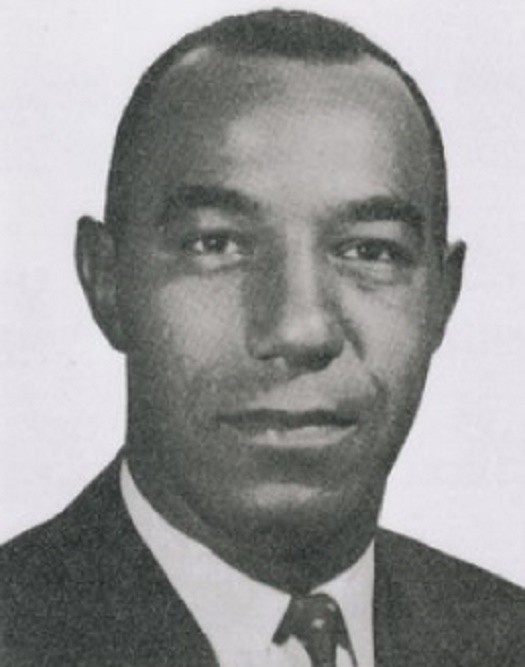

He played down the risk and any racial bias he may have faced at work as America’s first black Secret Service agent. Charles Gittens broke the colour barrier in the service at a time of segregation when black people were not given positions of distinction.

“He would take things with a grain of salt,’’ said Maurice Butler of Washington, who has been researching a biography of Gittens for a number of years.

By 1979 when he retired from the Secret Service, Gittens had served under six different presidents, including John F. Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and Gerald Ford. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was the first president he served under and President Jimmy Carter was the last, an article in The Rider Times said.

He performed his role assiduously, but not without some racial discriminations he faced on the job which he tended to brush aside.

“The racial angle is really hard for him to get at,’’ said his daughter, Sharon Quick, who lives in Washington, D.C. “I never understood it as a child. I don’t know if my father shut his eyes to it,’’ she was quoted by The Boston Globe.

Born in Cambridge to immigrants from Barbados on August 31, 1928, Gittens was the youngest of a family of three brothers and four sisters. After graduating from Morse Grammar School and attending Cambridge High and Latin, he dropped out in 1945 to join the war effort. Then known as Little Charlie, sources say he was determined to join the ranks as his brothers had served in the military and he also “wanted to be with the big guys.”

Before 17, he tried to join the U.S. Army in 1945 but he was turned away. The following year, he enlisted and was stationed with occupation forces in Yokohama, Japan, during the Korean War. Before 19, he had been promoted to the rank of sergeant.

Having heard of the college background and experiences of his fellow soldiers, Gittens decided to take some college courses. He earned his GED while serving in the Army. After his discharge in 1952, he earned a bachelor of arts in three years at North Carolina College (now North Carolina Central University) in 1955 and subsequently taught English and Spanish at Dudley High School in Greensboro, N.C.

He soon developed an interest in law enforcement, particularly, the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, which was then an agency of the U.S. Treasury Department. After a friend had told him that the bureau was hoping to take in black agents, Gittens applied, but was soon recruited by the Secret Service in 1956, which is part of the Treasury Department.

Thus, he became the service’s first African-American agent and was assigned briefly to Charlotte, North Carolina before moving to New York, which was then the agency’s largest office. There, he was part of an elite “special detail” that targeted counterfeiters and other criminals across the country, writes BlackPast.

“There were times he was actually arrested with other criminals,’’ said Butler. Gittens was also held hostage at gunpoint in a New York apartment for a few hours, but he never loved to talk about that, including the other dangers he faced on the job.

Racism, as earlier mentioned, was another obstacle. While guarding President Lyndon B. Johnson on a trip to Dallas, Gittens and other agents entered a restaurant, and its manager refused to serve him because he was black.

Gittens would tell Butler in an interview that he and his white agents had then walked past a “No Negroes’’ sign, which he never imagined applied to him. In Texas at that time, racial segregation was the law, he said.

“‘At that time, I was not a ‘negro,’ I was a Secret Service agent,’’’ Butler read from a transcript of an interview he did with Gittens.

When the manager approached them and said that Gittens could not be served, the black agent told his colleagues not to create a scene and that it was best to leave considering they represented the U.S. president, The Boston Globe report said.

Gittens “didn’t look at anything as a problem,’’ said Butler. “He refused to allow people to bring him down.’’

Gittens had a remarkable career in the Secret Service. He served 23 years in the Secret Service, assigned to New York, as a special agent in charge of the office in Puerto Rico, and then Washington, where he was a special agent in charge in 1971.

By 1977, he was promoted to deputy assistant director of the Office of Inspection, where he was responsible for oversight of all field offices. Two years later, he retired and was hired by the U.S. Department of Justice, where his work in the Office of Special Investigations included the pursuit of former Nazi war criminals living in the United States. He retired from the Justice Department in 1999.

His first marriage to Ruth Hamme ended in divorce after 28 years, while his 10-year subsequent marriage also ended in divorce. Gittens died of heart failure on July 27, 2011, at the Collington retirement community in Mitchellville, Maryland at the age of 82.

At the time of his death, he was not just the first black Secret Service agent, but was also influential in recruiting the first black women into the U.S. Secret Service. He also opened the door for hundreds of minority Secret Service agents who served after him.

“He was a great agent,” said Mark Sullivan, who was then the director of the Secret Service. “When you talk to people who worked with him, the one thing I hear is that he was just a regular guy … a lot of agents, black and white, have benefited from the things he has done. He led by example, and he set the standards for all of us to follow.”

Below is a U.S. Secret Service documentary: