“…You can’t play politics with a weather bureau.

“If you make it political, people will die,” those were the words of Kerry Emanuel, a professor of atmospheric science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

He had, in 2017, given reasons for what he believed had caused The Galveston Hurricane of 1900, the deadliest natural disaster in America’s history.

Citing poor communication from U.S. weather officials and their lack of cooperation with the much-advanced forecasting system of hurricane-prone Cuba, the horrific hurricane wreaked havoc to the then thriving commercial city of Galveston, Texas, killing about 12,000 people, according to records.

Then perched on a low-lying barrier island between the Gulf of Mexico and the Texas mainland, Galveston was an “economic boom-town” and a major port with over 40,000 inhabitants.

“End-of-summer tourists flocked to the wide beaches with sweeping vistas of the Gulf of Mexico,” according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association.

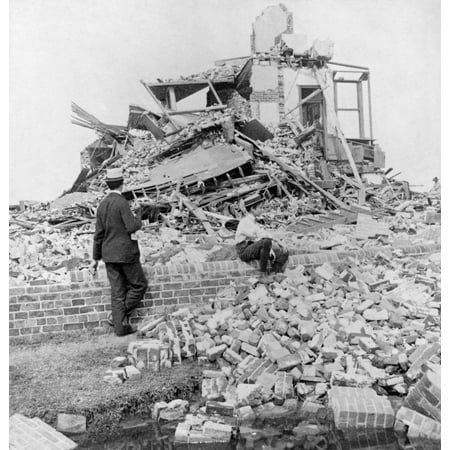

However, on September 8, 1900, a category four hurricane smacked the city, destroying more than 3,600 buildings with winds surpassing 135 miles per hour.

The scale of devastation could have been reduced if the U.S. Weather Bureau had not been poor with its communication policies, officials say.

The U.S. Weather Bureau, then only 10 years old, was not advanced in hurricane science, yet, moments before the disaster, it failed to communicate with Cuban weather officials, who “knew that a hurricane had passed to the north of Cuba and was headed to the Gulf of Mexico,” Emanuel was quoted by History.com.

To the Weather Bureau in Washington, the storm would pass over Florida and up to New England, a prediction which was “just way off target.”

Willis Moore, who was the bureau’s director, was reported to be “so jealous of the Cubans that he shut off the flow of data from Cuba to the U.S.”

He had also told regional forecasters in the U.S. that they could not issue a hurricane warning on their own without going through Washington. In those days, this was a laborious task for the regional forecasters.

Thus, even when Isaac Cline, the Weather Bureau’s head in Galveston suspected a few days to the storm that there was something amiss with Washington’s forecast, he could not warn the city on time.

In the end, an estimated 6,000 to 12,000 people lost their lives in the storm that destroyed Galveston. Even though the city was rebuilt, it never reestablished itself as the major port of call.

But the tragedy caused the U.S. Weather Bureau to sit up; in the following years, it opened up communication channels both within and internationally, including sending more wireless messages out to the sea.

Today, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association, the U.S. better detects, predicts, and issues warnings for dangerous storms and hurricanes.

Its only problem may be with logistics which make it difficult for authorities to do mass evacuations in the event of a natural disaster. For instance, in August 2017 when Hurricane Harvey devastated Houston and Galveston, it was well-predicted and communicated.

Residents, however, still suffered because authorities were not able to evacuate people as quickly and effectively as possible.