In 2012, writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (pictured below right) provided a thought-provoking TEDxEuston talk that was entitled. “We Should All Be Feminist.” Adichie’s arguments dissect a sensitive issue: the importance of feminism and modern-day criticism of feminism. However, in listening to Adichie’s speech, I was astonished by one statement that has ultimately become the provocation that has led to this article. In her speech, Adichie stated, “An academic, a Nigerian woman, told me that feminism was not our culture. That feminism was un-African. And that I was calling myself a feminist because I have been corrupted by western books.”

I found that statement not only laughable but also profoundly inaccurate.

In response to Adichie’s critic, feminism is indeed our culture and, in fact,  feminism is an important and integral part of Africanism. One cannot call her/himself a true African without embracing the very core of feminism.

feminism is an important and integral part of Africanism. One cannot call her/himself a true African without embracing the very core of feminism.

In order to understand the reasons why feminism is integral to Africanism, one might ask, “What is feminism and who is a feminist?” This is a very important inquiry because it seems the word feminism has become one of the most-misunderstood words in modern language.

SEE ALSO: Kenyan Parliament Amends Polygamy Law: Female Politicians Walk Out

Indeed, the word is now regarded as a curse word. I had always imagined that men may not want to be associated with feminism. The idea that a man is a feminist may cause him to be viewed as a traitor; for, his involvement in feminism means he is “defending the opposite team.” Moreover, why be a man-feminist and appear weak, since a real man should understand the values of masculinity that insists in male dominance and superiority.

However, it seems men are not alone in their feminist-phobia.

Many women also reject any association with feminism. This also initially astounded me. However, having thought about it and discussed it with several women, the reasons for their rejection of feminism are aplenty: they claim a woman who admits to being feminist is aggressive, anti-male, and essentially overbearing. My response is simple: when feminism is bastardized, it is no longer feminism and the true principle of feminism is more profound than the modern-day distorted principle masquerading as feminism.

Merriam-Webster’s dictionary defines feminism as “the theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes.” Personally, I define feminism as the pursuit of fairness and equality.

With either definition of feminism, the idea that feminism is not our [African] culture and that feminism is un-African, is simply preposterous.

I have always considered the true African culture to be the traditions bereft of colonial and imperialistic influence; the traditions created and developed by Africans through their beliefs and core values, communication among themselves, as well as their deities and their land.

However, with the appearance of European and Eastern visitors on African soil, and so-called modernism, these core beliefs and values held devotedly by Africans began to wash away.

Evidently, history seems to suggest that anyone who experiences pre-colonial Africa would learn that deeply rooted in the African culture was what is now known as feminism.

In pre-colonial Africa, many communities were matrilineal and matrilocal. Inheritance of property and most especially, determination of descent, transfer of family names, and prestige were handed down through the female line.

Islamic traveler Abu Abdullah Ibn Battuta, who traveled extensively, visited West Africa in the 14th century. In 1356, he recorded his experiences and revealed that he observed matrilineal communities. He was astonished by this experience because only once had he previously observed a matrilineal society, and that experience was among the non-Muslim Indians of Malabar.

As a consequence of being matrilineal, it is no surprise that many African communities were also matrilocal, meaning men moved in with the families of their wives after marriage. Battuta recalled that he observed men arrive in Masufa and Bardama to marry local women. After the wedding ceremonies, these men remained with their wives in the community. In all his travels, it was the first time Battuta had experienced this practice.

Sociology Professor at Bridgewater College Dr. Mwizenge S. Tembo agrees with Battuta’s observations. According to Tembo, among the tribes located in present day Zambia, marriages were completely matrilocal, “That is to say a man goes to live in his wife’s village,” and said custom was known as ukamwini. However, “after a few years of contact with White civilization and subsequent social change, the custom has gradually changed.”

Both Battuta’s and Tembo’s narratives undermines the notion that in true African tradition, a woman who got married was considered property of her husband. It seems that such accusation is completely inaccurate, and in fact, it was due to the influence of colonialism that African matrilocal culture became extinct.

African Women on the Throne

In addition to matrilineal and matrilocal practices, it was normal for women to ascend the royal throne in pre-colonial Africa. History provides that prior to the 10th century, there is evidence of female rulers in Africa. For example, the Kahina is believed to have been a Queen, religious leader, and military leader of the Djéraoua, a powerful Berber tribe in present-day Algeria.

