“I leave you a thirst for education. Knowledge is the prime need of the hour.” Those were the words of Mary McLeod Bethune before her death on May 18, 1955.

Born in 1875 to former slaves, Bethune was the 15th of 17 children sired by Sam and Patsy McLeod – the first of her siblings to be born into freedom.

Bethune defied the many systematic obstacles created to hinder the development of the African American to found a college aimed at educating the black generation.

Bethune’s enthusiasm for knowledge was ignited during one of her rounds with her mother.

According to historical narrations, Bethune accompanies her mother to the homes of white people where they would deliver laundry when she was young.

It was reported that during one of those rounds, she picked up a book but as she opened it, a white child took it away from her, saying she didn’t know how to read.

That was when Bethune convinced herself without equivocation that education was the way – the way to rewrite the narrative about African Americans and their contributions to the liberation of America from the clutches of the British as well to the development of a country that’s now regarded the most powerful on planet earth.

According to the National Women’s History Museum (NWHM), Bethune graduated from Scotia Seminary, a boarding school in North Carolina in 1894. Other publications say she graduated in 1893.

“Her parents instilled in her a strong work ethic and they also encouraged her to get an education,” Tasha Lucas-Youmans, Dean of the Carl S. Swisher Library on the Bethune-Cookman campus said. “Census records show she was reading by the time she was 4 years old.”

After Scotia Seminary, Bethune continued to Dwight Moody’s Institute for Home and Foreign Missions in Chicago, Illinois. When no church was willing to sponsor her as a missionary, she opted to become an educator.

After her marriage with fellow teacher Albertus Bethune in 1898, the couple moved to Palatka, Florida. The couple, according to Biography, had one son together – Albert Mcleod Bethune – before ending their marriage in 1907.

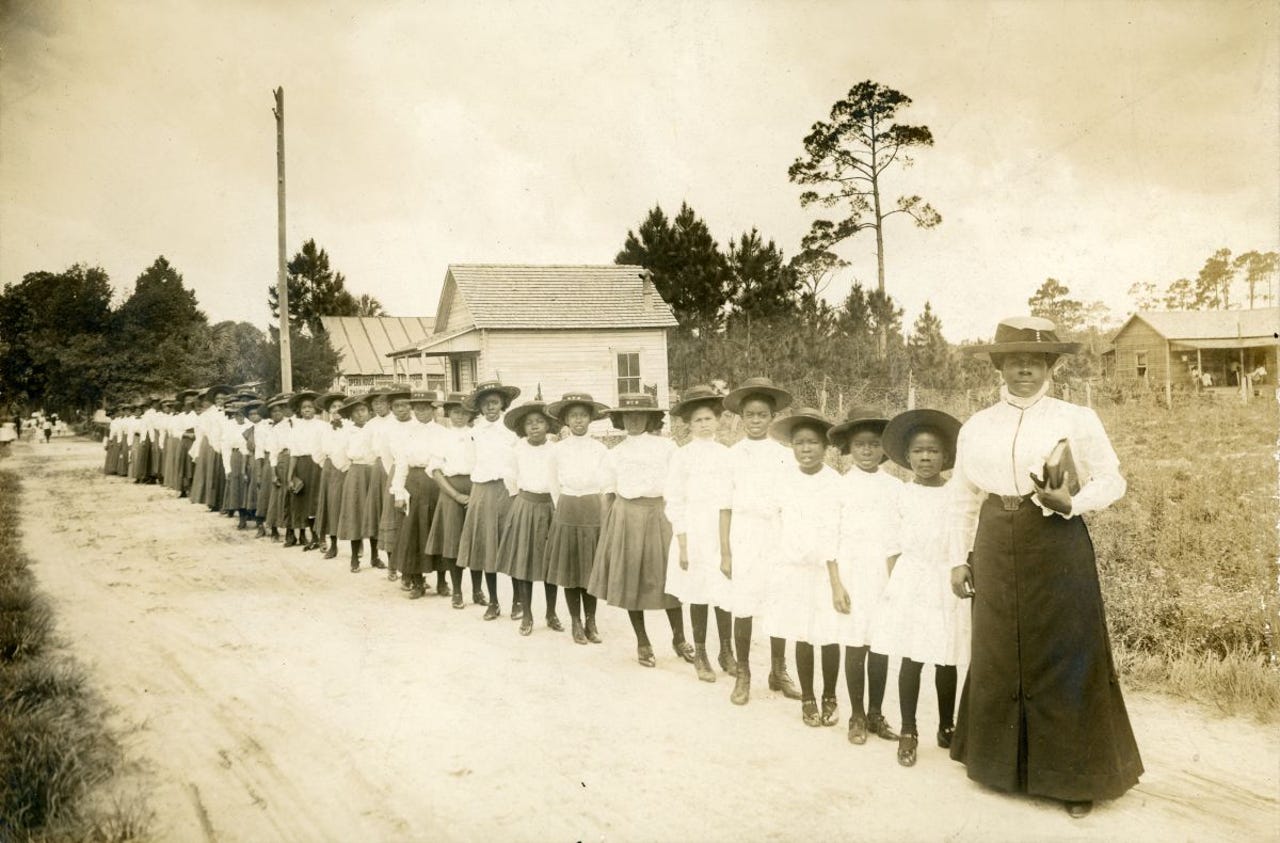

A believer that education provided the key to racial advancement, Bethune founded the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls in Daytona, Florida, in 1904. Starting out with only five students, she helped grow the school to more than 250 students over the next years.

“She had the audacity to go to beachside and be brazen enough to confront these people, a lot of the wealthy white people that would come here for summer vacation, and talk to them and encourage them to help,” Lucas-Youmans said.

“And the fact that they would even listen to this poor little black girl from Mayesville, South Carolina, that said she had a dream that she was going to build a school on a city dump. They did. They believed her.”

According to Tallahassee Democrat, Thomas White of White Sewing Machine and James Gamble of Proctor and Gamble donated money to buy a Victorian-style two-story house for Bethune, which still stands at the northeast corner of the campus in 1914.

The expansion of the Daytona Normal and Industrial Institute for Negro Girls would continue throughout the next decade and in 1923, it merged with the Cookman Institute of Jacksonville and became co-ed while also gaining the United Methodist Church affiliation, Tallahassee Democrat reports.

In 1925, the combined school’s name was changed to Daytona-Cookman Collegiate Institute. The name was officially changed in 1931 to Bethune-Cookman College to reflect its leadership.

Bethune served as the school’s president. It was one of the few places that African-American students could pursue a college degree. Bethune stayed with the college until 1942.

According to the National Women’s History Museum, Bethune, a champion of racial and gender equality, went on to found many organizations and led voter registration drives after women gained the vote in 1920, risking racist attacks.

She was elected president of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs in 1924 and in 1935, she became the founding president of the National Council of Negro Women.

The National Women’s History Museum further reports that Bethune also played a role in the transition of black voters from the Republican Party – “the party of Lincoln” – to the Democratic Party during the Great Depression.

She was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt and in 1936, Bethune became the highest-ranking African-American woman in government when President Franklin Roosevelt named her director of Negro Affairs of the National Youth Administration, where she remained until 1944. She had earlier, in 1936, become a special adviser to President Roosevelt on minority affairs.

In 1937, Bethune organized a conference on the Problems of the Negro and Negro Youth and fought to end discrimination and lynching. In 1940, she became vice president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored Persons (NAACP), a position she held for the rest of her life.

Bethune died on May 18, 1955, in Daytona, Florida.

Honored with many awards, in 1973, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame. Also, the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp with her likeness in 1985. Her burial place is a National Historic Site.