When you ask renowned supermodel Alek Wek (pictured) what it is she loves about Africa, her answer paints a vivid self-portrait of her past journey and sets the stage for where she is yet to go.

Her answer?

“Everything.”

Prodded to go deeper, she adds, “I love everything about it, and I want my friends to come to do things there, spend time there. I wouldn’t be the same person if I wasn’t raised there. It’s the culture, it’s the history, it’s the people. It’s like a home is not a home without the people to make it warm, make it welcoming, and as soon as you land, you can just feel it. I would love one day, coming from a big family, [to be] blessed to have kids to grow up there.”

In between sips of tea, topped with a healthful serving of milk, Alek Wek sits comfortably inside the Crowne Plaza Hotel of Times Square fashionably accentuated with Swarvoski green-tinted crystal earrings and a form-fitting navy blue and hunter green pattern zip dress dress with a smart collar that opens modestly at the breast.

Alek Wek’s story of being discovered at the age of 18 in an outdoor market in London, after fleeing the civil war of Sudan, is a well-prothelytized one. However, even though she has modeled and/or walked for a dizzying array of the top designers and print publications since then — Chanel; Christian Dior; Givenchy; Victoria’s Secret; Moschino; Canadian, Japanese, American, British, and Italian Vogue; Alexander McQueen; Fendi; Armani; Ebony; and more — she talks almost exclusively about her home: Africa.

And indeed, in addition to her childhood, her return to South Sudan in 2012 — barring a brief 2005 visit — left an indelible imprint on her, “Going back for the one year anniversary for the independence was very emotional. I came back and I couldn’t just transition back in to work. There were just so many memories and things that I just wanted to address, like those memories.

“I really needed to put them in to writing. Because it was bigger than Alek Wek. It was the Civil War. The toll it took on the people on even my own family. It really was just so surreal, because [being a refugee] with my family at the time, I never foresaw [independence]. It was like a dream. So it was really important that I went back, because, like they say, you really need to be able to close a chapter on something and then open up another and that’s what I did when I went back. It was very emotional.”

The year was 1985, when civil war broke out in her city of Wau, forcing her family of 11 to flee both rebel and government forces on foot, “I could see my father, and all the miles we walked during the civil war before finally going to seek refuge in London.”

And obviously, much had happened since the time her parents negotiated bodies of water in order to keep their brood of children from drowning. What Wek saw upon her return was a nation that she barely recognized, “There is nothing like home, but to see the level of destruction civil war does overnight…it really is incredible. It takes time to rebuild, but it can just [be destroyed] overnight.

“I also saw the resilience in the people. When I went to the refugee camps, I went to the way stations, I met the internal displaced people (IDP). The new nation, seeing the youth, how vulnerable they were. How much they were in need of education, and that’s something my parents felt really strong about.

“The children, going to schools. Listening to their stories…walking for two hours sometimes three to get to school. Carrying their books, and during the rainy season trooping it, even if they have malaria, really made me sit back and think.”

She also saw the work that UN refugee agency the United Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR) was doing and immediately wanted to get involved.”[After seeing their work in my homeland], I vowed to team up with UNHCR. From Day 1, I was in support of them because I was walking those miles when I was young. Before going to London, I was one of those refugees. I was one of those children.”

And while some may be familiar with Wek the activist, a deeper layer exists explaining her personal devotion to both her homeland and her people: her family.

Wek bubbles with energy as she describes her forward-thinking Father and her deeply rooted and loving Mother.

As a man who worked for the Board of Education, “Mr. Wek,” as Alek refers to him, exercised what most would argue is a radical application of education among his nine children, “For him being a male and saying, ‘I want my girls to have an equal amount of education as my boys. It was really liberating.”

