By 1865, slavery had become an illegal practice in the United States of America, allowing former slaves to own properties and start lives of their own as long as they, like everybody, adhered to the laws that governed their respective jurisdictions although many of those laws still discriminated largely against the Black race.

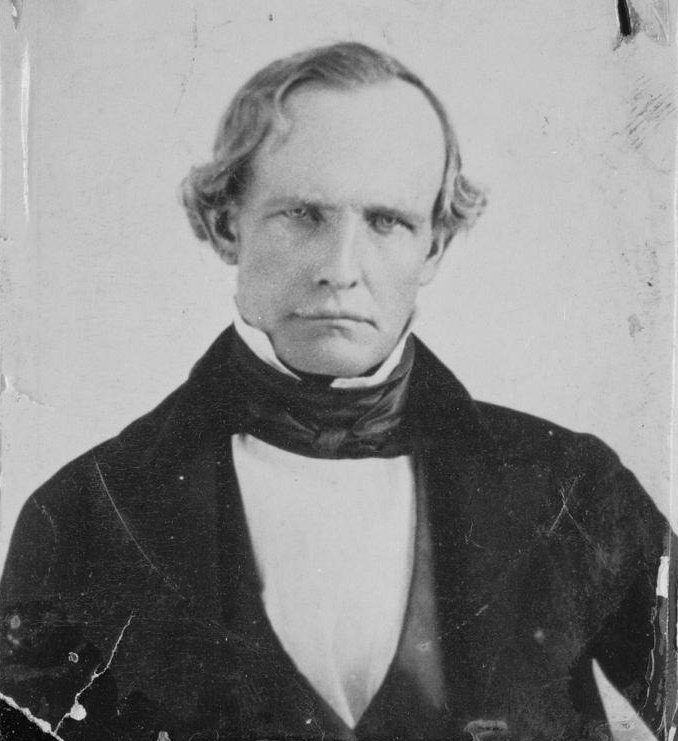

And the same went for many intolerant and completely dogged individuals who still believed that the Black race was a second-class one and should therefore not be allowed to exist on its own. Peter Hardeman Burnett, first Governor of California and a man who rose to the highest law-making body of America, for instance, was one of these people.

Known famously for his many racially-instigated actions, decisions and attempts, this astute, self-taught lawyer of the mid 1800s was a man that, instead of his many stellar accomplishments in academia and in public administration being the focus of his life, is no longer as important.

Burnett was responsible for many racist decisions against the Black race of including the “Lash Law” of Oregon which is today famously known as the “Peter Burnett ‘s Lash Law.”

This exclusion law against African-Americans sort to achieve this one goal: Blacks in Oregon – be they free or slave, man or woman – be whipped twice a year (up to 39 lashed) “until he or she shall quit the territory.”

The law, which undermined an earlier provisional government ban on slavery entirely, also allowed slave owners three years to free enslaved persons, in effect legalizing slavery for three years. Although the whipping penalty was soon changed, and possibly never executed, it is probably the one thing anyone in Oregon knows about Burnett today, if they know anything about him at all.

Born in Nashville, Tennessee, on November 15, 1807; his mother was a member of the prominent Thomas Hardeman family, but Burnett said his parents struggled to make a living and he grew up poor. That, if it was the case, did not create any sense of sympathy in him, rather, it fueled his life-long disgust for the African-American race, pushing him off the plate of those who should be celebrated today for major things they did for humanity and the Black race in their time.

As a young boy, Burnett had two slaves dedicated to him in Missouri, according to an 1840 census, largely so too because on both sides of his family, they owned enslaved persons. Indeed, it is believed that he may have tried to bring at least one enslaved person to Oregon, as accounts of the 1843 emigration refer to a young African-American woman, or girl, who drowned in the Columbia River, as being attached to the Burnett family.

A man known to have had probably the most impressive list of achievements of any leader in the early American West, going on to serve on the supreme court of the Oregon Territory and becoming the first governor of California, Burnett’s legacy today is shrouded in a lot of failed attempts by what is described as blatant racism and inept leadership.

