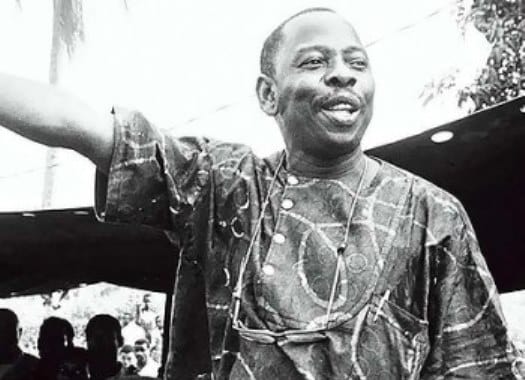

On November 10, 1995, human rights activist and environmentalist Ken Saro-Wiwa (pictured) was hanged for his fearless activism campaigning for his people’s land and rights with his Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP) organization against oil company Shell. On the 20-year anniversary since his murder, Saro-Wiwa’s brother, Owens Wiwa, also a human rights activist, writes a passionate op-ed about his brother’s legacy and the state of Ogoniland today.

SEE ALSO: Wellington Jighere Is First African To Win World Scrabble Championship

Twenty years ago this November, my brother, Ken Saro-Wiwa was executed for his work to rescue our Ogoni homeland in Nigeria from further destruction at the hands of the Royal Dutch Shell plc. Not a day goes by that I don’t miss my brother, but he has especially been on my mind these last six months. I wish he could have seen the growing global movement rising up against Shell’s latest destructive plan: drilling in the ecologically important and fragile Arctic. Activists took to the water in colourful kayaks, hung from a 200ft high bridge, sent letters to President Obama and filled social media with cries of “Shell NO!”

In response, Shell was quoted by the news media as saying, “We have consistently stated that we respect the right of individuals to protest our Arctic operations so long as they do so safely and within the boundaries of law.”

This false benevolence was not in evidence on November 10, 1995, when Shell allowed my brother and eight of his compatriots to be put to death, by the Nigerian maximum dictator, Mr. Abacha, for protesting the company’s operations in Ogoniland.

Wiwa then explains how Shell has impacted Ogoniland:

I know what it is like to live amidst Shell’s oil operations. Ogoniland rests on some 1,000 square kilometers in the Niger Delta region of Southern Nigeria. In 1958, oil was discovered in Ogoniland and, over the next several decades, Shell became comfortable in its occupation, taking our centuries old home as though it were their own. But, where the Ogoni had practiced caretaking and stewardship for this place that fed and provided for us, Shell left a trail of environmental devastation and terrible health impacts on the people still living there.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report on the environmental devastation in Ogoni lays the blame of ecological waste of my community firmly at Shell’s door and reports that it may take 25-30 years to clean up our environment….

The slow poisoning of the land and water began almost immediately. There were constant oil spills and uncontrolled flares. Once thriving fishing areas grew too toxic to support even the smallest creatures and the mangroves — acting as nurseries for marine life in its infancy — which were choked at the roots. Their once bountiful leaves stripped away, leaving behind only skeletons.

Wiwa writes that, at the time of Ken’s activism, he described Shell’s activities as “genocide,” a word that the oil company initially scoffed at but would eventually be echoed by the United Nations.

When my brother insisted that Shell was committing Genocide, the company bristled at the suggestion and took exception to his use of such an emotive word. Well now and independent study funded by Shell has provided compelling evidence and data that goes some way to vindicate my brother’s claims. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report on the environmental devastation in Ogoni lays the blame of ecological waste of my community firmly at Shell’s door and reports that it may take 25-30 years to clean up our environment. To me this sounds like the definition of genocide.

We have lost our land and livelihoods. And I lost my brother Ken. But Shell says it respects the right of individuals to protest.

Wiwa then describes his brother’s genesis into a full-blown defender of both land and people:

It was in 1990 when my brother, a brilliant writer, founded the Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People (MOSOP). It was clear that Shell had no regard for the Ogoni people or the land which had been our home since before recorded history. By this time, Ken had already spent more than 20 years advocating for greater Ogoni autonomy, at one point sacrificing a prestigious position as Regional Commissioner for Education in the Rivers State cabinet for his beliefs.

On January 4, 1993, 300,000 Ogoni celebrated the Year of Indigenous Peoples by protesting against Shell. My brother addressed the crowd saying, “We have woken up to find our lands devastated by agents of death called oil companies. Our atmosphere has been totally polluted, our lands degraded, our waters contaminated, our trees poisoned, so much so that our flora and fauna have virtually disappeared.”

With MOSOP, Ken spoke and wrote about our plight. He educated and organised. He opened eyes to the great cost being paid in the pursuit of the great rewards Shell promised, and raised voices in solidarity and hope.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t long before the powers that be took notice of Ken’s activities:

The show of strength in the face of their oppression worried Shell’s leadership and, in a partnership as horrifying as it is unbelievable, the company began conspiring with the Nigerian military. Soldiers — operating with financial support from Shell — brutalised the Ogoni people, then took my brother into custody, tortured him and ultimately put him to death. All for trying to prevent Shell from leaving Ogoniland an empty, poisoned husk.

And 20 years after Ken’s execution, Ogoniland is still suffering from Shell’s presence:

A study by the United Nations Environment Programme has shown that, despite the fact that no oil production has taken place in Ogoniland since 1993, oil spills continue to occur with fierce regularity. The production facilities that Shell used to crowd out farmers and fishermen have fallen to rust and ruin, and neglected, antiquated pipelines continue to leak oil as they snake from other parts of Nigeria through Ogoniland. Fishermen and farmers can no longer make their living or feed their families from the water or the field.

This is the bounty that Shell has brought to the Indigenous people of Ogoniland. It promised prosperity and a bright tomorrow. When it wants to distract people from the price that will eventually be paid, Shell talks of jobs, crows about its lavish philanthropy and promises that no harm will be done, no chaos left in its wake.

And with the fight to reclaim what is theirs still continuing, Ken’s last words were prophetic:

When my brother Ken was executed, his last words were “Lord, take my soul… but the struggle continues.” I hope Ken is watching and seeing that, yes, it does. From Ogoniland to the Arctic and beyond, people are rising up to say “Shell No!” They are standing strong against a corporation and an entire industry that will mortgage our future for quick profits. I can’t think of a better way to honour my brother.

SEE ALSO: Nigerian Artisan Creates Raffia Car To Show Black Talent to World