And even though many young girls were being married off, Mr. Wek made sure to tell Alek and her sisters that if they decided to marry, that is a decision they could make several years down the line, “You would never think of a 10-year-old boy marrying a 40-something-year-old women or 50-something, but yet, it was happening to a lot of the young girls. So my father said, ‘It’s not that long you have to wait. Choose and get married if you want to, but first you have to educate yourself, because that’s how you are going to educate your family.

“So I just really applaud him for that, because I don’t know if I would have had that strength in me [to succeed]. And that’s what stuck with me: As soon as I got to London, I felt so happy and blessed. Now I could make something of myself. I can go and further my education. I cannot waste time. I can also crusade and speak on behalf of those who are voiceless.”

And her father’s emphasis on education would indeed drive her thirst for knowledge abroad. And while she would soon be discovered by a model scout agency Models 1 in 1995 and then Ford Models by 1996, Wek already had love for the arts, “I have always enjoyed art. I’ve always made little sculptures out of mud. The Dinka tribe, we love cows. We use them as dowries. We drink a lot of milk! We make cheese. Cows are such a big part of us. So [my interest in art] started at a very early age. But I loved making little cows, and I’d painted them. I’d make some into bulls. My name means a black-and-white cow, Alek. All of [the cows] have different names.”

And her father’s emphasis on education would indeed drive her thirst for knowledge abroad. And while she would soon be discovered by a model scout agency Models 1 in 1995 and then Ford Models by 1996, Wek already had love for the arts, “I have always enjoyed art. I’ve always made little sculptures out of mud. The Dinka tribe, we love cows. We use them as dowries. We drink a lot of milk! We make cheese. Cows are such a big part of us. So [my interest in art] started at a very early age. But I loved making little cows, and I’d painted them. I’d make some into bulls. My name means a black-and-white cow, Alek. All of [the cows] have different names.”

This interest would spur her to enroll in London’s College of Fashion, with a concentration in fashion business and technology.

“When I went to London…and you could go to college and further your diploma and degree. I just couldn’t believe it. When they were like, ‘So, what would you like to major in?’ I just was so happy. I can actually choose what I want to study? It was really profound. So they took us to Oxford, Cambridge — all those universities, and when they took us to the London Institute, I was like, This is where I belong.

“And there were so many other courses you could take. There was business and art or fashion, so that was really my haven. I could just remember Mr. Wek, my dad, saying, ding, ding, ding, ding, ‘If this is what you like, whether it is art, whether it is science, agriculture, you must focus and you must put in the time and energy. You aren’t going to get something out of nothing.'”

Tragically, Mr. Wek would end up hurting his hip during a bicycle accident. And even though he would get his hip fixed, the injury would haunt him later on as a refugee: long hours of walking would infect the hip, causing his untimely death at a relative’s home in Khartoum.

But a light continues to shine in the Wek family, and that bright light is Akoul (pictured seated center), the Mother and absolute matriarch of the Wek family.

Alek’s eyes dance with delight when speaking about her mother, the Mother, who Alek says, “Is wonderful,” and, “Just what a Mom should be.” And while Mrs. Wek was a master teacher of unity and positivity for her children, the lesson that stands the tallest?

Self-love.

“She is the first woman I’d say that inspires me as a woman, makes me want to be the woman I am and will be. She stepped in whenever she saw we were being cross with one another. I think she always said, ‘Cut it out.’ She always helped guide us, helped empower us, and it’s really wonderful, because there is a period of time for a young girl going through — whether it is your early teens or mid-teens — when you’re not sure with yourself.

“Outside plays a role too, because you, [as a female] are not really protected. Now you’re out there, and if you don’t have that concept [of who you are], it can be really challenging, but that’s when I practice all of her wisdom.”

And this self-love would feed and fuel Alek in the world of not just modeling but in the daily navigation of life’s many hurdles and disappointments.

In a recent interview with the Guardian, Wek was asked whether she thought she was beautiful growing up, which seems to be a customary question to ask African women of the diaspora.

Not missing a beat, Wek swiftly responded, “Oh yes, of course.”

