The ancient Egyptians who were Black Africans by the way and called their land Kmt (land of Blacks) are famed for their science of mummification.

Archeologists, historians and technologists have often wondered the pristine state of many of the pharaohs, their wives and high ranking officials in their tombs or funerary chamber centuries after death if not tampered with by grave robbers.

And now a study is revealing just how the ancient Egyptians perfected the sacred act of mummification – that is embalming a dead body such that it does not go bad to pose a threat to the living.

The new study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Sciences showed certain animals in ancient Egyptian culture were routinely mummified as sacrifices to the gods. It emerged the Egyptian hunters specifically killed them just to sacrifice them — even if they were dangerous beasts like crocodiles.

Aside crocodiles, the ancient Egyptians mummified millions of animals, including horses, birds, cats, dogs, and others. These various animals were associated with different gods and their mummified corpses were used as votives to communicate with the god they represented.

“There are falcon mummies associated with the god Horus, cat mummies for Bastet, dog mummies for Anubis, ibis mummies for Thoth,” Brooklyn Museum Curator Edward Bleiberg explained to the Washington Post.

Crocodiles were associated with the Nile and, by extension, fertility. Sobek, the Egyptian god of fertility took the form of a half-man, half-reptile.

Researchers found the crocodile’s mummification began “very rapidly after the death,” which was caused by blunt force trauma to its head. They came to the conclusion when a 2,000-year-old mummified crocodile which was discovered at Kom Ombo was examined.

To examine the corpse without damaging any bones, soft tissue, and the bandages, the archaeologists used synchrotron scanning. The mummy’s stomach showed it still contained the animal’s last snacks — reptile eggs, insects, a rodent and fish.

“The most probable cause of death is a serious skull fracture on the top of [the] skull that caused a direct trauma to the brain,” the researchers wrote. “The size of the fracture as well as its direction and shape suggest that it was made by a single blow presumably with a… thick wooden club, aimed at the posterior right side of the crocodile, probably when it was resting on the ground.”

Researchers suggest that the hunter, and probably carcasses-for-mummification supplier, likely sneaked up on the beast and whacked it on the head and then took the body away to be turned into a mummy treating its corpse with oil and resins and then wrapping the crocodile in layers of linen.

To determine this, researchers were able to perform a virtual autopsy on the mummified corpse using advanced imaging technology which provided extremely detailed images of each of the mummy’s layers.

They determined that they were dealing with a male juvenile crocodile — likely about three to four years old at the time of its death — with a body length of 3.5 feet.

Thousands of crocodile mummies, some of which were ornately decorated, were found in a crocodile necropolis in the ancient town of Tebtunis in 1899 and 1900, and there is also evidence of crocodile hatcheries and nurseries — both testaments to the crocodile mummy’s popularity and high demand.

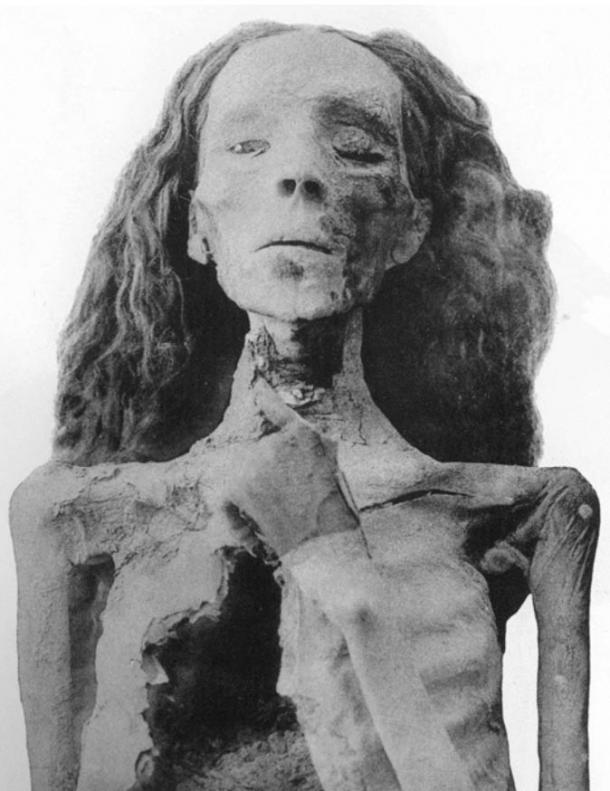

Ahmose-Henuttamehu was found in 1881 entombed in DB320. Like Ahmose-Henutemipet, she was found to be an old woman when she died as her teeth are worn.

Ahmose-Meritamon was found entombed in DB320. Like other mummies of the era, she was found to be heavily damaged by tomb robbers. An examination of her mummy shows that she suffered a head wound prior to her death which was the possible result of falling backwards

Ahmose Inhapy: The mummy was found in the outer coffin of Lady Rai, the nurse of Inhapy’s niece Queen Ahmose-Nefertari. Her skin was still present, and no evidence of salt was found. The body was sprinkled with aromatic powdered wood and wrapped in resin soaked linen.