Makeda, the Queen of Sheba, also reigned over the vast empire that included Ethiopia and set a new standard for women in leadership positions. In 1536, Queen Bakwa Turunku founded the Zazzau Kingdom and created a matrilineal kingdom. Then, in the 1800s, Taytu Betul became the Empress of Ethiopia. She was an astute diplomat and was decisive to the defense of Ethiopia against Italian imperialism. She also founded Addis Ababa, the present-day capital of Ethiopia.

In modern day, the Great Benin Empire located in present-day Nigeria is considered a paternalistic society. However, history reveals that the Benin Kingdom did not previously exclude women from ascending its royal throne until the late-15th century. In 1473 AD, Oba (King) Olua, who was the heir to the throne, initially declined the throne. His sister, Princess Edeloyo was then asked to ascend the throne and she accepted.

As tradition demands, she was conferred with the royal title of “Edaiken” (Heir Apparent to the throne) in preparation of her ascension, but she fell sick. Due to her illness, the uzamas (king makers) superstitiously believed that the gods had rejected female rulers. Thus, they enacted a law permanently prohibiting women from becoming Oba.

One might question the validity of the Bini’s superstition and accuse the Binis of being anti-feminist with their banning of female rulers; however, it is noteworthy that while the Binis’ decision may have negatively affected women, such superstition also benefited women in pre-colonial Africa.

In the Kumbwada Kingdom located in present-day northern Nigeria, one finds a strictly matrilineal monarchy. Men are prohibited from sitting on the Kumbwada throne because they believe a curse was placed on the throne. The curse was discovered more than two centuries ago when a female military general, Princess Magajiya Maimuna, led her cavalry from Zaria and conquered Kumbwada. After the conquest, Maimuna appointed her brother to rule Kumbwada.

Immediately, he fell ill and died within a week.

She then appointed her second brother to rule Kumbwada. Again, the same fate befell him. In discovering that the throne rejected male rulers, she decided to rule Kumbwada and did so for 83 years. In 1958, Prince Amadu Kumbwada stated he wished to succeed his mother and ascend the throne of Kumbwada. Once he uttered those words, he became ill and was rushed out of the kingdom. He never set foot in Kumbwada again.

Accordingly, women have ruled Kumbwada for at least six successive generations, since its conquest by Princess Maimuna of Zaria.

As well as ascending the throne in pre-colonial Africa, it was common for women to hold administrative roles in the community. For instance, the role of Iye-Oba (Queen-mother) in the Benin Kingdom was not ceremonial. The Iye-Oba wielded a lot of political influence in the administration of the kingdom and was considered one of the senior chiefs. Thus, it is no surprise that author Flora Edouwaye Kaplan explains that when the Iye-Oba was depicted, her “sexuality is muted and rendered ambiguous in [Benin] art.”

Pre-colonial African women were also involved in the political process. In fact, a comparison between pre-colonial African women and women of many countries considered pro-feminist reveals an interesting result. For instance, while women in some provinces in the United States voted in 1869; American women officially obtained the right to vote as late as 1920. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, women obtained the right to vote in 1918, but with restrictions. A British woman had no right to vote until she attained the age of 30 (as opposed to age 21 for men) and she must own property or have attained a university education until 1928.

In contrast, while the African political process may have been different, pre-colonial African women had the right to participate in politics.

For example, in the Alaake (King) succession crisis of 1877 in Egba Land (present day Nigeria), Madam Tinubu was the important figure in the selection of the Alaake. She campaigned vigorously for his ascension, contributed financially to his campaign, and garnered supporters (both men and women) for his ascension.

The situation in the United Kingdom is most important to the discussion of women suffrage in Africa because Africa was a British Colony. As a consequence of being a British colony, African women who initially had the right to participate in the political process, officially lost that right.

African Women on the Front Lines

Aside from political involvement, many pre-colonial African women enlisted in the military and defended their communities. During her speech, Adichie stated, “In a literal way, men rule the world, and this made sense a thousand years ago because human beings lived then in a world in which physical strength was the most important attribute for survival.”

I partially disagree with Adichie.

History provides that many pre-colonial African women exhibited physical strength; however, more importantly, intelligence and the ability to strategize was a vital skill necessary for pre-colonial-governance. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Nzinga Mbandi, the Queen of Ndongo and Matamba who defined much of the history of 17th century Angola was a deft diplomat, shrewd negotiator, and formidable tactician.

