Rosa Ingram, a widowed mother of 12 children, was working on land she sharecropped near the small town of Ellaville, Georgia, on November 4, 1947, when John Stratford, a white neighbor, confronted her over her livestock crossing over onto his property.

Various accounts state that the white landowner was armed with a knife and rifle when he approached Ingram.

Author Janus Adams wrote in the book Sister Days: 365 Inspired Moments in African-American Women’s History that Stratford, in the course of the argument, struck Ingram in the face with the butt of his rifle.

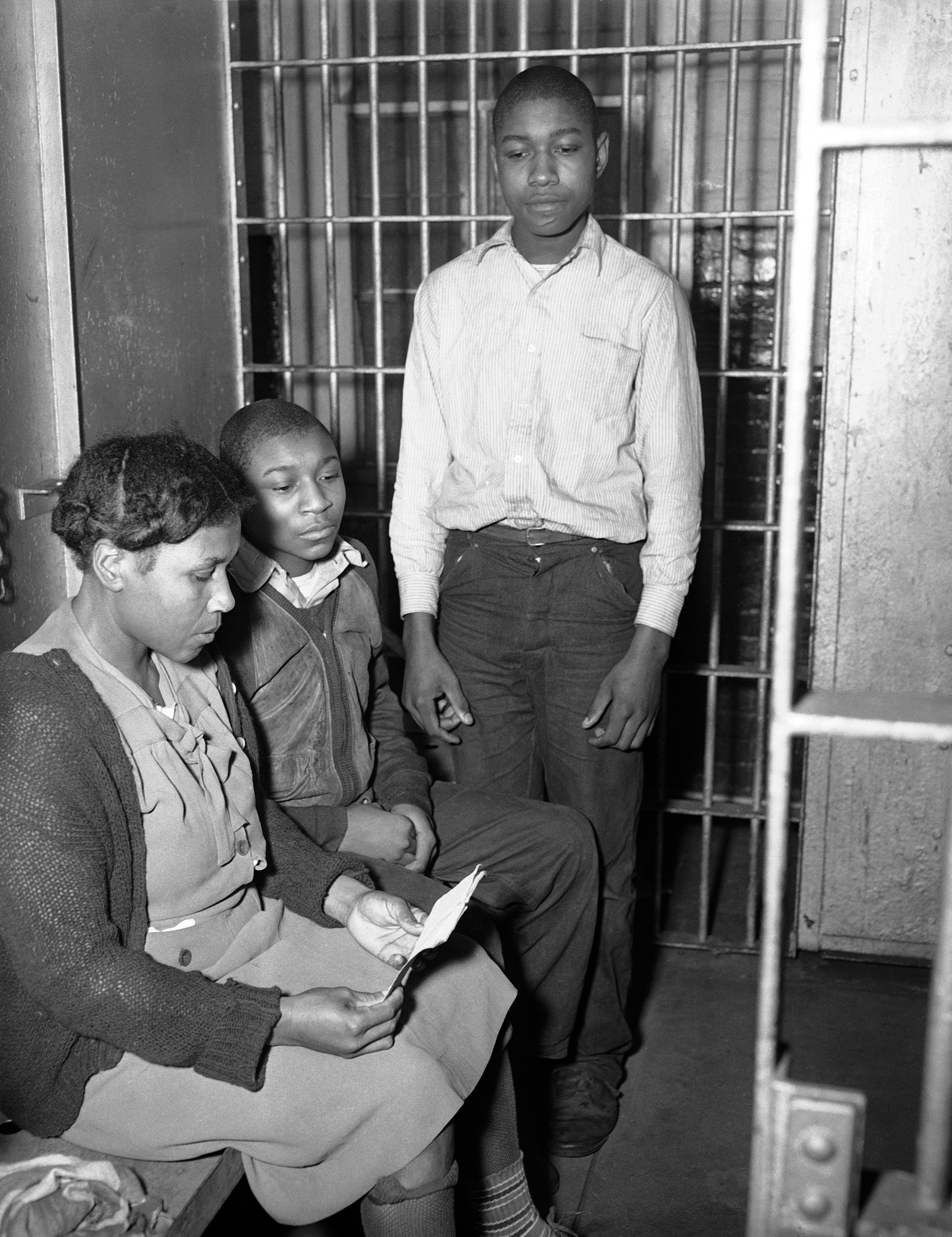

At that moment, her teenage sons, including 17-year-old Wallace and 14-year-old Sammie Lee, came to defend their mother with farm instruments.

Stratford later died due to blows to his head, according to an investigation. The widowed mother and her sons were subsequently charged with murder, while later testimony showed that Stratford threatened Ingram with sexual assault before striking her.

“An investigation of the murder ensued, but in the Jim Crow South, odds were not in favor of Ingram and the sons,” writes blackamericaweb.com.

On this day in 1948, Ingram and her sons – Wallace and Sammie Lee – were sentenced to death in a one-day trial by an all-white jury. It is said that one of Ingram’s sons, Charles, who was also at the scene of the 1947 incident, was acquitted in a separate trial due to lack of evidence.

Maintaining that she had acted in self-defense, Ingram, during the trial, said that “Stratford threatened her with a knife and struck her with a rifle. She then managed to take possession of the gun and struck Stratford about the head in self-defense.”

“She testified that Wallace also struck Stratford once with the rifle, but that none of her other sons had done the same. Wallace and Sammie Lee gave similar accounts on the stand. There were no other eyewitnesses,” writes New Georgia Encyclopedia.

The murder conviction of the Ingrams sparked protests, considering this was a period when the southern justice system and Jim Crow were being scrutinized.

Ingram’s case received national press attention while civil rights organisations launched an ambitious campaign to free her and her sons.

Members of the Atlanta chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) appealed the verdict, providing support to a local white lawyer appointed to the case, S. Hawkins Dykes.

Civil Rights Congress (CRC), a left-based organization, also joined in the campaign to get the Ingrams freed.

“The case marked the first occasion that the CRC, a relatively new organization, launched a national campaign to free a black defendant. The group never represented the Ingrams in court and at times disagreed with the NAACP’s strategy, but it played a significant role in bringing public opinion to the Ingram family’s side,” according to New Georgia Encyclopedia.

When the Ingrams appealed in 1948, Georgia courts reduced the death sentences to life imprisonment but did not take any further action, such as giving the Ingrams a new trial as requested by their defense attorney.

The NAACP and the CRC did not end there; they continued with their campaigns to free Ingram and her sons.

Women activists and organizations, including the National Committee to Free the Ingram Family and the Sojourners for Truth and Justice, later stepped in.

Working across class and color lines, these women groups worked assiduously to keep Ingram’s case alive in the minds of the public and the press into the 1950s. The Sojourners for Truth and Justice even called on then-President Harry Truman to intervene.

Finally, the Ingrams were released on parole in 1959 after having been judged to be “model prisoners.”

As Prison Culture noted, their release would also not have been possible “if not for the consistent agitation and organizing on their behalf by thousands of people across the world, and particularly Black women. It was that organizing that saved their lives.”