Building off of that concrete affirmation, Wek told Face2Face Africa, “No, I felt gorgeous growing up. Absolutely. Maybe at times we all have insecurities, but it wasn’t about whether I felt gorgeous or not. (Shaking her head) No, my mother…it gives me goose bumps still, my mom has raised all five of us girls to know that we are beautiful.

And not just saying it; she has embedded it. And she will be the first one to crusade, if she were sitting right here, she would tell you, ‘You are a woman, own it.’ And I never forgot about that.

“It’s not the hair or makeup that makes you; it’s the woman you are. And we are all different — you’ll see us with my younger sisters; we resemble each other very much, but we all have our own special qualities and my mother always embraced that, and she instilled in us to embrace it. She would always say, ‘You will always have your insecurities, but don’t let your insecurities just take over. Nobody defines you but yourself.'”

In addition to self-esteem, Mrs. Wek also taught her children resilience and dignity.

“Every time there are challenges, I just think about that women with nine children, and this is not the only civil war she’s been through. She’s been through the first civil war, when the peace agreement was in place in the ’60s. She was having some of my siblings, giving birth to them, in refugee camps, whether it was in Liberia or Uganda or Zaire, now it’s Central African Republic, so she’s been through a lot.

“And she kept herself being a woman, being a wife, just humble, so much resilience. So whenever I think things are challenging, I just think about what she had to endure — and still a woman and still a Mother — and I just snap out of it. And I think there’s so many stories like her in Africa and that’s what inspires me a lot.”

“Like I always say, If I wasn’t in London that Sunday afternoon during my second year of college, I wouldn’t have gotten discovered and been able to be a model.

“And in like a year, I almost even quit!

“So thank God I didn’t. I continued my career and I’ve evolved. And there were so many who said I couldn’t have done it. They thought I was weird, I was bizarre, and I said, No, you’re strange, you’re bizarre, because I’m the most normal person.”

The topic of self-esteem, particularly among African girls and women of the diaspora, is a hot-button issue for many. In February, “12 Years a Slave” Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong’o spoke glowingly about how Wek bouyed her self-esteem at a time when her self-image was fragile and she didn’t see any reflections of her beauty in the media.

At the time, Nyong’o famously said:

“And then Alek Wek came on the international scene. A celebrated model, she was dark as night, she was on all of the runways and in every magazine and everyone was talking about how beautiful she was. Even Oprah called her beautiful and that made it a fact. I couldn’t believe that people were embracing a woman who looked so much like me as beautiful.

“My complexion had always been an obstacle to overcome and all of a sudden, Oprah was telling me it wasn’t. It was perplexing and I wanted to reject it because I had begun to enjoy the seduction of inadequacy. But a flower couldn’t help but bloom inside of me. When I saw Alek I inadvertently saw a reflection of myself that I could not deny. Now, I had a spring in my step because I felt more seen, more appreciated by the far away gatekeepers of beauty….”

By April, Nyong’o (pictured at left) would have a public meeting of sorts with Wek (pictured), re-iterating the impact Wek had on her life. Of the meeting, Wek said, “Oh, it was wonderful. I was really caught by surprise when she gave a really touching speech about her personal story,” and I just remember cooking — one of the things I love doing in my private time — [when I heard what she said].

By April, Nyong’o (pictured at left) would have a public meeting of sorts with Wek (pictured), re-iterating the impact Wek had on her life. Of the meeting, Wek said, “Oh, it was wonderful. I was really caught by surprise when she gave a really touching speech about her personal story,” and I just remember cooking — one of the things I love doing in my private time — [when I heard what she said].

“I was really moved, and then I finally got to meet her. She’s a lovely young lady, and I congratulated her for her work. And it was wonderful, because I have been inspired, and we really inspire each other.

“I think real beauty should be celebrated universally, and I think, looking back, coming in to fashion in the mid-’90s, I didn’t understand. Now I understand and I praise my mother even more, because that’s not just Alek Wek. I’d be lying if I said, I’m just Alek Wek, and I did it all by myself.

