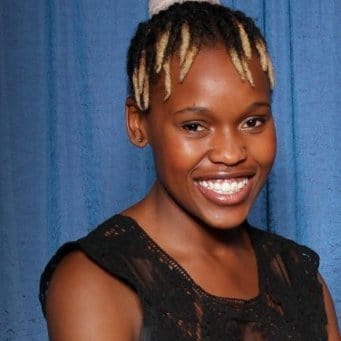

Last month, the University of Cape Town voted to remove the statue of British colonizer Cecil Rhodes, after it was targeted by a student who smeared it with excrement. The defacement prompted a powerful discussion about the necessity and relevance of having colonialists’ statues around South Africa. Last Saturday, the statue was finally removed, and performance artist Sethembile Msezane was there dressed as the Zimbabwe bird statue (pictured) that was taken by Rhodes from Great Zimbabwe. In a recent interview, Msezane shares her experience taking part in the removal with her art and explains the general sentiment about Rhodes’ statue — and other statues of that era — below.

RELATED: UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN TO REMOVE STATUE OF BRITISH COLONIZER CECIL RHODES

Msezane says that even though people would like to believe that anyone “Born Free,” or  born after Apartheid, has nothing to complain about, that belief is simply untrue.

born after Apartheid, has nothing to complain about, that belief is simply untrue.

I was born in the ’90s, but I’m not a Born Free; it was before South Africa became a democracy. Many believe that my generation doesn’t have anything to protest against. Given that police threw stun grenades at a student protest outside parliament last month, that is far from the truth.

On why Msezane decided to start doing performance art, she explains that she began because she noticed a dearth of “Black female bodies” in public spaces.

I believe that South Africa’s memorialised public spaces are barren of the black female body, so last year I started doing performance art (I’m a fine arts student at the University of Cape Town) to draw attention to the issue. I performed as Lady Liberty on Freedom Day, Rosie the Riveter on Women’s Day. The character I’m portraying here depicts the statue of the Zimbabwe bird that was wrongfully appropriated from Great Zimbabwe by the British colonialist Cecil Rhodes. It currently sits in his Groote Schuur estate.

Msezane says she knew that Rhodes’ statue had to eventually be taken down, so she began preparing her outfit for the event.

Standing in “high heels” Msezane says she looked in to attendees sunglasses in order to determine when was the right time to raise her wings.

I looked at people’s phones and sunglasses, trying to see the reflection of the statue coming down. I saw the shadow move and thought, “This is the moment.” That’s when I lifted my wings.

I was up there for four hours. I would hold up my wings for about two minutes, take a 10-minute break and then put them up again. My legs hurt, but I didn’t realise how sore my arms were until I came down – they were shaking.

My feet were blue, I was sunburnt; I had heat stroke and blurry vision from looking directly into the sun. I went home, had a shower and went straight to sleep. I felt like we were beginning to question this idealistic “rainbow nation.”

For South Africans, Msezane explains that the removal of the statue is a watershed moment for the people, because the targeting of Rhodes’ statue began an important discussion about whether these statues were even needed at all.

I’m not sure that we need statues at all – it’s a colonialist thing, like marking territory. My work is a response, to get people to look at the landscape with a different eye. People haven’t forgiven or forgotten, they’re still harbouring hatred. That’s why the statue needed to fall. It fostered the kind of thinking that is dangerous to a country in healing.

RELATED: WITH SOUTH AFRICA’S COLONIALISTS TARGETED, SARAH BAARTMAN’S GRAVE IS DEFACED