As I stared at the volume of bags with apprehension and admiration, I noticed that the leather was supple and the burnt orange and forest green fibers had a classic yet “exotic” nature to them. I thought to myself, These bags are beautiful but how in the world am I going to fit them all in my suitcase?! I pushed and tugged and laid across the top of the bag as I often do while trying to fit entirely too much in my suitcase, and finally, all 15 BuYu collection pieces made their way in to my luggage and were one step closer to their final destination: a luxury boutique in Lagos.

SEE ALSO: Look of the Week: Ajak Deng

I accepted this duty on behalf of my good friend Jeffrey Kimathi (pictured above), creator of popular Kenyan streetwear brand Jamhuri Wear and mastermind of BuYu, a luxury collection of luggage and travel accessories made of fine leather and woven fibers of the baobab tree.

Kimathi, as he is often simply called, gave me my first cosmopolitan African experience on the rooftop of an Indian restaurant in Nairobi. I was living in Mexico City then, and he insisted that we have a Patron toast over his city’s skyline.

I owed him at least one smuggling job for that.

Born in Nairobi, Kimathi rose to fame after paying his dues in N.Y.C. in the fashion house of Mark Ecko. Starting as an intern who wasn’t even enrolled in school, he left enough of an imprint at the label to be offered a marketing role with the brand.

It was there that he soaked up all he could about the industry and ventured out to create Jamhuri Wear’s first line in 2000. By 2003, Jamhuri’s star was beginning to rise, and he connected with Senegalese singer Akon who wore Jamhuri Wear in his “Ghetto” video.

Watch Akon wearing Jamhuri Wear here:

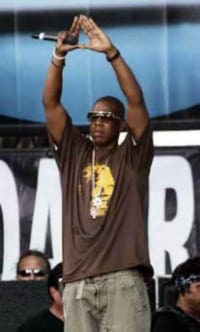

Then, Somali rapper K’Naan wore his designs, but his biggest break came in 2005, when celebrity stylist June Ambrose delivered a Mandela shirt from Jamhuri Wear to Jay-Z to wear at the Live 8 concert in Philadelphia (pictured below).

Back in the United States, after spending the past few years in Nairobi, I spoke to Kimathi about the business of African fashion and the multi-faceted nature of Africa’s creative class.

F2FAfrica: Describe the journey from Nairobi to the United States.

Jeffrey Kimathi: Growing up in Nairobi, there was limited opportunity for youth, which is still an issue today. Youth are the fountain of Africa, and they are not being fed. Norms of education and success were being forced on youth. Everyone was being sold the same version of success: “go work for Ernst & Young, be an engineer, be a doctor.” My whole thing was “either I create or I die.” My mom was a business woman; she left a big job in banking to become an art trader and won. She was elegant, taught me style and what art was, and even exposed me to Europe. I didn’t fit in there — mostly due to the language of Paris — so I moved to America.

I had always been exposed to positive images of America through shows like “The Fresh Prince of Bel Air” and artists like Tupac. For me, it was a chance to see that people who were Black like me could make it with their own dreams and visions of themselves.

I realized that I had to tell that story for Africa and felt like we had something powerful to share with the world. During my four years at Ecko, I began selling clothes online to the Kenyan diaspora and going to marathons. It was a real grassroots effort, where I was sort of running the entire African event circuit. There is an old saying that really encompasses it all, “Until the lion learns to speak, the tales of hunting will be weak.”

F2FAfrica: So why the move back to Nairobi?

JK: After the success of Jamhuri Wear and the whole Jay-Z fame, I was beginning to be “that guy,” so to speak. At the same time, I was facing some conflicts both within myself and for the brand. I would walk in to boutiques and they would say, “Who’s going to buy this? Africans don’t even wear clothes” — and that was the perception.

Eventually I did move in to retail heavy. We were sold out online at Dr. Jay’s, and then the challenge became, “Are you authentic?” People began to ask when was the last time I was in Africa. We were talking about this huge market, and people were asking me, “How do you know, when were you there?”

