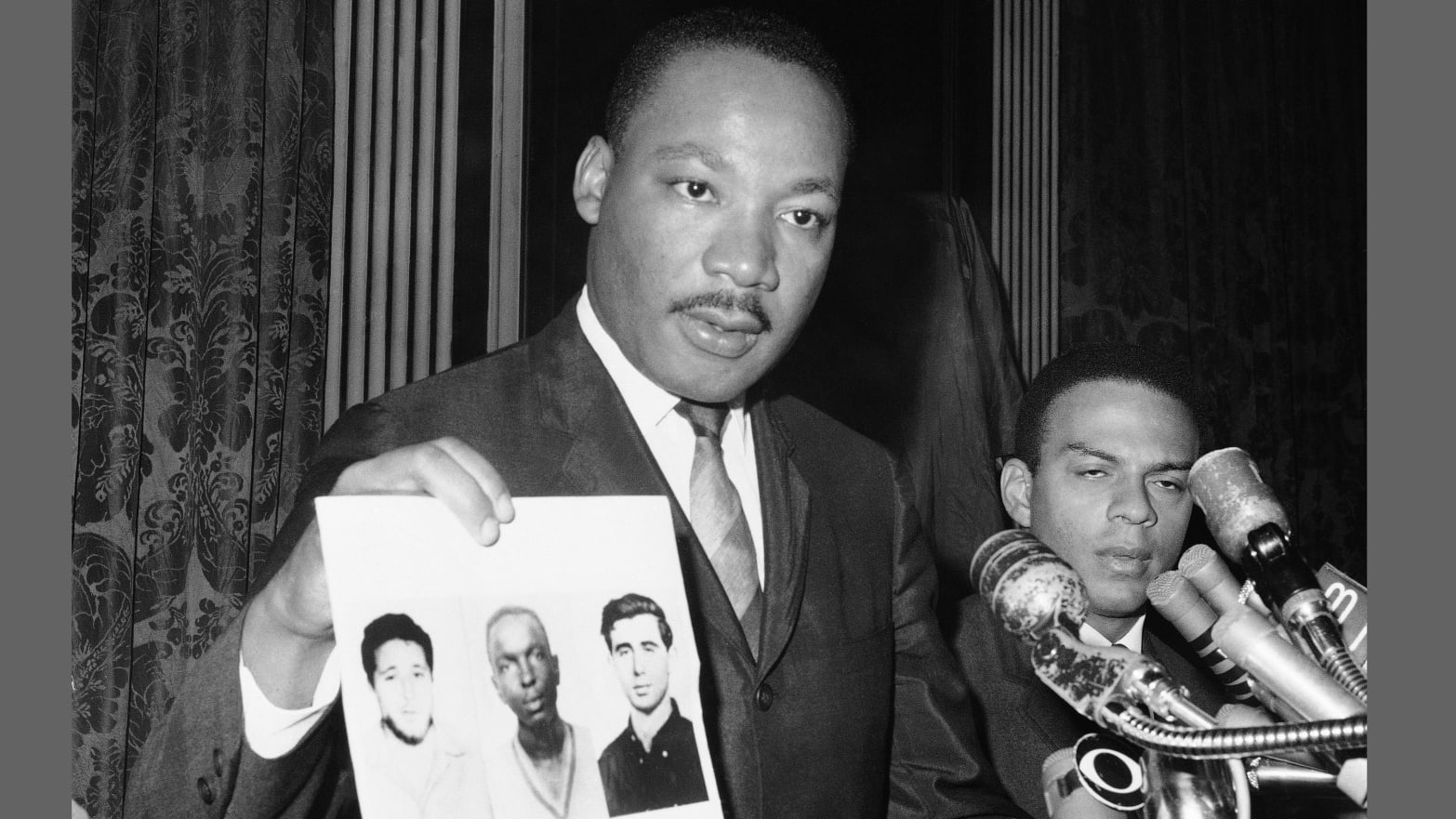

The fight for human rights sometimes called civil rights by Blacks in America was a tough battle as the whites, who enjoyed the privileges sought to keep the racist system going so fought back. It claimed the lives of Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney.

It was a battle of no middle ground, it was either you were for the white privilege or on the frontline through protest marches, boycotts and sometimes violence demanding the right to vote, work, school, own property, marry and even travel without hindrance.

For sympathetic whites who supported the demands of the Blacks, they were viewed as traitors to the white race by the oppressor and such were fair game to be attacked along with the Blacks.

Such whites included students and activists who faced violence and death once they crossed the Mississippi state line.

The first wave of recruits included 20-year-old Andrew Goodman from New York. Goodman rode with civil rights worker James Chaney 21 and Michael Schwerner 24 also from New York.

On Sunday June 21, 1964, the three men drove to investigate the burning of a black Methodist church. The church had been the scene of a civil rights meeting just weeks before.

Around 3pm, that afternoon, their 1963 Blue Ford Falcon Station Wagon was stopped by Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price outside of the town of Philadelphia. All three were associated with the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) and its member organization, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They had been working with the Freedom Summer campaign by attempting to register African-Americans in Mississippi to vote.

Price, a member of the KKK who had been looking out for Schwerner and other civil rights workers, threw them in the Neshoba County jail allegedly for speeding.

The young men comprising a black and two whites were released by Deputy Price around 10:30 pm that night. It was then that they disappeared never to be seen alive again.

In Oxford, Ohio, volunteers were waiting to travel to the south on their volunteerism and civil rights campaign activities.

Bob Moses of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) noted “we had to tell the students what was going on because if anyone was arrested and taken out of jail, then the chances that they are alive is almost zero,” adding the students had to be confronted with the reality before they went down.

Within days, the disappearance was national news. A massive search was ordered by President Lyndon Johnson. 200 sailors from the Naval Air Station in Meridian moved into the Philadelphia area joined by FBI agents.

Michael Schwerner’s wife Rita flew in from Oxford welcome by Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)’s James Farmer. Rita Schwerner was training volunteers back in Ohio.

“it’s tragic as far as I’m concerned that white northerners will be caught up in the machine of injustice and indifference in the south,” adding “had Chaney been alone his disappearance would have been no news”, a fate endured by man other Blacks in the south.

“Their disappearance (Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner) calculated to drive away people from the south put the opposition effect on me and everyone else,” a volunteer submitted stressing that his freedom is tied to the freedom of another so if another man isn’t free, then he is also not free. It is why they are challenging the status quo despite being scared for their lives he added.

Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney were shot to death and their bodies buried in an earthen dam a few miles from the Mt. Zion Methodist Church.

The three men’s bodies were only discovered two months later thanks to a tip-off. During the investigation it emerged that members of the local White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, the Neshoba County Sheriff’s Office and the Philadelphia Police Department were involved in the murders.

After the state government refused to prosecute, in 1967 the United States federal government charged eighteen individuals with civil rights violations. Seven were convicted and received relatively minor sentences for their actions. Outrage over the activists’ disappearances helped gain passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Forty-one years after the murders took place, one perpetrator, Edgar Ray Killen, was charged by the state of Mississippi for his part in the crimes. In 2005 he was convicted of three counts of manslaughter and was serving a 60-year sentence. On June 20, 2016, federal and state authorities officially closed the case and dispensed with the possibility of further prosecution. Killen died in prison in January 2018.