She led her community to resist Portuguese colonial plans. She spoke Portuguese fluently, which enabled her to communicate with Portuguese kings. She also refused to kneel before the Portuguese — as it was not her custom to do so. She is further renowned for her guerrilla tactics, as her armies were known to attack at night, which caught the enemy unaware.

In 30 years of warfare, she evaded all traps and was never captured.

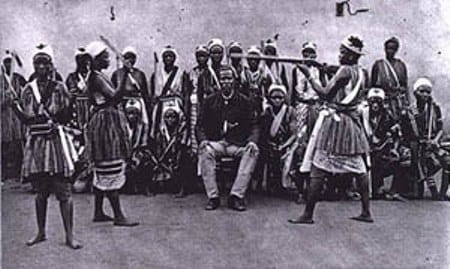

Along with Nzinga, pre-colonial Africa experienced other female military generals  including Yaa Asantewaa (pictured at right) the Edwesohemaa (Queen Mother) of the Edweso tribe in modern day Ghana. She led her army against several oppositions, including the 1900 battle for Independence against the British forces.

including Yaa Asantewaa (pictured at right) the Edwesohemaa (Queen Mother) of the Edweso tribe in modern day Ghana. She led her army against several oppositions, including the 1900 battle for Independence against the British forces.

Also, Queen Idia of Benin defended the Benin army against several incursions, including against the land of Idah. Not only did this defense eliminate the threat of Idah, it also conquered the opposition, which enabled Benin to expand its geographic advantage all the way to the commercially thriving Songhai Empire and then to the Atlantic Ocean.

Additionally, there was Queen Amina of Zazzau. She is considered a legend and known as a great military strategist. She was the head of the Zazzau calvary and fought many battles to the benefit of Zazzau. According to the Sankore Institute of Islamic-African Studies International, Queen Amina “made military assaults upon [several] lands until she proclaimed herself over them by force. The lands of Katsina and Kano were forced to hand over levy to her. She also made incursions in to the lands of Bauchi until she reached the Atlantic Ocean to the south and west.”

The exploits of these female generals culminated in the appearance of one of the most-feared military forces in the history of Africa: the Dahomey Amazon (pictured above). This army was an all-female military regiment that defended the Kingdom of Dahomey in the 18th and 19th century. They were formidable and fearless, especially in close combat and designed the strategy of pre-wartime intimidation. They successfully engaged in many battles, including battles against all-male armies.

The exploits of these female generals culminated in the appearance of one of the most-feared military forces in the history of Africa: the Dahomey Amazon (pictured above). This army was an all-female military regiment that defended the Kingdom of Dahomey in the 18th and 19th century. They were formidable and fearless, especially in close combat and designed the strategy of pre-wartime intimidation. They successfully engaged in many battles, including battles against all-male armies.

In contrast to pre-colonial Africa, several countries that are considered pro-feminist did not permit women to participate in the military. In fact, some of these countries do not permit women to participate in combat today. For instance, It was only in 1949, the United Kingdom officially recognized women as a permanent part of the army. However, full combat roles were restricted to men.

In 1775, 200 hundred years after Queen Amina of Zazzau had led the Zazzau Calvary to combat, the United States only permitted women to serve in the military as nurses, laundry maids, and cooks. It was not until 1948, that the U.S. Congress passed a law officially recognizing women as part of the military. However, as of 2014, American women are still not permitted to partake in military combat. According to a 2013 article written by David Lerman for the Bloomberg News, the United States military informed Congress that “they can open combat positions to women by 2016 without lowering physical or performance standards.”

Nevertheless, it seems natural to assume feminism is un-African but part of the western culture? This is simply not true.

African Women As Entrepreneurs, Landowners

Other than participation in the military, traditional African women also participated in the economic development of their communities: Many women owned farm land, harvested crops, and then traded their crops. For example, among the Kikuyu people in modern-day Kenya, women were the major food producers and distributors. Also, some women chose to engage in the production and trading of hardware.

This was evident in the narration of Battuta who revealed that in the province of Takadda, he observed men and women working together as miners, digging the ore, and taking it to their houses to smelt. Furthermore, women also participated in the business of selling post-produced goods, which brought them great wealth. For example, in the 1800s, Madam Tinubu of Badagry and Princess Aghayubini of Benin were successful traders.