“Yes, I do have a personality, but what makes me Alek Wek is the woman who came before me. That the woman before me has taken the time to make sure that I feel the way I do. There’s just no way I could have been discovered in a park, started modeling and coming to New York, and made something of myself in the industry.”

For Wek, ultimately, she hopes that other youths can fully enjoy and embrace their natural selves, “I want another young person to never [reject] the color of their skin, not their nose or their culture. It’s a bad thing. If anything, [what you look like] should be a blessing, it should be a benefit. If anything, it should be something to make you proud, and I think we, [as a people], are not there, but we are getting there.”

And for African girls and women who are still struggling to appreciate their God-given beauty, she adds, “You are valid, and if you never heard it, it is never too late. I am an example, and it’s no magic.”

“It is very important to instill self-esteem in our young ones that are vulnerable, because that grows with them. You are beautiful the way you are. You don’t have to conform to anybody, you don’t have to conform to anything, because then, how much are you going to try and compromise and accommodate some type of ideology that makes no real sense. It’s very shallow, and there’s a few things that I don’t have time for: ignorance, stupidity, and pettiness. I keep it moving, like Mother said.

Wek’s message also extends beyond one’s facade. Underscoring the important role education has played in her life, she encourages youth to remember that hard work is the precursor to success, “Once you have the opportunity, you’ve got to work for it. And that’s why I say, Education played a big role in my life. So I think, once the door is open, if one is eager, persistent, and believes in themselves, give them the opportunity, and that’s what I’ve been given.”

Wek’s message also extends beyond one’s facade. Underscoring the important role education has played in her life, she encourages youth to remember that hard work is the precursor to success, “Once you have the opportunity, you’ve got to work for it. And that’s why I say, Education played a big role in my life. So I think, once the door is open, if one is eager, persistent, and believes in themselves, give them the opportunity, and that’s what I’ve been given.”

At this point in time, there is no denying the auspicious positioning of Africa, with the words “Africa is rising,” seemingly reverberating across the continent and the world. Indeed, there is an optimism, viral excitement, and vivaciousness about the continent that has many returning home to contribute, build, and enjoy the incomparable Africa.

Of this, Alek says, “I love it, I love it, and it really touches me. Again, [the youth] could be discouraged, but they just go hard. They are seeing their potential. They see a potential not just in the diaspora, but within them. And I think it’s wonderful. That’s something that’s been willing to burst for so long, and I think all the dots are starting to connect. And I think when they feel that, I feel it, and it’s a wonderful feeling.

“We have to take baby steps, but the fact that we have that energy is wonderful. It’s been about time. For a long time, we’ve been battling. Now is the time with social media. There are some places where we don’t have telephones, we don’t have computers, but we can have access to it and it can reach people from all sorts of places, because people are eager to know what’s going on now and what’s happening. Anything is possible for Africa, and I love to see that.”

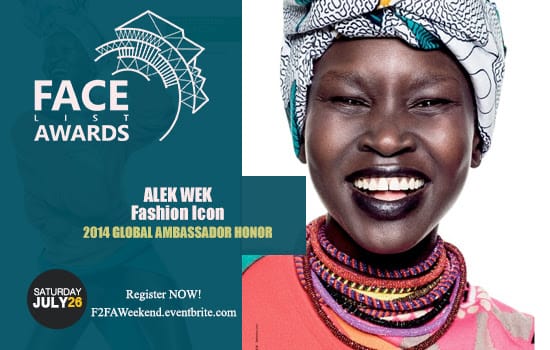

And because one can see how Alek’s strong foundation and identity translates to love of her people, her nation, and her continent, she is Face2Face Africa’s 2014 FACE List Awards Global Ambassador Recipient.

Please join us on July 26th to honor Alek for her commitment to her people and her continent irrespective of where her work takes her throughout the world.