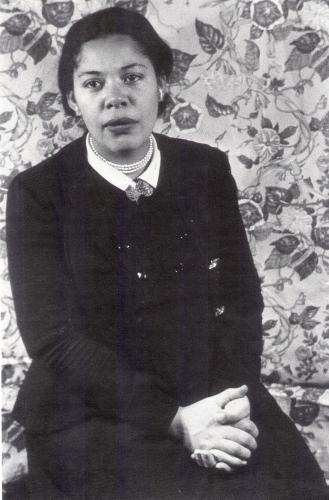

Her 1946 novel The Street was one of the first to address the experiences of black women in terms of race, gender and class.

Ann Petry’s ground-breaking novel, which was highly praised around the world, would also become the first book by an African-American woman to sell over a million copies.

The Street presented a powerful portrait of the daily life of residents of Harlem in the 1940s, particularly, the effects of bitter racism and sexism on an African-American mother as she tries to offer a better life for herself and her son.

“In ‘The Street’ my aim is to show how simply and easily the environment can change the course of a person’s life,” Petry once said.

A review of her works by Parul Sehgal in The New York Times said it was impossible not to connect Petry’s own childhood to her fiction.

Born and raised in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, where she lived most of her life, Petry’s father was a pharmacist and her mother ran a business called Beautiful Linens for Beautiful Homes. Petry would become a trained pharmacist after graduating from the Connecticut College of Pharmacy. She worked in the family’s drugstores in Old Saybrook.

But as Seghal writes, her family was one of four black households in Connecticut and were usually harassed.

“She was ordered to leave a public beach as a child, and pelted with stones as she walked to school, where white teachers refused to instruct her. These experiences of feeling scrutinized, even hunted — and her observations of Harlem from her time writing for Adam Clayton Powell’s newspaper The People’s Voice — course through her fiction,” Sehgal noted.

As a trained pharmacist, Petry’s life took a different turn in 1938 when she married George Petry, a Louisiana-born resident of Harlem and they moved to New York City.

Soon, her interest in writing began. She started off with short stories and worked for the Harlem Amsterdam News before covering general news stories and editing the women’s pages of the People’s Voice in Harlem by 1941. In 1943, her first published story, On Saturday the Siren Sounds at Noon, appeared in the Crisis, a magazine published monthly by the NAACP.

Within three years, she had begun work on her first novel, The Street, which would make her the first African-American woman writer to attain bestseller status, having sold over a million copies. She also earned several literary awards, including the Houghton Mifflin Literary Fellowship.

“The book’s empathetic depictions of broken lives on a single stretch of a Harlem street were both a critical and commercial success. Critics hailed the novel as skillfully written and powerful, while the public made it a bestseller,” a profile of Petry on Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame said.

Soon, Petry gained wide public attention which she was not ready for so she moved from Harlem and returned to her hometown, Old Saybrook.

“My soul was no longer my own,” she recalled to The Times in 1992.

“I was a black woman at a point in time when being a writer was not usual, and I was besieged. Everyone wanted a part of me.”

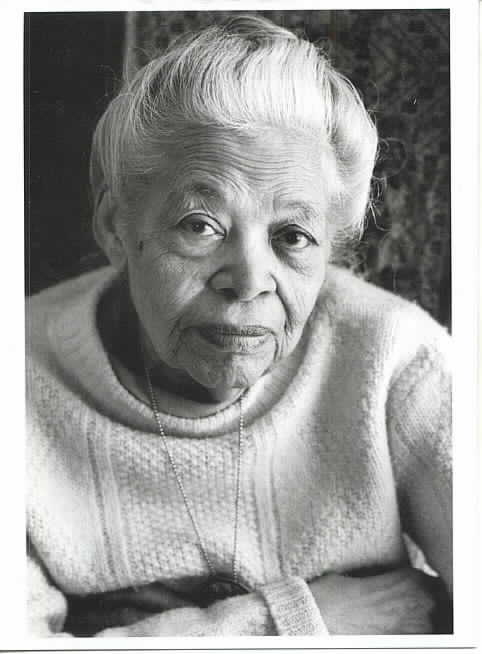

Even in Old Saybrook, Connecticut, she was still against any sort of exposure to the extent that she destroyed some of her pieces of writing. Nevertheless, the Connecticut writer and novelist would go ahead to publish seven more books, including two additional novels, The Country Place and The Narrows. She also published numerous short stories, articles and children’s books in the 1950s and 1960s.

She once said that her historical books for juveniles have several messages for young readers, including the simple reminder that black people have formed an integral part of American history: “Over and over again I have said: These [characters] are people. Look at them, listen to them; watch Harriet Tubman in the nineteenth century, a heroic woman, a rescuer of other slaves. Look at Tituba in the seventeenth century, a slave involved in the witchcraft trials in Salem Village. Look at them and remember them.

“Remember for what a long, long time black people have been in this country, have been a part of America: a sturdy, indestructible, wonderful part of America, woven into its heart and into its soul.”

“These women were slaves. I hoped that I had made them come alive, turned them into real people. I tried to make history speak across the centuries in the voices of people–young, old, good, evil, beautiful, ugly.”

Petry was appointed visiting professor of English at the University of Hawaii (1944-1945) and lectured widely throughout the United States. In the 1980s, she received honorary degrees from Suffolk University, the University of Connecticut, and Mount Holyoke College. She passed away in her hometown, Old Saybrook in 1997.

Her first two novels, although set in Harlem, are usually considered part of the Chicago (Illinois) Black Renaissance in literature, and are often compared with the works of the prominent Chicago writer and social critic Richard Wright.

“Both authors held a deterministic outlook for urban America, seeing black urban life as a site of hopelessness that generated only slums and limitations, especially after the Great Migration,” writes Blackthen.