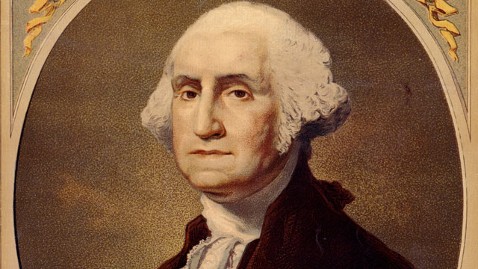

America’s founding father and first president, George Washington, who served from 1789 to 1797 had many victories in the battle field as a military general, as well as, in the political space as a leader and statesman.

While he led Patriot forces to victory in the nation’s War for Independence; one war he didn’t quite win was the war with dental pain.

While dentistry has advanced and a myriad of products and solutions exist today, in Washington’s 18th-century existence, few solutions worked for him.

For years, it was rumoured that Washington’s false teeth were made out of wood. However, the truth is no wood could have survived in a mouth, especially when the liquid and solids would have made it moist and weak leading to decay and untold pain for the bearer.

Starting his military career in the Virginia Militia fighting alongside the British during the French and Indian War, Washington recorded in his diary that he had paid five shillings to a “Doctor Watson” for the extraction of a tooth. During the war, Washington purchased dozens of toothbrushes, tooth powders and pastes, and tinctures of myrrh yet he got little relieve showing as early at that time, his tooth problems had manifest.

In a letter from Washington to his cousin, Lund Washington, who served as the temporary manager of the Mount Vernon estate during the American Revolution, the leader while in Newburgh, New York on Christmas Day, 1782, wrote to Lund asking him to look into a drawer of his desk at Mount Vernon where he had placed two small front teeth.

While it cannot be said for sure who those teeth belonged to, given that Washington owned slaves and Virginia law wouldn’t have penalised him were he to cause the teeth of his slaves to be extracted for his dentures rather than pay heavy sums, it is most likely the source of his dentures.

When Washington died on December 14, 1799, aged 67 years, he owned 317 slaves who lived at Mount Vernon. A simple notation in the Mount Vernon plantation ledger books for 1784 may reveal the source of some of Washington’s denture teeth. The notation simply reads: “By cash pd Negroes for 9 Teeth on Acct of Dr. Lemoin.” Dr. Lemoin being same as Dr. Jean Le Mayeur who corresponded with George Washington about his visit to Mount Vernon that summer.

Wherever Dr. Le Mayeur practiced, he sought out through newspaper ads “Persons who are willing to dispose of their Front Teeth.” While in New York, he advertised that he would pay two guineas each for good front teeth; in Richmond, he stipulated “slaves excepted.” That could explain why the price noted by Lund Washington was so low. Nine teeth sold for two guineas each would be worth almost nineteen pounds; Washington paid only slightly more than six pounds.

It is suggested that when Washington first took the oath of office of the president of the United States on April 30, 1789, he had only one natural tooth remaining.

In the same year, a notable dentist who practiced in New York City called Dr. John Greenwood made a denture for Washington from carved hippopotamus ivory, human teeth and brass nails. Dr. Greenwood made a hole in the denture so the denture would slip snugly over the one remaining tooth – his lower left first premolar – and provide some retention. This tooth would eventually need to be extracted by Dr. Greenwood, who placed this tooth into a locket attached to a pocket watch and chain. Both the locket and the denture now reside in Manhattan’s New York Academy of Medicine.

Even during his second inaugural address in the Senate chamber of Congress Hall in Philadelphia on March 4, 1793, Washington plagued by his dentures rendered the shortest inaugural address in history, lasting only two minutes and consisting of only 135 words.

The curious thing about Washington is that as a slaveholder he also condoned and even encouraged violence as a way to keep enslaved people subservient, buying and selling slaves for economic reasons, sometimes separating families in the process and as president prevented his enslaved servants from learning of their own natural right to freedom, but at the end of his life made the controversial decision against his family’s protestation to free his legal portion of Mount Vernon’s enslaved people.