“Don’t get mad — get smart,” Andrew Young’s father, Andrew Sr., once told him, growing up in New Orleans in the midst of racial tensions.

Young would learn not to flare up in anger amid the discrimination but to stay calm and in control of his feelings. “If you lose your temper, you lose the fight,” he recalled recently.

This is how Young has lived his life and been successful in changing history. After graduating from college, Young didn’t know what to pursue in life. During this period, Martin Luther King, Jr had become famous for his role in the 1955 Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott to oppose racial segregation.

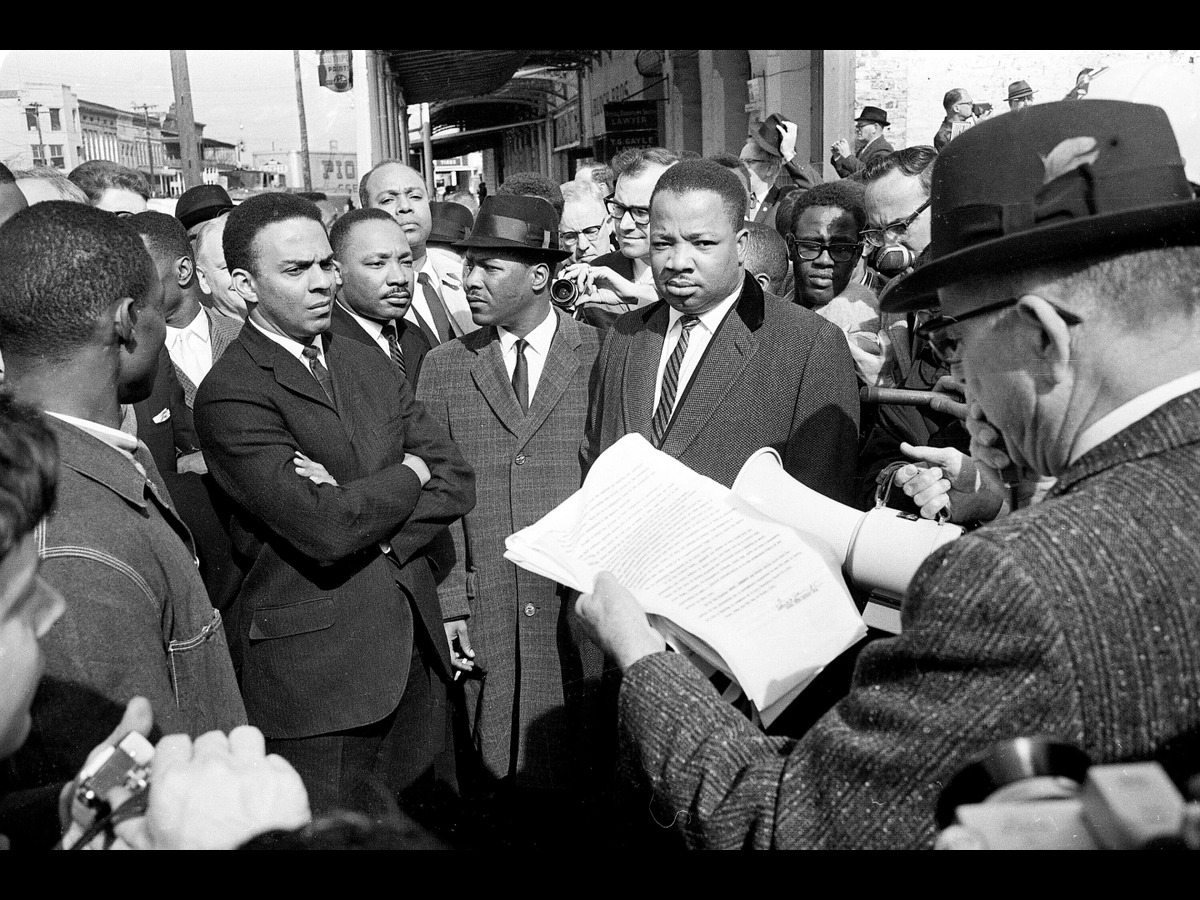

Young felt he should join King’s movement, and in 1957 when he did, his first job was to reply to letters sent to King, who would sign the response.

“He liked the way I answered them and began to ask me to do more,” Young recalled in an interview with The Associated Press. Along the way, he engaged in less glamorous, behind-the-scenes roles.

“With that kind of role, you didn’t get to take part in marches,” he said. “You were always in the back of the bus, the back of the line. But I really wasn’t seeking any recognition. I was trying to do some things that no one else would do. I just kept doing it.”

In 1963 when King was ready to enter Birmingham, Alabama, for his fight against segregation, he asked Young if he knew any white people in the city. “I said, ‘I don’t know any Black people in Birmingham,’” Young recalled. Young had grown up in New Orleans on the same block where the American Nazi party had its headquarters, and King knew that Young would have had some experience with whites as a result.

So, with time, it became Young’s responsibility to hold advance meetings with influential people in communities, including business leaders and the clergy, so they keep abreast with King’s mission, whether they agreed with it or not.

“When it was something that needed to be done, and nobody wanted to do it, that was my job,” Young, now 93, says in a new documentary, “Andrew Young: The Dirty Work” which premiered on MSNBC on Friday and was executive produced by Rachel Maddow.

He goes on to detail what he calls his “dirty work” during the civil rights movement: “Nobody particularly wanted to go meet with white folks. Nobody wanted to take the time to go around and explain to the Black middle class what was going on. In everything I’ve done, in life, there’s always something that somebody considers too difficult and nobody wants to do. That’s what I call ‘the dirty work,’ and I decided that that was my job.”

Through this “dirty work”, Young influenced a major turning point in the fight for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That year, while the U.S. Senate debated the Civil Rights Act, King didn’t want to heighten tensions in St. Augustine, Florida, amid his campaign to end segregation. He didn’t want Young or anyone to get into any conflict with the Ku Klux Klan as he feared that this could thwart the bill’s progress.

But at the end of the day, Young was brutally attacked by the Klan as he tried to de-escalate a potential clash between Klansmen and peaceful protesters. The attack attracted national attention and inspired President Lyndon B. Johnson to sign the landmark legislation.

“I think it was the most successful ass-whuppin’ I had ever received,” Young recalls in the documentary.

In 1968, after King was assassinated, Young thought he could still work behind the scenes to champion the movement’s mission to elect supporters to office. He soon realized that the killings of King and Malcolm X had put fear into people considering running for office.

In the end, Young ran for Congress, winning in 1972 before being appointed as ambassador to the United Nations by President Jimmy Carter.

He also became mayor in the 1980s. A recent program by his alma mater, Howard University, revealed that while serving as mayor, Young “aligned business and political coalitions behind projects that transformed it into a global city: expanding mass transit, recruiting international investment, serving on corporate boards, and championing Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, which has become the world’s busiest airport.”

As co-chair of the 1996 Summer Olympic Games, he would also play a huge role in bringing the centennial Olympic Games to Atlanta that year.