He made questionable decisions that undermined his leadership, including changing the 1850 Thanksgiving Observance from a Thursday to a Saturday, evidently for his own convenience.

He was also responsible for notoriously trying severally to push down his racist ideologies about Blacks and why they didn’t need to be freed totally. In California for instance, Burnett joined a heated and divisive debate over race and slavery that extended throughout the states and territories and was tearing the nation apart, culminating in the Civil War.

Several delegates to the 1849 Constitutional Convention were slave owners, among them William McKendree Gwin—soon to be chosen as one of California’s first U.S. senators—who owned at least 200 enslaved persons on his Mississippi plantation.

With little debate, the delegates voted to prohibit slavery in the soon-to-be new state, but they deliberated at length as to whether to include a provision in the constitution banning African Americans, before finally deciding that it would be improper to include such a law in the constitution. They did deny blacks the right to vote.

Once elected to the supreme court in California, Burnett picked up the torch for exclusion in his first annual message to the Legislature, calling the exclusion an issue of “the first importance.” He used the same racist arguments he had used in Oregon: African Americans would take jobs from whites, and would be a discontented element in society because they were second-class citizens deprived of the same rights as the white population.

To this, he added a prediction that manumitted slaves from the South would be “brought to California in great numbers.” As many as 1,000 blacks, both free and enslaved, were already in California, working in mining camps and at other jobs.

His insistence and fears on getting Blacks out was unrelenting, as he believed banning African Americans would produce the greatest good for the greatest number. “We have certainly the right to prevent any class of population from settling in our state that we may deem injurious to our own society . . . ” He mocked anyone who opposed such a law as succumbing to “weak and sickly sympathy.”

But his dislike for race, and especially the Black race was not a thing that only begun in California. As a young store owner in Clear Creek, Tennessee, he was responsible for killing an enslaved black man who broke into his store to drink from his whiskey barrel. Burnett set a trap for the burglar by propping a rifle on the counter with a string from the trigger to a window shutter. He went home to sleep and the next morning found the man dead on the floor. Burnett expressed remorse and was not charged with a crime.

In 1851, Burnett was back at it, again calling for an exclusion law requiring that Blacks be slapped with even harsher terms than before. “They have no ideas and no recollections of a separate national existence—no alliance with great names of families—no page of history upon which they recorded the glorious deeds of the past—no present privileges—and no hope for the future,” he said.

Unsurprisingly, Burnett didn’t stop with blacks. He also predicted a war of extermination against the Native American tribes. He would later argue in favor of prohibiting Chinese immigration, writing in his autobiography, Recollections and Opinions of an Old Pioneer, that enterprising and hard-working Chinese would eventually dominate the Western economy “to the ultimate exclusion of the white man.” He said their very presence is “making tyrants and lawless ruffians of our boys” who could not resist the temptation to harass them.

Among other extreme things he did, the press during his time hugely condemned him for temporarily approving the death penalty for persons convicted of robbery and major property crimes.

But he achieved quite a lot with his life. He served as Oregon’s first provisional supreme court judge, was appointed to the Territorial Supreme Court, and opened the first wagon road from Oregon to California, leading about 150 would-be miners to California’s gold fields in 1848.

In California, his new home, he worked with John Sutter Jr. to develop the city of Sacramento; served in the pre-statehood San Francisco Legislative Assembly; was elected a judge on the pre-statehood Superior Tribunal; was elected governor following the 1849 Constitutional Convention; served on the Sacramento city council; and was appointed to the California Supreme Court in 1857.

As supreme court judge in California though, he was again undone by his racism. Burnett wrote the majority opinion in a ruling on January 11, 1859 that would have returned a black man, Archy Lee, to slavery in Mississippi even though he had been brought to California by his owner, and therefore by California law presumably was a free man. Lee’s attorneys maneuvered to have the decision ignored, and Archy Lee was freed. But the decision once again subjected Burnett to unbridled criticism.

He died in San Francisco on May 17, 1895 and is a forgotten man today.