P.W. Botha, state president of South Africa from 1984 to 1989, was a staunch supporter of policies that kept Black people in the nation from gaining majority rule. With his racist Apartheid policy drawing the ire of world leaders, Botha boldly threatened to exile more than 1 million foreign Blacks from the country on this day in 1985.

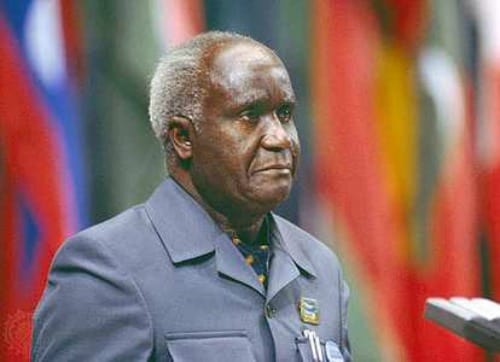

SEE ALSO: Zambian President Accuses Briton, U.S. of ‘Kissing Apartheid’ on This Day in 1986

On July 21, 1985, South Africa was under a government-endorsed state of emergency. The United Democratic Front (UDF), one of the most-active anti-Apartheid groups in the country, were especially targeted under the martial law of Botha’s forces, causing France to impose sanctions against the country in light of the violent attacks on the UDF and Blacks in the country.

Bishop Desmond Tutu requested to meet with Botha to discuss a possible resolution and end to the state of emergency, which the President rejected.

The tensions in the country mounted as sanctions from the United States and other countries loomed and could have potentially hurt South Africa economically.

Botha threatened that if France and other nations continued to impose sanctions, he was going to expel 1.5 million of the nation’s foreign Blacks who were in the nation for work. Around 500,000 of these individuals worked in South African mines while others held other menial jobs across the country.

The Los Angeles Times reported on Botha’s statement then:q

President Pieter W. Botha threatened today to expel as many as 1.5 million foreign Blacks working in South Africa if other nations join France in imposing sanctions to protest the 9-day-old state of emergency.

Botha’s comments came a few hours after he rejected talks with Bishop Desmond Tutu about the state of emergency declared July 21 in an attempt to end 11 months of racial violence in the country’s Black townships.

Speaking at a youth rally in Potchefstroom, about 75 miles west of Johannesburg, Botha gave his toughest rejection yet of Western criticism, warning that any sanctions would spark retaliation by South Africa.

Even though he said that he and supporters did not “want crumbs from the master’s table,” Tutu was one of the few Black leaders willing to hold an audience with Botha. Therefore, Botha’s refusal to meet understandably angered Tutu.

Botha suffered a stroke in 1989 and was forced to step down from his post.