While Tinubu established a flourishing business in tobacco, salt, and gunpowder and maintained a strong trading relationship with European settlers, Princess Aghayubini acquired much wealth through her trade with the Itsekiri people.

The significant wealth acquired by pre-colonial African women provided them with opportunities to purchase property. In Adichie’s speech, she said she knew a woman who sold her home because she felt that owning a home may intimidate men and cost her a potential life partner.

Unfortunately, Adichie’s story is not unusual, as it seems to be a common thought among modern African women. However, this was not the case in pre-colonial Africa. In that period, African women proudly owned properties and land. In some instances, a woman owned multiple properties, which was not considered negative.

For example, in the story of Daura Emirate, the ancient Hausa City that welcomed the founder of Hausa land, Bayajjida, historians report that upon his arrival in Daura Emirates, Bayajjida resided in a house owned by a woman. Similarly, it is documented that among the Kikuyu tribe in modern-day Kenya, women owned a lot of land and possessed the authority to decide how land was used and cultivated in their communities.

Ownership of property was just one demonstration of freedom afforded pre-colonial African women. In her book, “The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century,” writer Rose Dunn explained that when Battuta visited Masufa in present day Mali, he witnessed African women enjoy a kind of freedom he had never previously observed.

According to Dunn, Battuta claimed that Masufa women were “not modest in the presence of men.” Dissimilar to Muslim women in other non-African regions he visited, Masufa women were not required to wear a veil and they dressed as they pleased. They “wear only a waist wrapper which covers them from their waist to the lowest part. But the remainder of their body remained uncovered,” claimed Battuta.

When Battuta was appointed a judge, he decided “to put an end to this practice and commanded the women to wear clothes, but [he] could not get it done,” as the women showed a conviction Battuta had never previously experienced and rebelled against the unprecedented act of control and restriction against their freedom.

Dunn also revealed that on one occasion, Battuta visited the home of a Masufa man and found the man’s wife chatting with another man in the courtyard. Battuta disapproved of this conduct, to which his host responded, “The association of women with men is agreeable to us and a part of good conduct, to which no suspicion attaches. They are not like the women of your country.”

Stunned by his host’s response, Battuta left at once and never returned.

On another occasion, Battuta visited a Judge in the region of Walata. In entering his host’s home, he found a young woman who greeted him. According to Dunn, Battuta was least pleased and narrated, “That a woman should be present in the reception room of a Muslim’s house when a male guest arrived was bad enough, but the Judge’s explanation, that it was all right to come in because the woman was his ‘friend,’ made the visitor recoil in shock.”

Along with the aforementioned freedom, it is reported that women were often the most powerful spiritual figures in ancient Africa and were regularly responsible for the spiritual systems. In many communities, it was believed that only women possessed the spiritual capacity to communicate with the gods. This is fundamentally significant because according to African religion scholar Jacob Olupona, in early African cultures, the “ability to display magical prowess and medicinal knowledge . . . were viewed as signs of bravery and valor when channeled towards the benefit of the community.”

Furthermore, author Jacob Egharevba explains that whereas in modern day culture, economic power is the route to political power, in old African cultures, magical prowess was a well-trodden path to political power and riches. Both Olupona and Egharevba’s comments demonstrate the degree to which pre-colonial African women held power.

In the mid-1800s, Nehanda Charwe Nyakasikana, who was a female spiritualist and considered to be a reincarnation of an oracle spirit in Zimbabwe, rose to become a crucial leader in the First Chimurenga (the war of liberation against British colonial settlers). Similar to Nyakasikana, many pre-colonial African women also enjoyed wealth and political leadership due to their spiritual abilities.

Consequently, it is reasonable to argue that a community that permits women to control an important part of its tradition respects the role of women in its community.

The idea that feminism is un-African has long been repeated as truth; however, it seems that such false idea has arisen out of a re-characterization of the true African story. In fact, during colonization, we also witnessed African women reject unfair treatment. In 1929 and 1947, the British colonial government instituted tax laws in its African colonies that levied more taxes on women than it levied on men.

In response, African women revolted against this unequal treatment and demanded that they be required to pay the same taxes as those levied on men. This is real feminism and this is the real African story.

SEE ALSO: My First Trip to Africa: Hello, Cameroon!

Ewon Adenomon is a graduate student of Journalism at Emerson College, Boston, Massachusetts. To read more from writer, Ewon Adenomon, see Ewontv.com.”