David Drake was known for his large-sized historic pots that could hold 40 gallons of water. His large clay pots were also used for food storage in the 1850s. However, since he was an enslaved man in South Carolina, he wasn’t allowed to own any of his work.

After almost 200 years, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts has made this happen by granting ownership of two of David Drake’s stoneware vessels to his descendants.

“Our great-great-great-grandfather never got to own one single piece of his own pottery or to pass them on to his children and grandchildren,” Pauline Baker, one of David Drake’s descendants, said in a statement cited by WBUR. “Today the museum does all it can to right that wrong.”

After the official return of the vessels, the museum repurchased one of the pieces, the Poem Jar, from David Drake’s family. The family then went on to give the other pot, known as the Signed Jar, to the Museum of Fine Arts under a long-term loan agreement.

Many museums in recent times have been called upon to repatriate stolen artworks and artifacts. Some institutions start the process on their own to return the artifacts, as was the case with the Museum of Fine Arts. Three years ago, the museum partnered with New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art on “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” an exhibition that commemorated David Drake and where he came from. While working towards the show, the museum worked with David Drake’s descendants, which eventually resulted in discussions about repatriation, according to the New York Times.

“There’s literally no precedent for this,” George Fatheree, a lawyer for Drake’s descendants, told the Boston Globe. “Works by enslaved African American artists have been absent from the art world’s conversation about restitution, but the museum’s action really changes that forever.”

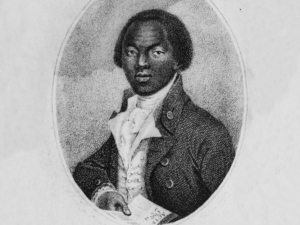

David Drake, also known as “Dave the Potter”, was born sometime in 1801 on a plantation in either North or South Carolina and supervised by Harvey Drake, according to the Oak Spring Garden Foundation.

David Drake learned the ropes of the trade from Harvey Drake and Abner Landrum, who ran a pottery business in what has become known as Edgefield in South Carolina. David Dave had learned to read and write, possibly from Landrum, even before it became legal for enslaved persons to acquire literacy in 1740.

When Harvey Drake passed away in 1833, David Drake had no choice but to serve different owners, from Landrum’s son, Rev. John Landrum, to his son, Frank Landrum, and finally with Lewis Miles in 1849. David Drake’s significant work of pottery, according to historical accounts, was during his stay with Miles from 1864.

When David Drake attained his freedom after the Union victory in the Civil War in 1865, he added the last name of Drake to his identity. He is presumed to have died somewhere around the 1870s because his name was not captured in the U.S. census of 1865.

David Drake’s pottery was acclaimed because of the combination of quality invested in it to produce alkaline glaze which made it suitable to store water and food. His large-sized ceramic pots with the capacity to hold 40 gallons of water stood over two feet tall. Historians argue that David Drake must be a man of sheer size and height to produce such an exemplary work of art to hold such volumes of water.

Oral history posits that he lost one of his legs in a train accident but it did not become a liability. It gave him an added advantage over his pottery wheel to craft one of the most impressive ceramic pots at the time. Historians say that he threw thousands of wares during his lifetime, and his wares were mostly sold to plantations where they were used for food storage.

He is noted to be the first African American to sign his ceramic pots with his name and other inscriptions. This was seen to be an act of defiance because it was illegal for enslaved men and women to read or write at the time. On one of his pieces, David Drake looked back at his separation from his family, who were also enslaved.

“I wonder where is all my relation / Friendship to all—and every nation,” he wrote, according to Boston Globe.