In the 1940s when anti-apartheid leader and activist Nelson Mandela joined the African National Congress (ANC), it was an organisation protesting the South African government’s policy of apartheid.

The country then had an all-white government which developed a racial segregation system called apartheid, under which nonwhites (the majority of South Africa’s population) were treated as second-class citizens.

Contact between white and nonwhite communities during this period was limited as blacks were forced to live away from the whites and to use separate public facilities. Despite strong resistance against apartheid, these discriminatory laws remained in effect for at least five decades.

A member of the ANC, Mandela became a leader of both peaceful protests and armed resistance against the white minority rule. By 1949, a year after apartheid fully began, the ANC adopted the ANCYL’s plan to achieve full citizenship for all South Africans through boycotts, strikes, civil disobedience and other nonviolent methods, according to History.

Mandela would travel across the country to organise protests against discriminatory policies and would play influential roles in the setting up of South Africa’s first black law firm in 1952, which offered free or affordable legal counsel to people affected by apartheid legislation.

On December 5, 1956, Mandela and some 155 other activists were arrested and went on trial for treason, but they were all acquitted in 1961. During that period, tensions were brewing in the ANC, as a militant faction left the organization in 1959 to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC).

The PAC would lead peaceful black protestors in the township of Sharpeville to protest the Pass Laws, a passport system enacted under Apartheid to further segregate the population.

Police opened fire on them, killing 69 people and injuring 180 in what became known as the Sharpeville massacre. The anger and riots that accompanied this compelled the apartheid government to ban both the ANC and the PAC.

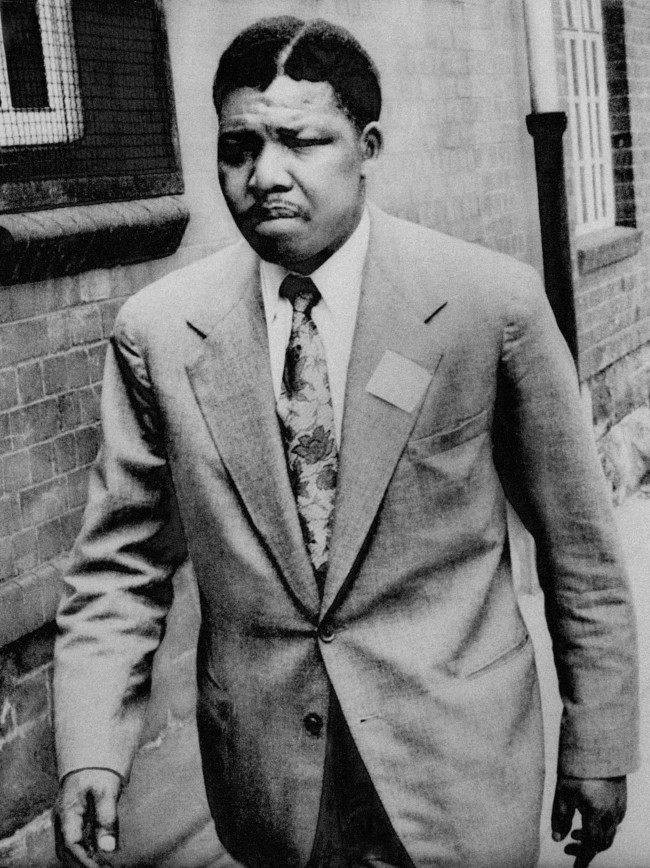

Figures like Mandela were, therefore, forced to go underground and adopt a number of disguises; sometimes a labourer or a chauffeur just to evade the police. By 1961, Mandela realized that non-violent measures would not be successful in getting their demands met, hence, he and other ANC leaders formed Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), a militant wing of the ANC.

“Under Mandela’s leadership, MK launched a sabotage campaign against the government, which had recently declared South Africa a republic and withdrawn from the British Commonwealth,” writes History.com.

Other accounts state that the group launched bombing attacks on government targets and made plans for guerilla warfare. What perhaps angered authorities was when Mandela travelled to the United Kingdom and to other African countries without an official passport.

In January 1962, the anti-apartheid leader travelled abroad illegally to attend a conference of African nationalist leaders in Ethiopia. His trip was also to visit the exiled anti-apartheid politician Oliver Tambo in London and undergo guerilla training in Algeria.

Shortly after Mandela’s return to South Africa on August 5, he was arrested and consequently sentenced to five years in prison for leaving the country illegally and inciting a 1961 workers’ strike.

That wasn’t all for Mandela as the following year, in July, the police raided Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia, Johannesburg, which was said to be an ANC hideout and arrested some MK leaders. The police also took along supposed evidence of plans by Mandela and others to sabotage and lead a violent revolution against the apartheid government.

Mandela and seven of his comrades were brought to stand trial for sabotage, treason and violent conspiracy in what became known as the Rivonia Trial.

Though the Rivonia Trial, which took place between October 9, 1963, and June 12, 1964, was strongly condemned by recognized international organizations, including the United Nations and the World Peace Council, it still proceeded and eventually found Mandela together with the other accused guilty.

Mandela was sentenced to life imprisonment alongside the seven others. The prosecution pushed for a death sentence but the presiding judge opted for life imprisonment.

During the trial, Mandela decided to give a statement from the dock instead of taking the witness stand. In a lengthy statement from the dock on April 20, 1964, he admitted to many of the charges against him but defended the motives of the ANC and MK and his use of violence.

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die,” he concluded.

Mandela served 27 years in prison, initially on Robben Island, and later in Pollsmoor Prison and Victor Verster Prison.

He was released in 1990 following the relaxation of apartheid laws, including the unbanning of liberation organisations like the PAC and the ANC by the then South African President FW de Klerk.

After leaving prison, Mandela worked hard to ensure that human rights were respected and South Africans had a better future. He would eventually become the first black president of South Africa in 1994.