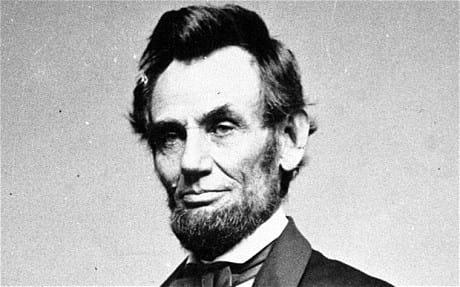

Jomo Kenyatta (pictured) led Kenya from its independence in 1963, ushering in new change for the nation after years of British rule. While still in office, Kenyatta died on this day in 1978, leaving behind a legacy that has been both praised and criticized.

SEE ALSO: EFF Heckles Zuma As He Responds To Money Mismanagement Allegations

Kenyatta was born Kamau wa Ngengi on an unknown date in the 1890s. Early birth records of  Kenyans were not kept so there is no way to determine the official day. Kenyatta was raised in the village of Gatundu by his parents as part of the Kikuyu people. After his father died, he was adopted by an uncle and later lived with his grandfather who was a local medicine man.

Kenyans were not kept so there is no way to determine the official day. Kenyatta was raised in the village of Gatundu by his parents as part of the Kikuyu people. After his father died, he was adopted by an uncle and later lived with his grandfather who was a local medicine man.

Entering a Christian missionary school as a boy, Kenyatta worked small chores and odd jobs to pay for his studies. He then converted to the Christian faith and found work as a carpenter. Kenyatta married his first wife, Grace Wahu, in 1920 under Kikuyu customs but was ordered to have their union solidified by a European magistrate.

Kenyatta’s political ambitions grew when he joined the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), becoming the group’s general secretary in 1928. Working on behalf of the KCA, Kenyatta traveled to London to lobby over the right to tribal lands.

Kenyatta did not get support from the British regarding the claims, but he remained in London and attended college there. While at University College London, Kenyatta studied social anthropology.

Kenyatta came to embrace Pan-Africanism during his time with the International African Service Bureau, which was headed by former international Communist leader George Padmore. Kenyatta’s thesis from the London School of Economics was turned into a book, “Facing Mount Kenya,” and he went on to become one of the leading Black-emancipation intellectuals alongside Padmore, Ralph Bunche, C.L.R. James, Paul Robeson, Amy Ashwood Garvey, among others.

The Mau Mau Rebellion of 1951 was a time of political turmoil in Kenya, still known as British East Africa. The Mau Mau were in open opposition of British colonizers, and Kenyatta was linked to the group. Despite little evidence connecting Kenyatta to the “Kapenguria Six” – the individuals accused of leading the Mau Maus, Kenyatta spent nine years in prison.

He was released in August 1961, which set the stage for bringing about Kenya’s independence.

Kenyatta joined the Legislative Council, and he lead the Kenya African National Union (KANU) against the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) in a May 1963 election. KANU ran on a unitary state ticket, while KAU wanted Kenya to run as an ethnic-federal state.

Kenyatta joined the Legislative Council, and he lead the Kenya African National Union (KANU) against the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) in a May 1963 election. KANU ran on a unitary state ticket, while KAU wanted Kenya to run as an ethnic-federal state.

KANU defeated KADU handily, and in June 1963, Kenyatta became the prime minister of the Kenyan government. Although the transfer of power was slow to come, with Queen Elizabeth II remaining as “Queen Of Kenya,” Kenyatta eventually became the nation’s first president under independence.

Kenyatta’s health had been poor since 1966, when he suffered a heart attack. He ruled, however, as a leader open to reconciliation with the British and Asian settlers in the land. Kenyatta embraced a capitalist model of the government, although some experts write that he selfishly promoted those from his own circle and tribal line to positions of power. Still, Kenyatta was beloved by many all the same, despite the rumblings that in his later years he had no control over government affairs due to his failing health.

Kenyatta died of natural causes, later succeeded by his Vice President Daniel Moi. Today, the late-first president’s son, Uhuru Kenyatta, is the current and fourth president of Kenya.

SEE ALSO: Soldiers Mutiny Over Inferior Arms Given in Face of Boko Haram?