had to deal with fierce criticism from the KKK. But Williams eventually brought in new members and increased membership from just 6 to 200 members.

According to BlackPast, Williams built membership in his own image: “working class, militant, and armed—a far cry from the moderate, middle-class make-up of the national organization.”

He filed for a charter from the National Rifle Association (NRA) and formed the Black Guard, an armed group that he physically trained and gave weapons to protect the black population in Monroe.

Williams spearheaded the local civil rights campaigns and highlighted the conditions of the Jim Crow South in both national and international media. He further led the fight to desegregate the local public swimming pool, amidst strong opposition from local whites and the KKK.

The radical civil rights leader would, in 1959, help gain support for gubernatorial pardons for the two young African-American boys who were jailed for kissing a young white girl in what was known as the “Kissing Case” of 1958.

During that period, a jury in Monroe had acquitted a white man for the attempted rape of a black woman. This angered Williams, forcing him to make what has been described as a ‘historic statement’ that would ruin his membership with the NAACP.

“…if the law, if the United States Constitution cannot be enforced in this social jungle called Dixie, it is time that Negroes must defend themselves even if it is necessary to resort to violence.

“That there is no law here, there is no need to take the white attackers to the courts because they will go free and that the federal government is not coming to the aid of people who are oppressed, and it is time for Negro men to stand up and be men and if it is necessary for us to die we must be willing to die. If it is necessary for us to kill we must be willing to kill.”

The NAACP, which felt that Williams incited violence with those words, suspended him. In 1961, the Freedom Riders, an interracial group of activists stormed Monroe to protest against passive resistance which had almost become the trademark of the mainstream civil rights movement.

In the heat of the demonstration, the Riders were attacked by Klansmen, and this forced them to seek help from Williams and his Black Guard.

Williams would shelter a white couple from an African American mob amid the protests, but this would rather cause him to flee Monroe, alongside his family, after he was accused of kidnapping the couple.

Williams and his family took up residence in Cuba as a guest of Fidel Castro. For the next five years in Cuba, Williams went ahead to fight for human rights for black people through his newsletter, The Crusader, as well as, a weekly radio program, “Radio Free Dixie,” that reached thousands of black listeners in the United States.

In 1962, he wrote the book, Negroes With Guns, which would be “the single most important intellectual influence on Huey P. Newton, the founder of the Black Panther Party.”

Williams and his family moved to China in 1966 where he became a friend and advisor to Mao Zedong and other influential personalities. He would, for the next few years, travel throughout Africa and Asia, speaking out against racism and colonialism. In 1968, while in Tanzania, he was named the first president of a black nationalist organization, the Republic of New Africa.

In 1969, Williams returned to the U.S. and all charges against him were later dropped. He separated himself from the Black Power movement partly due to changes in his political disposition and began advising the State Department on its relations with China.

Before his death in 1996 of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Williams was active in the Peoples’ Association for Human Rights in Baldwin, and lectured about civil rights in schools and churches.

At his funeral, activist Rosa Parks praised him for “his courage and for his commitment to freedom”.

She said: “The sacrifices he made, and what he did, should go down in history and never be forgotten.”