I was in talks with H&M about a deal, and it went south. Their response was, “You’re an African American now.” I didn’t fit their idea of the African designer story. I had lost my African “street cred,” so to speak, and I also needed new inspiration. I had an idea of Africa. I built a utopia of Africa for myself, but it was far from the real thing.

At the same time, Africa started replying to its own roar bringing out their own musicians like Dbanj of Nigeria. Jay-Z had gone to Tanzania wearing Jamhuri Wear, and Dead Prez had gone to Kenya rocking Jamhuri Wear the entire tour. I went deeper in to myself, and I needed to understand how this brand impacts the people of Africa: How do I use this to change economies?

The entire idea of my brand was about the republic [Jamhuri is swahili for Republic and marks the date of Kenya’s establishment] and not about me being the guy that dressed Jay-Z. So I traveled back, initially for 3 weeks, and then I ended up being there for 3 years.

F2FAfrica: What did you learn about Africa when you returned?

JK: When I arrived, MTV Base had just opened in South Africa. I went back home and reconnected and found that the Africa I had thought about for 12 years didn’t exist. I had to immerse myself in something brand new. Africa marches to its own beat.

F2FAfrica: Did your brand change once your were back on the ground?

JK: From seeing Africa with new eyes, I began to see possibility for home-grown innovation beyond the street wear scene. I found a new fabric that no one else was using. I was in a village and found women making bags out of the fibers of the Baobab tree, and I thought to myself, Maybe we can make luggage from this and offer this to the broader world.

Africa is the cradle of humanity and my journey back taught me that, but it’s the dignity that has been lost from the land. My goal has always been to reignite that dignity through great craftsmanship and ethical work, and that’s why Buyu (pictured above) was born. From the hardworking hands of these women to the quality natural materials, we will be able to uplift not only the small villages but the cities and overall build better people.

F2FAfrica: What are your observations about African designers now?

JK: I think it’s a scary place in the sense that the idea of fashion for many is still just the shows. There isn’t a lot of emotion in fashion from Africa. When Ankara started blowing up, it started with the great artist Yinka Shonibare who had emotion. Then Boxing Kittens started doing it, and then Beyonce wore it (pictured below), and then everyone started wanting to be an Ankara designer but we still didn’t own it — the fabric came from Holland.

It’s easier to just follow the system, but you’ll never make your name. Structure is the major issue holding back African designers and leaving room for others to take the ideas. Who is ready to fund that industry? Currently there aren’t enough early adopters ready to do the work. There aren’t enough people willing to build the structure.

I am ready though.

I am ready to see Las Vegas style trade shows like Magic for African fashion.

F2FAfrica: Is fashion the end game for you?

JK: Ultimately I’m a business man. Right now I’m trying to get Africans in the business of telling their own stories through creative ventures. You are selling a lifestyle and a story — not the products. People don’t buy Louis Vuitton bags; they buy in to the lifestyle it represents. We forgot that we created stories, and now we are injecting power back in to that.

We are the original traders and businessmen; we are now operating through that new power and understanding how to own that because that is business. We don’t own the business of marathon runners, we don’t own the business of the Masai, we don’t have good people telling us how to value our businesses and ourselves, but we are getting there.

My brothers and sisters in Nigeria are “getting it”; they are adding a level of sophistication to commerce that’s been missing, and I’m excited for that. I’m excited for us to realize our own stories, revolutionize the textile industry, build the infrastructure to support it — I’ll be a part of that. I’m interested in us creating a culture of ownership that allows us to play in the global market.

SEE ALSO: MIT Africa Innovate Conference 2014

Cherae Robinson is a self-described “passport stamp collector” and has traveled to nearly 30 countries, 8 of them on the African continent. In 2012 she realized one of her biggest dreams when she took 80 young professionals to Africa and founded the Afripolitans, a collective of professionals interested in creating a stronger narrative on Africa through commerce, connections, and creativity. Committed to being a “Game-Changer” in how the world sees Africa, Ms. Robinson’s vision has revealed itself in the creation of her first independent venture Rare Customs, a tourism market development firm.