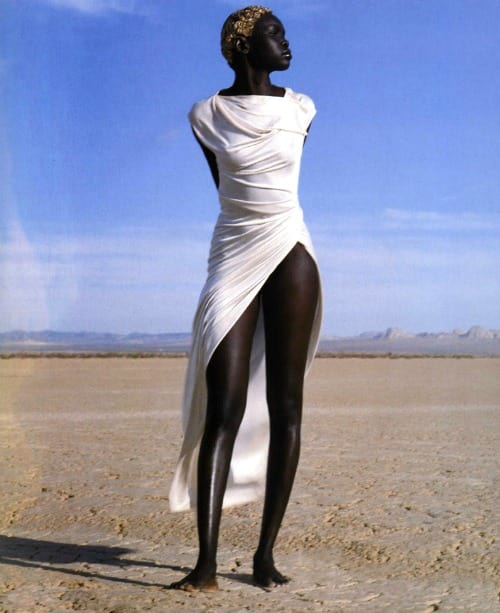

In a recent interview, supermodel Alek Wek (pictured) recounted her journey from refugee to supermodel. Hers is a story that has inspired and continues to inspire many, including “12 Years a Slave” star Lupita Nyong’o.

SEE ALSO: Lupita Nyong’o To Walk Down Aisle with Somalian Rapper K’naan Soon?

Here are excerpts from her interview with the Guardian:

Wek was born in South Sudan, arriving in London when she was 14, and was acutely aware of how different she was from the other big models of the day, women such as Kate Moss, Claudia Schiffer, and Eva Herzigova; while growing up, she had no knowledge of trailblazers such as Iman and Grace Jones.

Keep Up With Face2Face Africa On Facebook!

“There was no concept of fashion and catwalk shows where I came from,” Wek says. “There were no magazines. I never saw women in makeup, or with different hairstyles. Absolutely not.” Now, she says, there are so many South Sudanese girls working as models it is not a big deal; in the late 1990s, she was one of very few successful African models.

“There were Black models, but no one as dark-skinned, and none with Dinka features, that’s for sure.” Even so, she was regularly mistaken for Naomi Campbell, an entirely different-looking model from Streatham with a Jamaican-born mother.

“A black woman is not ‘a type’. I never had any interest in those jobs that asked for only Black girls. What the hell is that? Would you be comfortable saying you wanted only White girls, or Latin? Are you kidding me? It’s baffling.”

At the early age of 19, she was approached by a model scout from a top London agency at a fair in Crystal Palace Park. From the onset, she recalls her mother’s disapproval. Wek‘s mother was thinking that her daughter was going to be a Page 3 girl.

Wek , one of the most successful models of the past decades inherited her father’s height and extraordinarily long limbs, her mother’s high cheek bones, and her “ little booty and big smile” but she is not exactly glamour-girl material. But the agent persisted finally convincing Wek’s mother that their agency was a reputable one and almost immediately Wek’s career took off.

The model went to work in New York and had barely been there when Ralph Lauren booked her to open and close his catwalk show. This was the first time, this had occurred since the spot was normally reserved for a big model and not a newbie. Designers like Calvin Klein, Isaac Mizrahi, Todd Oldham and Anna Sui followed suit. Wek was also booked to star in Tina Turner’s Golden Eye video, named Model of the year by i-D magazine and, in 1997(less than a year after starting out became the first African model to grace the cover of Elle magazine.

At a time when Black models were considered commercially more viable if their hair was relaxed, their complexions light, Wek (very dark skinned, with cropped natural hair) was confident of her value. When asked if she felt beautiful about it, she immediately replies, “Oh yes, of course.”

There’s an argument that this self-belief comes from growing up with what was effectively a media blackout.

“Our confidence came from my mother,” she continues (Alek, pronounced a-LEK, is one of nine children). “She told us it was about celebrating the beauty of being a woman – that’s what made you gorgeous.” Models hear more direct criticism of their appearance than anyone else, with casting agents, editors, and photographers picking apart their features in front of them.

“You can feel very strongly that someone doesn’t like you. I think any model who didn’t have the same sort of upbringing as me would find that very difficult. But I absolutely knew I was entitled. I never thought I was ugly – it never crossed my mind.”

From the start, it was high fashion and couture, not mainstream fashion, that most enthusiastically embraced Wek’s look. “High fashion were the brave ones,” she says. “When I started, I’d hear other people saying, ‘God, she’s so bizarre-looking’, because I didn’t look like the girl next door. But I was just normal. I was the girl next door. There were people in high fashion I could better relate to, who were doing something more interesting and not talking this sort of rubbish.”

Her early life was a peaceful and happy one with her huge family. But at the age of 5, Sudan witnessed a serious civil war which separated the Wek Family. Alek‘s father suffered from stroke and serious infection and her mother started a small salt business to support her family.

Wek arrived in London two years later, to live with her sisters in Hackney (her mother followed when she was 16). She attended the former Hackney Free & Parochial CofE secondary school, though she spoke only Arabic and Dinka; she had never known such cold weather. It was a disorienting time for her.

“It was really, really hard. Children at that age can be such bullies, period. That’s before you even factor in that I looked and sounded so different. But after going through everything, where nothing was ever sure, where I might get killed, I was free and so happy to be learning. I focused on that and threw myself into it.” She was assigned her own special needs teacher and was soon fluent in English.

When asked if she thought modeling itself was also a way of doing something important. The super model said, “Yes, absolutely. But it wasn’t even about Black or White, it was about women. I felt that girls growing up needed to see somebody different, who may have been criticized for their nose, or their hair, or anything – that they could be beautiful. It’s about telling girls from a young age that it’s OK to be quirky, it’s fine to be shy. You don’t have to go with the crowd.”

Read the rest of the interview here.