During the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, many slaves were sold off against their will; others were also tricked into slavery.

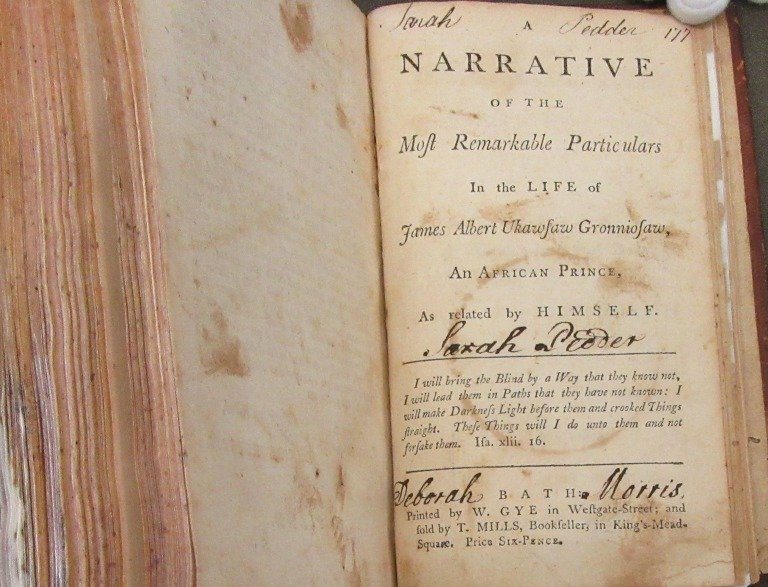

Until 1772 when the first black author published his first book in Britain, people did not really know much about what slavery did to the enslaved. James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw was the first black author who gave an account of his life as a slave and a freed man in his autobiography, A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, An African Prince.

In 1772, the book was first published in Bath. It has undergone some slight modifications over the years and as of 1811, it had about nine editions.

Some have referred to Ukawsaw’s book as a migrant’s tale. It is said to be the first account of what life awaited a black man who migrated to Britain.

In a typical African home, a child does not question elders, especially about things they deem as tradition. A curious child is usually unsure of what their fate would be.

So, for Ukawsaw, the fifteen-year-old grandson of the reigning king of Borno, his curiosity about the “Great man of Power” didn’t sit well with his kin.

A young Ukawsaw, born around 1710 in Bornu, Nigeria, was on a quest to know the power that resides above “our object of worship.”

Some traders visited his village and offered to take him to Gold Coast, now Ghana, to probably seek further answers. The visitors told him he’d “see houses with wings to them walk upon water and white folks in Gold Coast”. He tagged along only to be “tricked” into slavery.

Sold into slavery and clueless as to what could happen to him, Ukawsaw was first taken to Barbados and later sold to Vanhorn in New York. Theodore Frelinghuseyen, an influential minister and friend to evangelical preacher George Whitefield, was in search of a slave. Ukawsaw was given to him due to his upright behaviour on the ship that had thousands of other slaves.

The Frelinghuysens could see Ukawsaw’s interest in religious matters and introduced him to Christianity – Calvinist theology precisely. He worked with the family for twenty years till his master died in 1747. Theodore’s will set him free but Ukawsaw served his widow and children till they also passed on four years later.

Ukawsaw’s thirst for the religious side of life made him want to visit England, where he believed, was the seat of Christianity. He voices “a desire to come to ENGLAND. —I imagined that all the Inhabitants of this Island were Holy; because all those that had visited my Master from thence were good.”

Still viewing England as “the promised land”, he said, “I expected to find nothing but goodness, gentleness and meekness in this Christian Land.” (p. 24)

To advance his religious cause, Ukawsaw enlisted in the British army and served on a ship until he arrived in Britain in 1764. Ukawsaw, having been introduced to the Calvinist theory in America, found himself around the Selina Hastings, the Countess of Huntington and the perceived head of the Calvinists in Britain at the time.

Selina paid for Ukawsaw’s book and enlisted her friends to assist with the narration since he was illiterate at the time. The narration focused more on his conversion to Christianity and his Calvinist encounters than his life as a slave though there were a few pages dedicated to some slave tales.

Most people who patronized the book did not do so to satisfy their curiosity on slaves or the migration of black folks to Britain but rather for its religious connotations.

Migrants at the time faced issues that today’s migrants are still dealing with. Racial prejudice was at the forefront and biracial relationships were and are still not easily accepted by many. Marriage was also a way for a black migrant to cement their roots in Britain. Poverty was another hardship Ukawsaw faced. Some even say he died a poor man at age 70.

Ukawsaw married a white widow in Britain called Betty. Betty was a weaver with one child. Before he could marry Betty, Ukawsaw had to be baptised. Black slaves at the time knew baptism did not guarantee their freedom, yet they still got baptised in their numbers.

Life became unbearable so the couple decided to travel around the country in search of better employment opportunities. Ukawsaw, in his book, describes winters as particularly hard for them. Their state of life made them easy prey for predators.

In Portsmouth, Ukawsaw writes that he is exploited by a woman who “kept a Public-House.” She swindled him out of his money and watch. In the same setting, the woman’s brother comes to his aid and invites him into her home and even promised to help him regain his possessions.

In a village near Norwich, Ukawsaw mentions a friend, Mr Gurdney, who helps him find work. He becomes a target for the locals who found means to challenge and make his life harder than it already was.

Through all his trials, he never wavered in faith. Ukawsaw said he understood all he encountered through “prayer and religion.” He saw his ordeal as a missed opportunity to make more “Christian friends.”

He still chose to be optimistic: “I could scarcely believe it possible that the place where so many eminent Christians had lived and preached could abound with so much wickedness and deceit” (p. 25).

Even though his “Christian friends” did not help him bury his dead child because she was black, his religious lens left him in denial about the motives of the clergymen.

At the close of the narrative, he and his family, due to the unwelcoming environment, eventually moved to Kidderminster from Norwich and his wife Betty, had just had another child.

To Ukawsaw, all his trials from the Gold Coast, through America and then to Britain were all clearing the path for his journey into Heaven. He describes it “as Pilgrims… travelling through many difficulties towards our HEAVENLY HOME” (p. 39)

It is unknown if Ukawsaw made any profit from the sales of his narrative to Selina Hastings, but his family had ‘the sole profits arising from the sale’ of the book.

Ukawsaw draws attention to the racial bias black people experienced in eighteenth-century Britain.

His book was simply a person walking others through his life. Though he was less critical about the slave trade at the time, the book still gives an insight into slavery and religion during his time.

The following is a video of the life of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, played by actor Shango Baku.