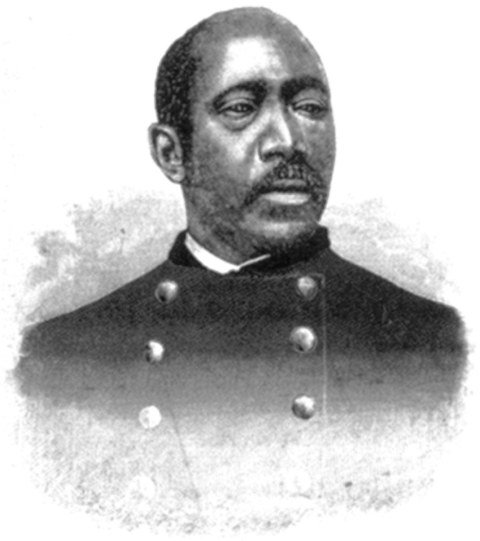

Martin Robison Delany advocated for black emigration at a time when many other abolitionists were championing the need for freed blacks to go ahead with the anti-slavery battle in America.

Historians say the message of Delany, an African-American civil rights activist, author, editor, and doctor, did not go down well with the people, including both white and black Americans.

Thus, he is largely not popular compared to his colleagues like Frederick Douglass, whom he would work with, though the two would have different perspectives on what black freedom entailed.

In spite of this, Delany is remembered today as the father of black nationalism whose role in the anti-slavery movement before and after the Civil War cannot be underestimated.

Born to a slave father and a freed mother on May 6, 1812, in Charles Town, W.Va. (which was then Virginia), Delany’s mother, Pati, had difficulties teaching him and his siblings to read and write as state laws at the time prohibited education for black children.

Pati had to move the children to Pennsylvania in 1822 to avoid their persecution; this enabled Delany to study without any interference. When he was 19, Delany walked all the way to Pittsburgh, where he became a student at a school operated by the Rev. Lewis Woodson of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Woodson is remembered as a strong advocate of black economic freedom and for his role in the Underground Railroad which helped slaves escape to freedom in Canada.

Delany would also play an active role in the activities of the Underground Railroad and would subsequently introduce an abolitionist newspaper, The Mystery.

He was also trained in medicine and by 1837, he had opened a successful medical practice in cupping and leeching. After almost ten years, in 1846, the famous abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, arrived in Pittsburgh from Rochester, New York, to seek the services of Delany as co-editor of his new newspaper, The North Star.

For the next 18 months, the two worked together in producing and promoting the newspaper, which allowed African Americans to tell their own stories.

The two never worked in an office together, though. While Douglass stayed in Rochester handling the editing and printing of the publication, Delany travelled on western tours to Ohio and Michigan to spread the messages of the newspaper and recruit subscribers, according to Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

In the 1850s, Delany published The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, Politically Considered, in which he claimed that blacks would never be considered equals, even by abolitionists, hence they must emigrate to Africa.

Though he and Douglass would remain friends after their work together, the latter’s view on black emigration did not resonate well with Douglass, causing the two to eventually go their separate ways.

Historians believe that Delany’s hatred towards America may have been caused by an unfortunate experience in 1850. Delany had entered Harvard Medical School that year to finish his formal medical education, alongside two other black students. The three were, however, dismissed within a few weeks after petitions to the school from white students.

That same year, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slave owners to pursue and capture escaped slaves while establishing fines for any law enforcement officer who refused to make such arrests.

For the next decade and a half, Delany continued to fight strongly for emigration, first to Central or South America, and then to Africa. In 1859, he led an emigration commission to West Africa to explore possible sites for a new black nation along the Niger River, said BlackPast.

Delany would move to Canada, where he would stay until after the Civil War began in 1861. Having returned to the U.S. during the war, Delany recruited blacks to join the Union Army.

In 1865, he persuaded the administration of President Abraham Lincoln to create an all-black Corps led by African American officers. Delany got commissioned as a Major in the 52nd U.S. Colored Troops Regiment, making him the first line officer in U.S. Army history.

After the Civil War, Delany went to South Carolina, where he worked with the Freedman’s Bureau during Reconstruction. There, he did not only call for land for African Americans but also demanded the enforcement of black civil rights and black pride.

The author and abolitionist later became active in the Republican Party but lost his chance at becoming Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina. He subsequently served as a Charleston, South Carolina judge.

In 1879, he published The Principia of Ethnology, a book which discussed racial pride and purity. He went ahead to urge African Americans to emigrate to Africa until his death in Xenia, Ohio on January 12, 1885.

Till date, his name, according to most historians, has not ‘persisted in public view’ largely because he did not self-market himself like others, including Douglass.

Nevertheless, historian John Stauffer from Harvard University believes that “Delany is second only to Frederick Douglass in significance and impact as a black leader.”